Cooking with Asian leaves and herbs: a guide on the best ways to use them

Cookbook provides a reference and recipes for using Asian leaves, as well as advice on storing herbs and leafy greens and when it’s best to pick them

I am pretty familiar with most of the herbs and leafy greens available in Hong Kong wet markets but, when I visit the fresh produce shops in other Asian countries, I discover ingredients I’ve never seen before. This book, which I use more as a reference than as a cookbook (although it does contain recipes), is for those occasions.

In the introduction to Cooking with Asian Leaves (2004), Devagi Sanmugam and Christopher Tan write, “Leafy vegetables in particular seem to proliferate at vegetable stalls, in a wide array of leaf shapes and sizes, scents and textures. Many are traditionally used by a particular culture, outside of which they are barely known.

“This book is intended to shed some light on those attractive bunches of leaves you liked the look of this morning but didn’t recognise, or the bag of herbs you bought last week and couldn’t figure out a use for. It is not meant to be an exhaustive examination of every leaf on the market, but a practical guide to using some of the more common, and some of the slightly less common vegetables and herbs you may come across.”

The book gives useful advice on storing herbs and leafy greens, and even a little information on when it’s best to pick them, if you grow your own.

The selection is quite extensive. There are leafy greens that are easy to recognise for us in Hong Kong, such as chrysanthemum greens, chives, dill, shiso and watercress. But to source some of the other herbs and greens, you’ll have to search shops that specialise in Indian, Thai or Straits cuisines.

Turmeric leaves, for instance: I expected they would be orange-coloured, like the more familiar turmeric rhizome, but they are not; they are green, and, as the authors describe it, have “a very mild grassy taste, and a lemony scent that is light but enticing. It calls to mind the most volatile gingery, citrusy notes of the aroma of cut turmeric root.” They use it in dishes of fish lemak and sambal egg (both of which also use the rhizome).

And fenugreek: until reading this book, I’d only thought of the plant’s seeds, never the small, delicate leaves. The leaves, which have “refreshing nuances of celery, parsley, spinach and a distinct bitterness” are cooked into masala fish, and with spinach kootu.

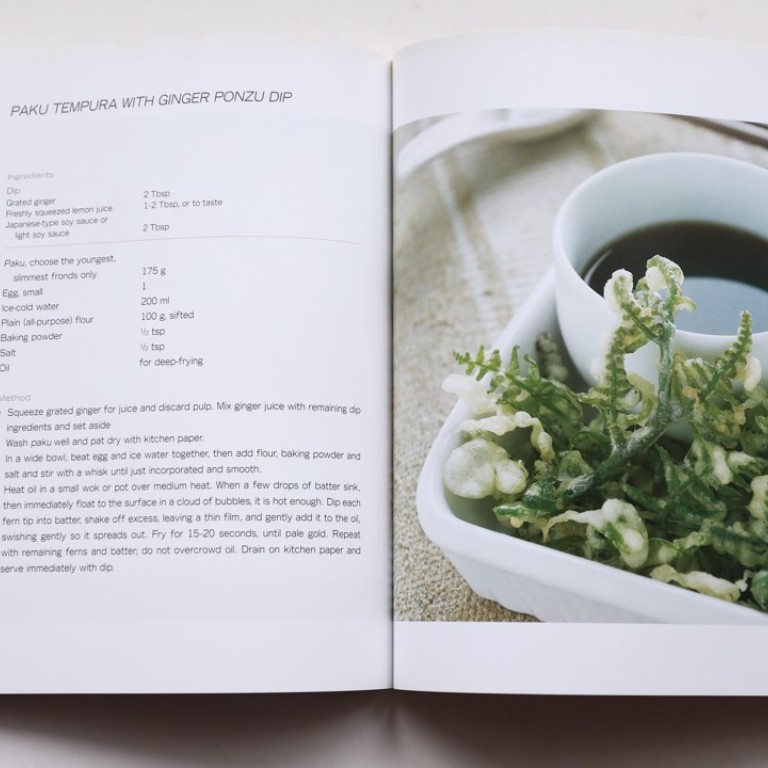

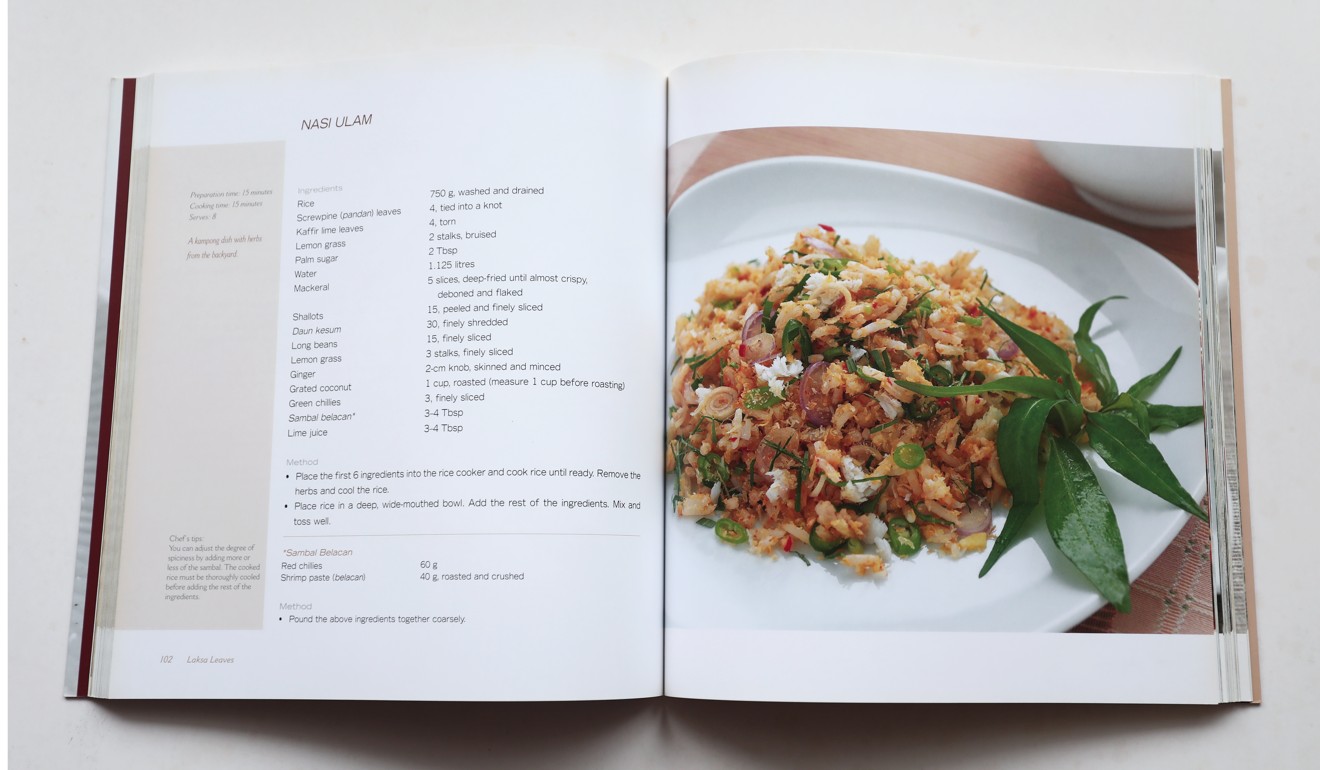

Other leaves they cover include kaffir lime (otak otak, sambal timun); laksa leaves (nasi ulam, assam fish head curry); paku (scrambled eggs with paku and garlic, paku tempura with ginger ponzu dip); rice paddy herb (Khmer steamed fish, Cambodian tamarind prawn soup); and sour spinach (gongura chutney, gongura chicken).