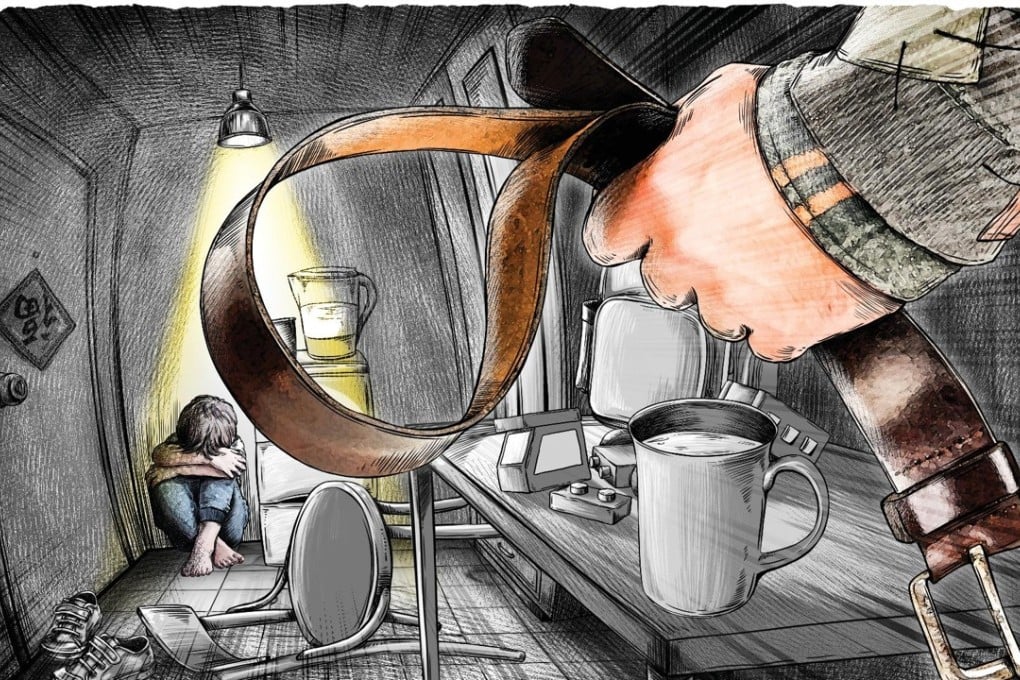

In Hong Kong, most child abuse victims suffer at hands of parents

A recent spate of child abuse cases has cast the spotlight on the factors that cause adults, especially parents, to hurt minors in their care. But beyond getting tough on abusers, early intervention by teachers and social workers is key to preventing tragedy, experts say

It is a sunny Sunday afternoon at the Sai Ching Street Children’s Playground in Yuen Long.

From a distance, giggles and squeals can be heard as wide-eyed children whizz down the slide or challenge each other to see who can go higher on the swings.

Close by are their parents and grandparents keeping a watchful eye to make sure fun is had by all without anyone getting injured.

But the life of children in Yuen Long is not always this blissful. The district – one of 18 residential areas in Hong Kong – consistently has the highest number of child abuse cases in the city.

Latest available full year figures from 2016 showed that 12 per cent – or 107 – of 892 incidents of abuse against children below the age of 18 took place in the New Territories district, followed by 102 in Kwun Tong, 85 in Tuen Mun and 77 in Kwai Tsing.

In contrast, there were 29 cases reported in Tsuen Wan and 8 cases in Wan Chai.