Booming Hong Kong trade in cancer drugs to buyers from the mainland

The under-the-counter sale of cancer drugs to mainland buyers is big business for some Hong Kong pharmacies willing to break the law

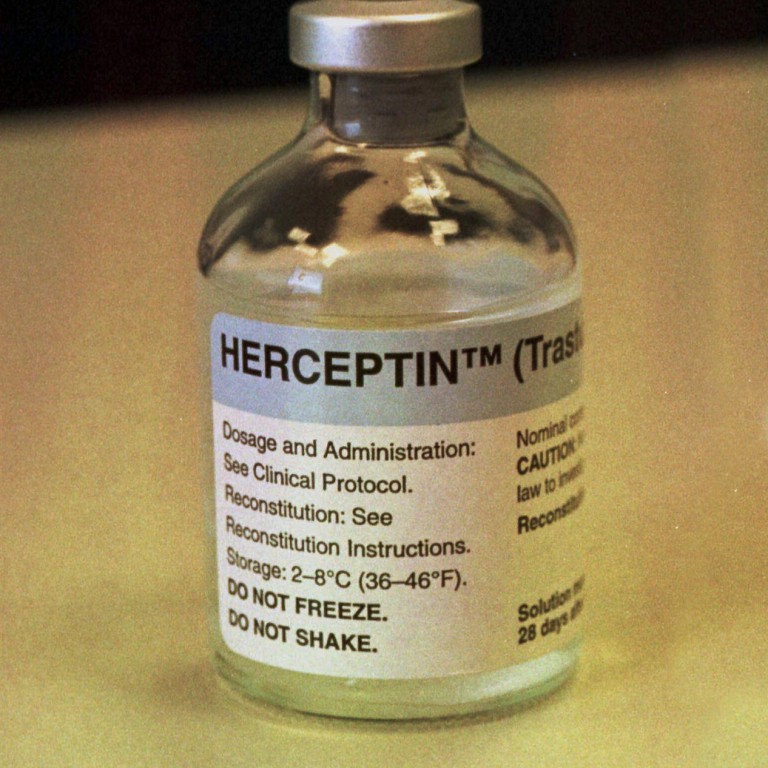

One shopper at a Mong Kok pharmacy says he has travelled from the mainland city of Guangzhou to buy the breast cancer treatment Herceptin.

He had obtained the drugs illegally, without a prescription, part of an illicit trade in cancer drugs that is thriving in Hong Kong thanks to pharmacies willing to break the law. One expert estimates that 90 per cent of cancer drugs sold in Hong Kong pharmacies are bought by mainland buyers.

Hong Kong pharmacies sell the drugs under the counter to mainland visitors who have lost faith in their own medical system and are dodging steep prices, as well as fears over tainted medicines. Patients are increasingly worried about the purity and safety of drugs dispensed on the mainland after several deadly medicine and food scandals.

Cancer treatments "are more toxic", says Tse Hung-hing, president of the Hong Kong Medical Association. "It is not like you are buying Panadol", the pain reliever.

People convicted of buying or selling anti-cancer drugs without prescriptions can draw maximum fines of HK$100,000 and two years' imprisonment, according to the Department of Health. Last year there were 24 cases of illegal prescription medicine sales leading to convictions.

I will save more than 8,000 yuan [HK$10,113] per bottle if I buy Herceptin here

Pharmacies tend to buy their cancer drugs from private doctors as a safer route than getting them directly from drugs companies, because direct orders are likely to be more closely monitored by the authorities, says Chui Chun-ming, the chairman of the Society of Hospital Pharmacists of Hong Kong.

Chui says 90 per cent of the cancer drugs sold in Hong Kong pharmacies are to mainland buyers, calculating that most local residents obtain medicines from hospitals or their doctors.

Mainland customers buying cancer medications without the required prescription is "very common", he says. "This illegal trade brings them [pharmacies] a lot of money," he says, referring to the city's small independent businesses.

Professionalism is an issue. The majority of community pharmacies in Hong Kong are owned by businessmen rather than professional pharmacists, he says.

The Hong Kong branch of Roche, which manufactures Herceptin, says it had been "made aware" of reports of mainland visitors buying oncology drugs in Hong Kong. "We are committed to supporting the relevant authorities with any investigations," the company said in a statement.

Despite the threat of prosecution, the trade continues. When a reporter visited four small independent pharmacies in Hong Kong and asked for 440 milligrams of Herceptin, each offered to sell it without a prescription.

Tse, of the medical association, says that the organisation had reported the problem to Hong Kong's Department of Health, but had not seen a significant response.

A health spokesman says the department has boosted surveillance in response to mainland drug demand.

Mainland patients have long worried about the safety of medicines produced in China. In recent years, authorities found that drug capsules had been made from toxic raw materials derived from scrap leather. There's also been a bustling business in counterfeit tablets.

In 2008 a widely used blood thinner called heparin, produced in China, was found to be contaminated. The bad pills were linked to 80 deaths and hundreds of allergic reactions in patients in the United States.

Fears about contamination are driving the new trade in Hong Kong. "People are not trusting their supply chains," says Ben Cavender, an associate principal at the Shanghai-based China Market Research Group. "They are worried that the drugs may be labelled incorrectly, or the quality is not that high, or the company decides to make it more cheaply in China than in the other countries, or they might be fake."

In a similar vein, mainland parents became distrustful of domestic milk brands after a huge 2008 scandal involving milk formula tainted with melamine. The toxic substance killed six children and sickened 300,000 others.

The fear over domestic food safety triggered a rush on milk powder, with parents emptying shelves worldwide. The surge prompted Hong Kong to bar travellers leaving the city from taking more than 1.8kg of formula with them.

Drug companies impose supply quotas based on factors including each country's population size. Considering that, Hong Kong could fall short of needed medicines if mainland demand continues, Chui, the pharmacists society chairman, says.

"The problem is Hong Kong is a very small city and the supply is very limited," he says. "In a few years, it might turn out to be another 'infant formula' issue."

According to a 2012 report released by the China National Cancer Registry, the country sees 3.12 million new cancer cases every year.

From 2006 to 2010, the number of cancer cases in Hong Kong rose at an average rate of 2.7 per cent each year, four times more than the annual population growth rate, a report by Hong Kong Cancer Registry showed.

Chui believes the increasing pressure on Hong Kong's cancer drug supply could soon reach crisis point.

"There is a high-probability that, in up to three years, the supply of anti-cancer drugs will become an issue," he says.