The rise of the Little Pink: China’s angry young digital warriors

Who are these angry Chinese dominating the internet with their jingoistic rage, where are they from and how did they emerge? We tell you

Days earlier, Chinese actress Xu Dabao turned heads on the red carpet at the Cannes Film Festival in a bright red dress featuring the five stars of the national flag. The dress prompted accusations that she had desecrated the flag.

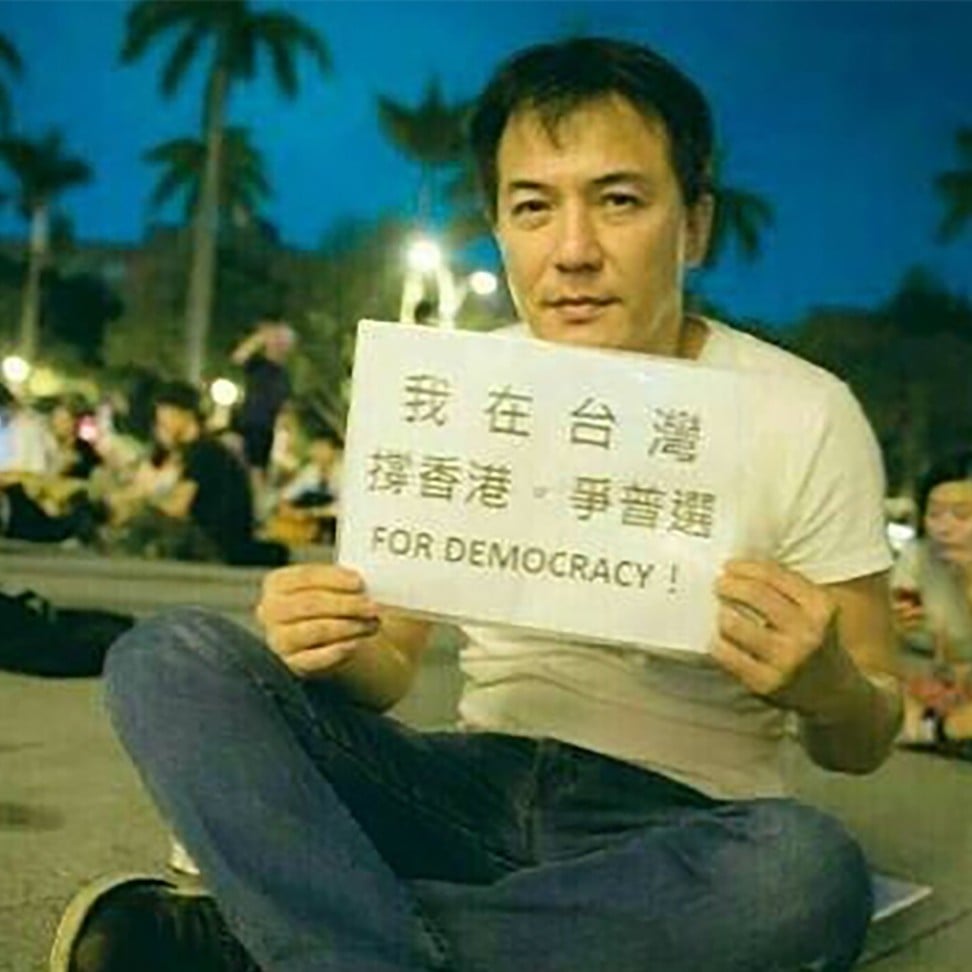

The two cases this week have highlighted the growth of nationalism on the mainland, particularly among the young. Young people fired with patriotic zeal are known in China as the “Little Pink”, as “xiaofenhong” in Chinese. Along with the “50 cent gang” – internet commentators paid to sing the praises of the government – the Little Pink are regularly seen online trying to guard China against even the remotest hint of criticism.

Who are the Little Pink and where are they from?

Contrary to perceptions that most online patriots are angry young men, the Little Pink are mainly female. Some 83 per cent of these keyboard warriors identify as female, according to a Weibo analytics tool developed by Peking University. Research published by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences says the Little Pink are predominantly young women aged between 18 and 24.

These young women reside both in China and abroad, with more than half of them living in smaller third- or fourth-tier cities on the mainland. Their social media accounts show their interests also include travel, music, celebrities and funny news.

When did they emerge and why are they called the Little Pink?

The term originated on the popular female-led literature website, Jinjiang Literary City, where users share original writing. Discussions expanded from writing and literature to politics and current affairs in about 2008 after there were riots in Lhasa and Urumqi before and after Beijing hosted the summer Olympics.

A group of the website users, some of them overseas students, strongly criticised people who published posts on negative news about China or comments deemed to glorify Western countries. They were called the Jinjiang Girl Group Concerned for the Country, or the Little Pink, a reference to the main colour on the front page of the website. The use of the term spread as social media expanded in China.

How did the Little Pink rise to prominence?

Mainland internet users flooded Chou’s Instagram account and accused her of supporting Taiwan independence. Days later, they flooded the Facebook page of the newly-elected Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen, who heads the independence-leaning Democratic Progressive Party. Some Taiwanese media outlets were also targeted.

What issues have offended the Little Pink?

How does China’s state-run media view the Little Pink?

The People’s Daily and the Global Times, controlled by the Communist Party, have sung the praises of young online nationalists. The Communist Youth League of China has also lauded their actions.

One commentary in the People’s Daily said: “Those who were born in the 1990s, we trust you. China is embracing the new generation, who stride with confidence and act freely and without restraints. They have made an impression with sunshine and confidence.”

Are the Little Pink organised by state authorities?

Although the Little Pink are generally known to be voluntary young internet users who genuinely believe they have the duty to defend China against outside criticism, there have been suspicions raised that they might be organised by state authorities.

However, there has been no evidence so far to suggest they are being directed by any government agency. Their online behaviour, though, has been publicly applauded by the authorities, including the Communist Youth League.