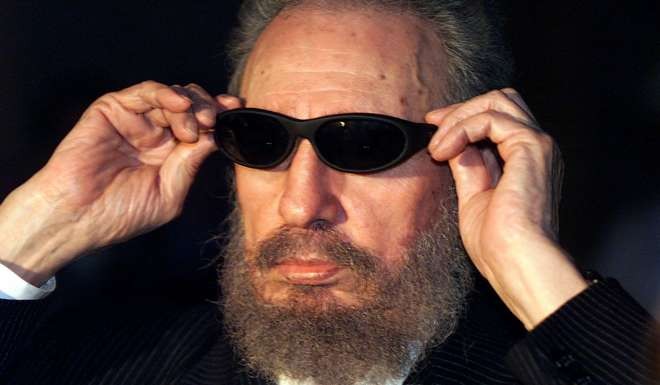

A country molded by Castro wonders what comes next

They woke up Saturday and found out he was gone.

A numbness has set in here since. Few Cubans seemed to believe the death of Castro at age 90 will bring immediate transformation of their country, the only one-party state in the Western Hemisphere. After all, poor health forced Castro aside in 2006, and the system he created has carried on without him.

Watch: A look back on the life of Fidel Castro

But Castro’s death nonetheless represents a psychological break with Cuba’s past and the figure who has dominated it for three generations. There is enormous, built-up pressure, especially among younger generations, for a faster pace of change that brings new freedoms and better living standards.

The question now is what human rights will look like in a future Cuba. The lives of many depend on it

Among the Cubans who want change to come faster, and who are tired of the political divisions and tensions that Castro represented, there was a hushed sense of relief at the news of his death.

“People here are so tired. He destroyed this place,” said a university engineering student who was walking home Saturday morning from the market in Havana’s central Vedado neighbourhood. He began trembling when a reporter told him that Castro had died, and that this time it wasn’t a mere rumour.

“I think you have to look at both the good and the bad, but there was more bad,” said the student, who declined to give his name, saying it would land him in trouble at school.

As reports of the Cuban leader’s death spread in the capital, there were no signs of unrest but, perhaps just as tellingly, not much spontaneous mourning either. Cubans went on with their lives in a world that is very much Castro’s creation: they went shopping at government stores, waited in government hospitals and tuned in to (or turned off) round-the-clock Castro tributes on government television.

However, in Miami, where many exiles from Castro’s government live, a large crowd waving Cuban flags cheered, danced and banged on pots and pans to celebrate the passing of a man they loathed.

“This isn’t like the death of Stalin, or Mao, when people threw themselves into the streets and thought the world was coming to an end,” said Aurelio Alonso, a sociologist and the deputy editor of the Cuban journal Casa de Las Americas. It was something they have been expecting.

“People are mourning, sure,” Alonso said, “but he had a long life.”

For years, foreigners speculated about whether the death of Castro would bring dramatic change. But Castro’s succession plans were completed years ago, leaving his noticeably healthier brother, Raúl, 85, fully in charge. Cuba’s military and security services remain firmly in control of the state and allow no organised opposition or public dissent.

Raúl Castro plans to step down in 2018, and vice president Miguel Diaz-Canel, 56, a career Communist Party official who is not related to the Castros, is in line to succeed him.

Cuba has mostly recovered from the post-Soviet austerity period that left Cubans hungry and desperate in the early 1990s, when riots broke out in Havana and Fidel Castro showed up to quell the crowds.

Fidel opened Cuba up to tourism, and a record 3.5 million visitors arrived last year, far more than the number who came here before his 1959 revolution shuttered the island’s casinos and led to the seizure of all the hotels. Those travellers include an increasing number of US visitors, providing a cash infusion at a moment when economic growth is otherwise stalled. The first commercial flight from the United States to Havana in more than a half-century is scheduled to land Monday.

Still, there is growing discontent with the system Castro created and declared “irrevocable.”

The socialist system affords Cubans access to health care, education and food rations but has failed for decades to provide them with more than the essentials. And the country’s economic outlook appears to be going from bad to worse.

With the death of Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez in 2013, Fidel Castro lost his political protege and Cuba’s main economic benefactor. Chávez sent billions of dollars in petroleum shipments, helping the government in Havana keep the lights on and the air conditioners running, with enough left over for Cuba to re-export the oil at a profit.

But oil prices have crashed, Venezuela is mired in crisis, and no other easy income source is coming to the Cuban government’s rescue. Cuba’s economic growth is once more stalled, and emigration is at a 10-year high.

Modest steps toward economic liberalisation undertaken by Raul Castro led to a boom in small businesses, especially restaurants and bed-and-breakfasts, but the opening has lost momentum. The government has kept American firms at arm’s length despite a surge of interest from US businesses after Obama’s normalisation moves.

In an April speech, the younger Castro quipped that Cuba was not actually a one-party state: “We have two parties here, just like in the United States,” he said. “Fidel’s and mine.”

Fidel’s is the Communist one, Raul added, “and you can call mine whatever you want”.

Critics found nothing to laugh at, but former Cuban diplomat Carlos Alzugaray said it wasn’t entirely a joke. Hard-liners within Cuba’s hermetic power circles identified more with Fidel than his younger brother.

Many of the liberalisation moves introduced by Raul Castro represent an implicit rejection of his older brother’s rigid, state-dominated economic model.

“Raul Castro will have a freer hand now,” Alzugaray said.

“It’s not that Fidel Castro would have opposed him,” he said.

“But it’s like when you have a sick relative and don’t want to upset them. There are things Raul probably didn’t want to do while his brother was still around.”

In the wake of the revolutionary’s death, human rights groups said they hoped that his brother and successor would move faster toward allowing Cubans more freedom of speech, assembly and other basic rights.

“The question now is what human rights will look like in a future Cuba,” Erika Guevara-Rosas, the Americas director for Amnesty International, said.

“The lives of many depend on it.”

Under Raul Castro, Cuba has moved away from jailing political prisoners for extended sentences, instead making thousands of short-term arrests each year that Cuban dissidents say are designed to harass them and disrupt any attempt at political organisations. Cubans today feel freer to criticise their government in public, but any attempt at protest or demonstration is swiftly quashed. Independent journalists operate inside the country but find it nearly impossible to distribute printed material and they report repeated harassment from authorities.

The government has declared a nine-day period of mourning, heavy with revolutionary symbolism.

Castro’s body will lay in state Monday and Tuesday in Havana’s Plaza of the Revolution, where Cubans will be able to “pay tribute and sign a solemn oath to fulfill the concept of Revolution,” according to a statement in the Communist Party daily Granma.

After a mass gathering in the plaza planned for Tuesday, Castro’s body will be carried to Santiago de Cuba, at the southeastern end of the island, reversing the journey that his bearded rebels made in January 1959 when they seized power.

On Saturday, police and soldiers sealed off access to Havana’s central plaza, where most of the headquarters of the Communist Party and government buildings are clustered. But there was no heavy security deployment visible in the city’s streets.

Castro’s death is “a huge loss for us,” said Jose Candia, 70, who woke up to the news and took his dachshund for a walk along Havana’s Malecón sea wall.

Candia and other older Cubans dedicated their lives to low-paying government jobs that demanded absolute loyalty and discipline. The news of his death seemed to hit them hardest.

“I think of his bravery. His honesty. I’ve been committed to him all my life,” said Yolanda Valdes, 75, a history teacher and Communist Party member. Tears began running down her face. She said that she had been crying all morning.

“I adored him,” she said.

Additional reporting by Reuters and Tribune News Service