Prince Philip Dental Hospital used contaminated water, documents show

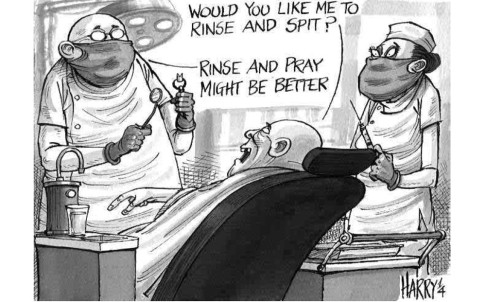

Hong Kong's dental teaching hospital may have given patients 'heavily contaminated' water to rinse their mouths, despite staff knowing it had been tainted with bacteria, the South China Morning Post can reveal.

Hong Kong's dental teaching hospital may have given patients "heavily contaminated" water to rinse their mouths, despite staff knowing it had been tainted with bacteria, the South China Morning Post can reveal.

It used the fouled water for four months this year, until it found a means of disinfection. Prince Philip Dental admitted to the that the contamination had occurred, but declined to specify bacteria levels or whether any patients had been affected.

Hospital chairman Sigmund Leung Sai-man promised a more detailed investigation.

"No patient has reported sick after oral treatment so far," Leung said. "It should be safe if patients did not swallow the water."

But microbiologist Dr Ho Pak-leung, of the University of Hong Kong, said people with weak immune systems were vulnerable to high levels of bacteria.

The papers showed that from mid-February to mid-June, water samples from the clinic exceeded 500 colony-forming bacterial units per millilitre - the US safe standard for drinking water.

The water was described as heavily contaminated, but bacteria levels were not specified. A hospital spokeswoman said the data "could not provide an accurate indication" as samples were not tested at an accredited lab.

A student had also found coliform bacteria - usually detected in human faeces - in the water supply when conducting research in April for a thesis, a source close to the hospital said.

The incident sparked calls to strengthen supervision of the independent hospital and to amend the law to cover staff misconduct.

Teaching staff who treat patients are not regulated or disciplined by the Dental Council.

"The council has no role in monitoring the hospital's operation," its chairman, Homer Tso Wei-kwok, said.

One report, marked confidential, said checks since mid-February had found "heavy biofilm contamination" inside tubing attached to dental chairs at clinic 3A. Biofilm is a phenomenon in which micro-organisms stick together on a surface.

Clinic 3A stopped using at least six chairs during a hospital attempt to improve water quality, the report said.

Staff were asked to avoid arranging treatment at the clinic for patients with cancer or cystic fibrosis, or those fitted with internal devices for assisted breathing.

The spokeswoman admitted "discoloured water was found in three dental units" and some common bacteria were identified. She said the fact that no one had reported falling ill indicated patients were safe, so there was no need to tell patients about the water discoloration.

Ho said it would be important to rule out the existence of pathogenic bacteria, such as ones that cause legionnaires' disease.

"The hospital should adhere to high standards and patients' rights should be protected," he said.

Dental hospital blasted for lax supervision after water contamination

The failure of Prince Philip Dental Hospital to disclose the contamination of its water supply highlighted the government's insufficient supervision, critics claimed yesterday.

Bacterial contamination was not made public until the exposed it, even though officials representing the Health Department and Food and Health Bureau sit on the hospital's board.

After it emerged that patients may have used contaminated water to rinse their mouths for four months, Tim Pang Hung-cheong, an advocate for patients' rights, and medical lawmaker Leung Ka-lau called for more transparency from the hospital, which is run by the University of Hong Kong's dentistry faculty.

Pang said the fact that no one was reported to have fallen sick as a result of the contamination did not mean no one had been made ill. "How can patients associate their sickness with the water problem when they are not informed?" he asked.

Central and Western district councillor Wong Kin-shing plans a survey to see if any patients were affected. "The hospital is popular among the elderly as treatment often costs less than HK$100," he said. "It shouldn't keep patients in the dark."

In the 2012-2013 financial year, 121,388 patients attended the hospital, while it got HK$130 million from the government.

The hospital is not supervised by the Health Department or the Hospital Authority. The Dental Council has jurisdiction over registered dentists but the faculty's full-time teachers are exempt from its scrutiny.

Even though the Health Department official who sits on the board had informed the department of the contamination issue, it did not alert the public.

A Health Department spokeswoman would not say why the department failed to inform patients of the incident. She said the hospital had taken measures to decontaminate its water lines.

In an internal email sent to staff in May, hospital comptroller Kenny Wong said it had not established any guidelines governing the disinfection of water lines connected to dental units.

An internal report on the chronology of the incident said the clinic had been too busy to disinfect them as frequently as it should have. "The clinic manager noted the fact that disinfection every two days [was] not feasible," the report said.

The chronology report said the manager ordered a 1:5 bleach solution to be used twice a week, "providing circumstances allow". But that solution did not work, and bacteria increased again a few days later.

A more effective solution manufactured in Finland finally solved the contamination problem. The report said it had required a month for delivery.

A hospital spokeswoman said the hospital had updated its infection-control protocols. The hospital did not share details of its decontamination practices prior to the incident.

According to the Prince Philip Dental Hospital Ordinance, the board of governors consists of 16 members, of whom 14 are appointed by the chief executive, including the chairman.

A spokeswoman for the Food and Health Bureau said it was represented on the board to ensure the hospital's operation was in line with government policies.

Dental Council chairman Dr Homer Tso Wei-kwok said the council could only investigate when a particular dentist was named. Such power is limited by the Dental Registration Ordinance, which exempts full-time teaching staff of the faculty - the only dental school in Hong Kong - from disciplinary control with open hearings. About 20 dentists in Hong Kong currently fall outside its jurisdiction, he said.

Tso said the law should be amended to cover teaching staff.

"The council was set up to protect people's health from substandard and incompetent practitioners. But why are some not subject to such control?"