The struggle for Hong Kong’s old and sick to die with dignity

A murder-suicide that highlighted the plight of elderly people struggling to cope with major health issues has led to renewed calls for the government to improve end-of-life care services

A few months ago, tragedy struck in a 15th-floor flat in Diamond Hill, where police discovered 58-year-old Au Kin-ming had jumped to his death after strangling his 56-year-old dementia-suffering wife, Fung Shuk-ying.

Au, who himself suffered from a skin condition, sent a heartbreaking text message to his siblings moments before the murder, confessing he felt “hopeless” because of his wife’s illness.

“The couple’s deaths should serve as a wake-up call for the authorities,” said Paul Yip Siu-fai, director of the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong.

“Services for the elderly are far from adequate. With its rapidly ageing population, Hong Kong must do better to meet the social, physical and psychological needs of its elderly folk.”

Recently in Taiwan, the end-of-life care debate was reignited after a doctor revealed on Facebook how he was forced to carry out cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) on a terminally ill 75-year-old cancer patient – despite the man previously telling him he would prefer an easy death. But the man’s sons disagreed, mostly because they did not want other relatives to blame them for letting their father die.

Do-not-resuscitate option

The doctor described how he was in tears during the CPR, feeling that the ribs and lungs of the patient were crushed during the emergency procedure.

He administrated CPR four times but the patient died. A few local doctors who shared the story said they had had similar experiences in Hong Kong as the city lacked a legally-binding cause allowing terminally ill patients to opt for a do-not-resuscitate option in the event their heart stopped.

The principle is founded on the notion of informed consent and the idea that humans should have the right to decide issues relating to their health care.

“Our number one priority is to allow seniors to have a dignified peaceful end-of-life experience; no pain, and little suffering,” said Gwen Kao Wong May-wan, one of the city’s leading advocates of the need for improved end-of-life care services.

Having spent over 30 years looking after her husband in the New Territories, she said the city’s legal and operational barriers had to be lifted in order to allow terminally ill people to spend their final days at home or in a palliative care unit, rather than in hospital.

But there had been limited progress in persuading officials to relax laws on “do not resuscitate” requests in cases involving terminally ill patients, she told the Post.

Life expectancy will get to 100 years ... Many will still be forced tube-fed for the last six or more months at the end of their lives

“I’m not too optimistic about this situation in Hong Kong. Life expectancy will get to 100 years and we will become frail. Many will still be forced tube-fed for the last six or more months at the end of their lives, lying comatose maybe and certainly in pain. Seniors at this stage should have the choice not to be kept alive at all costs.”

Kao went on to say that although her husband remained a “generally happy guy”, he could no longer speak.

“He is in the late stage of Alzheimer’s, but is otherwise quite fit, eats well, sleeps well. It is possible he has more cognition of what happens in his daily life, but with lack of language, we can only guess at the extent of understanding.”

Dying in a cosy bed at home rather than an overstretched hospital, also, is not an easy option in the city. Under current laws, this requires certification from a doctor, who must have seen the patient within two weeks before death.

This partly explains why in 2014, 90 per cent of 46,000 deaths in Hong Kong occurred in the city’s hospitals. In Taiwan, by comparison, 40 per cent of deaths were in hospitals that year, with an almost equal number at home.

Like much of Asia, Hong Kong faces growing problems as a result of its ageing population; by 2030, one in four Hong Kong residents are expected to be aged 65 or above.

The number of annual deaths in Hong Kong increased from 24,832 in 1981 to 46,108 in 2015, according to the Census and Statistics Department.

Also, dementia is one of the main degenerative conditions that is increasingly affecting elderly Hongkongers; experts have predicted the dementia population could triple from 100,000 sufferers in 2015 to 300,000 in 2039.

But there were estimated to be just 19 palliative care specialists in the city as of last year. Public hospitals under the Hospital Authority offer only 360 palliative care beds.

The money will fund 149 extra subsidised places for elderly residential care and day care places, improve end-of-life services for nursing homes, and increase manpower in caring for those with dementia.

Age-friendly environment

Paul Yip has called on the government and its partners to work hard to create a more “age-friendly environment” in which long-term care services, palliative care and day-care units in homes were more available.

“Depression is a major factor contributing to a loss of meaning in life and the development of suicidal thoughts among older adults,” he said. “Other factors include poor physical health, substandard living arrangements, a lack of social support and an inability to take care of themselves.

“The problem could be compounded if the duty of care falls on an elderly life partner who also needs help.”

Former health minister Yeoh Eng-kiong is due to submit recommendations to Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor’s government on elderly care within about two weeks.

He told the Post this week he was confident the government was committed to making reforms on elderly care, but he said it was too early to say what or when changes to the system might be introduced, or exactly how much they would cost.

“There are quite a lot of issues,” he said. “It is not just about the law. It is about the culture; the whole infrastructure needs to be there. You need support for people to die at home; hospitals are not very good places because they are still quite overcrowded.”

“In Hong Kong, there may be occasional cases of terminally ill patients requesting euthanasia when their physical and mental pain goes unmanaged,” former health minister Dr Ko Wing-man said last year.

“However, most of these patients will change their mind and give up their requests when their pain is under control after receiving suitable palliative care treatment. We should therefore look for ways to improve our palliative care services for terminally ill patients, instead of considering how to implement so-called euthanasia.”

The Hospital Authority does not compile statistics on the number of Hongkongers seeking euthanasia and there remains no comprehensive study on how many people would support legalising it.

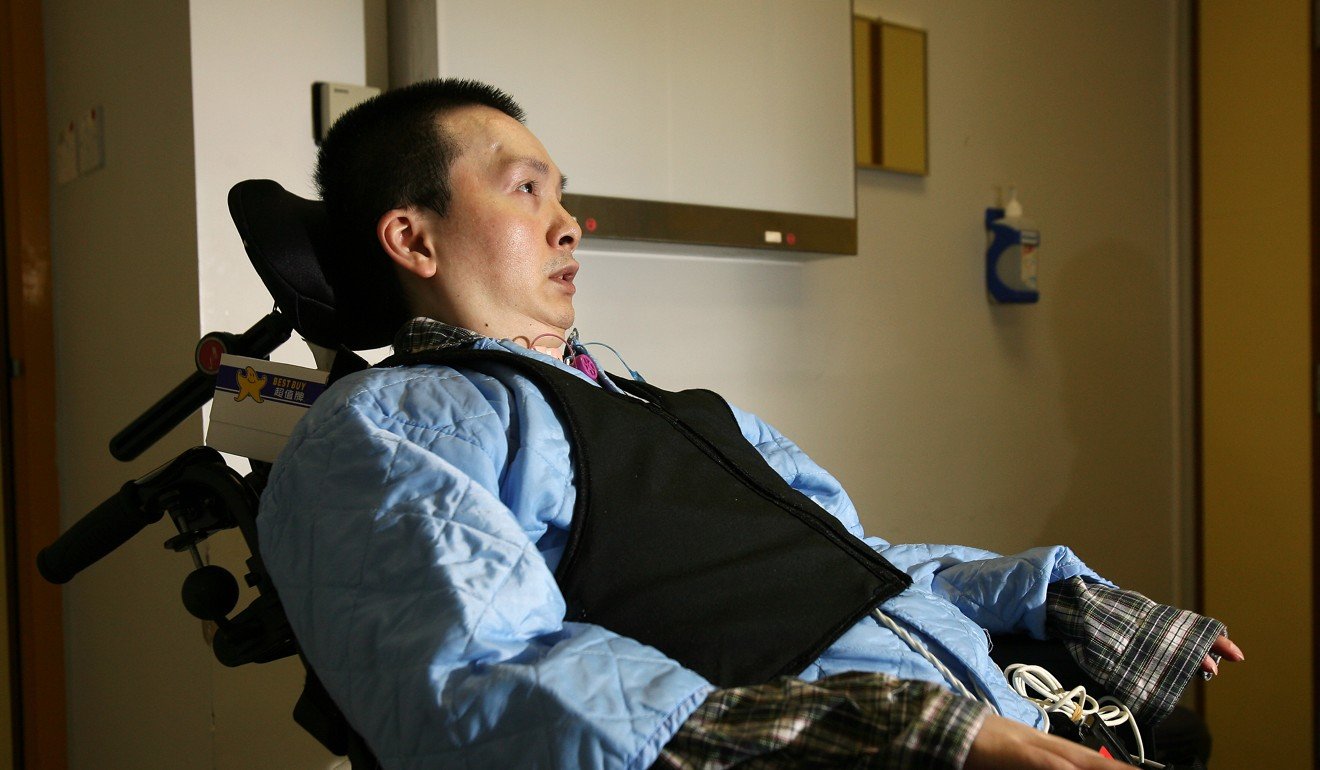

Tang Siu-pun, who died in 2012 aged 43, remains Hong Kong’s most high-profile euthanasia proponent. Affectionately known as Ah Bun, he once typed a letter by holding a chopstick in his mouth to Hong Kong’s then chief executive Tung Chee-hwa, asking for euthanasia to be legalised so he could die.

His request was rejected but he maintained he still supported euthanasia in principle.

EASING THE PAIN

What is an “ advance directive” (AD)?

It is a statement written and signed by a mentally competent person indicating the form of health care he or she would like to have when no longer mentally capable of sound decision making, or having consultations with a doctor. Advance directives include a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order in the case of a patient’s heart stopping. Euthanasia is not equivalent to an advance directive.

What is Hong Kong’s stance on ADs?

The ageing population has caused the city to concern itself more with issues of elderly provision, especially the treatment of terminally ill elderly persons or those with dementia. The topic of signing advance directives is thus growing in significance. There is no one official format for advance directives, but the Hospital Authority has its own list of criteria and forms for people to consider.

What are the legal implications?

Hong Kong has no legislation or case law covering the legal status of signed advance directives. Moreover, it was highlighted in 2015 by The Economist that a DNR order has no legal standing in Hong Kong. But such directives have been held to be legally binding at common law in other jurisdictions, and are recognised in Hong Kong as valid unless challenged.

What human rights debate surrounds the use of an advance directive?

Proponents of advance directives typically believe it is within a person’s autonomy to make informed health care decisions on their own well-being. On top of that, supporters fear that developing technology will lead to the prolonging of life, without care for the dignity or quality of the patient’s existence. The misconception that the directives are equivalent to assisted death or euthanasia has also spurred greater debate.