Is Mekong River set to become the new South China Sea for regional disputes?

The Beijing-led Lancang-Mekong Cooperation mechanism was set up to help ease tensions over development projects, but environmental groups are yet to be convinced

Foreign ministers from the six countries through which the Mekong flows met in southwestern China last month to approve a draft of a five-year development plan for the river. But as state leaders prepare to finalise the proposal at a meeting in Cambodia later this month, environmental groups have expressed concern over what it could mean for Southeast Asia’s longest waterway.

Speaking at the end of the latest Lancang-Mekong Cooperation meeting in Dali, Yunnan province, China’s Foreign Minister Wang Yi said that the Beijing-led body had the potential to boost economic development in all six Mekong nations, and that China had made provision to help finance dozens of projects along its route.

He was joined at a press conference by Prak Sokhonn, the foreign minister of Cambodia – one of China’s biggest supporters within Asean – who thanked Beijing for its leading role in the LMC and described the progress it had made as “unprecedented”.

Wang did not engage in any public discussion of the various environmental concerns linked to the river’s development.

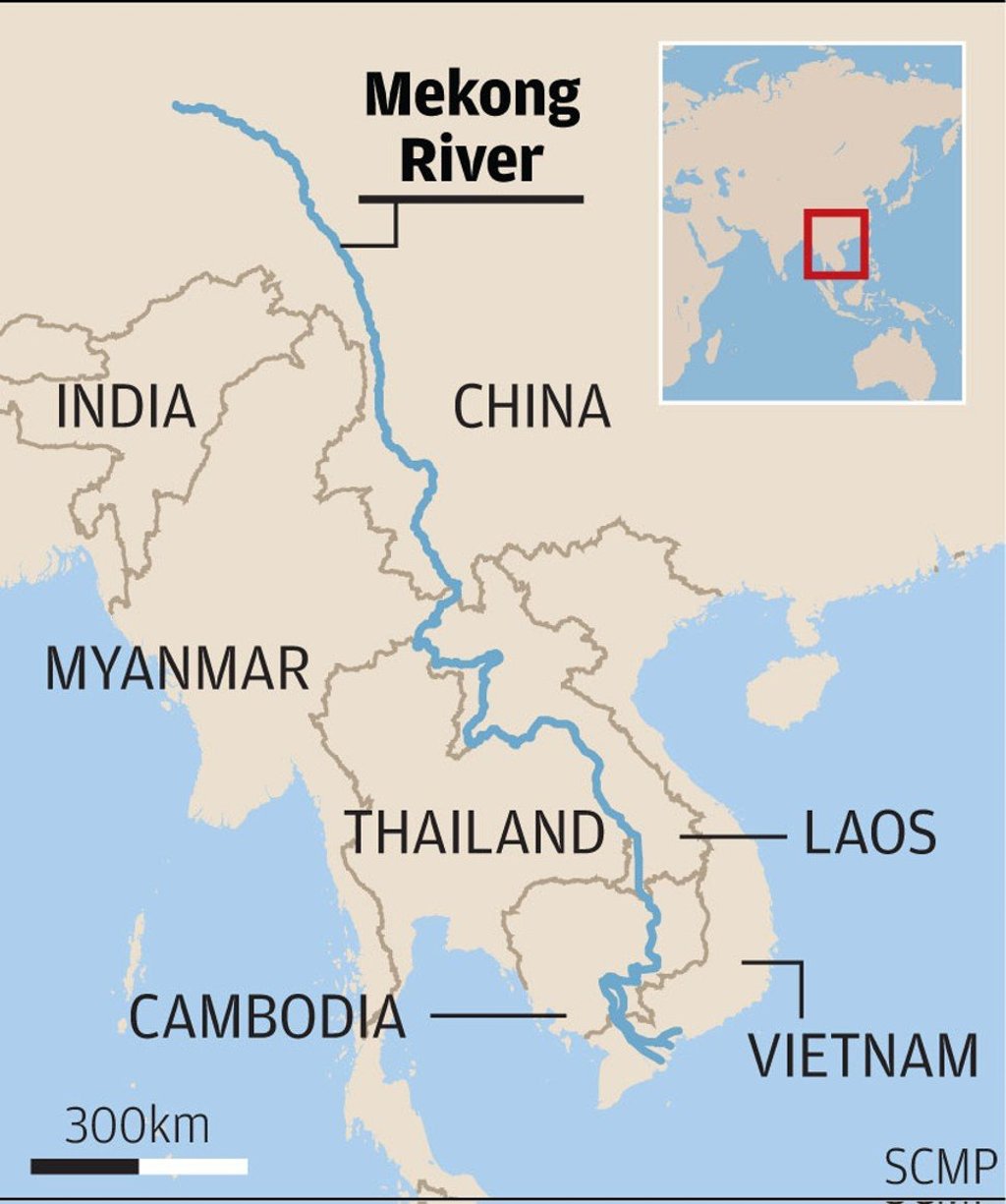

From its origins in the snowfields of Tibet, the Mekong – known as Lancang in Mandarin – passes through Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam – all five of which are members of the LMC and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations – before draining into the South China Sea.