Sri Lanka’s Ranil Wickremesinghe is a schemer and the West’s stooge. Not the man to lead it out of crisis

- Ranil Wickremesinghe, a five-time PM who has never completed a full term in office, only gained the presidency via horse-trading and with Western help

- He claims he can schmooze the IMF, but Sri Lanka would be better served if India and China stepped up and worked with Russia to craft a BRICS bailout

The five-time prime minister – who has never completed a full term in office – is seen as a smart schemer and political survivor, not a unifying force. As a member of Colombo’s English-speaking elite, he’s more at ease connecting with Westerners than he is with the country’s grass roots.

The first was a regime change in January 2015, when Wickremesinghe began his third turn as prime minister and quickly moved to grab most of the executive powers from the office of the president. In the run-up to those polls, Western-funded NGOs had painted then-President Mahinda Rajapaksa as corrupt and a violator of human rights.

When he was last in power as prime minister, Wickremasinghe was accused of secretly negotiating with Washington for a US$500 million grant through its Millennium Challenge Corporation to create a land register, and for a status of forces agreement to make it easier for US troops to be based in or transit through Sri Lanka – both major factors behind his rejection by the electorate in 2020 and the national backlash that returned the Rajapaksas to power.

Wickremesinghe not only lost his own seat in those elections, but his United National Party (UNP) – the country’s oldest – was nearly wiped out, retaining just one seat in parliament.

Following that debacle and the 28 other elections – including provincial and local government polls – that the UNP had lost with Wickremesinghe as leader, the party asked him to step down. He promised that he would, but never actually relinquished the leadership of a party he has headed since 1994.

He quietly sneaked back into parliament last year through a national list seat that the UNP won for garnering more than 2 per cent of the national vote in 2020, a seat he had kept vacant for months. Sri Lanka’s parliament has 196 elected MPs and 29 nominated national list MPs, who are appointed by political parties or independent groups.

‘The usual horse-trading and bribery’

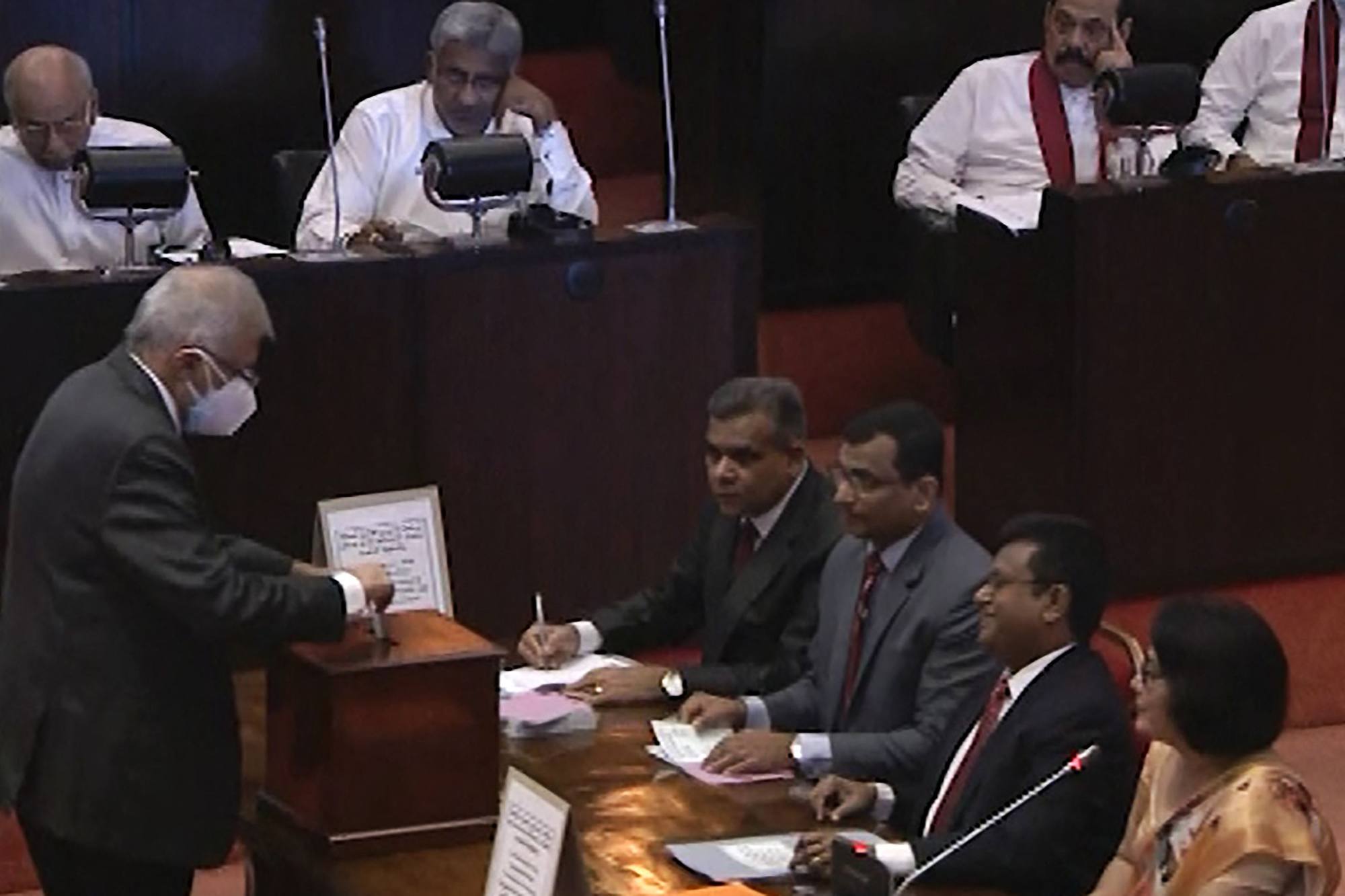

Speaking after Wednesday’s unprecedented vote by Sri Lanka’s 225-member parliament that made Wickremesinghe the country’s eighth president, Marxist–Leninist communist Janatha Vimukthi Peramuna party leader Anura Dissanayake called for an immediate general election to clean up the chamber of corrupt politicians – accusing most MPs of voting against their own party policy as a result of “the usual horse-trading and bribery”.

Dissanayake had also run for the top post but attracted just three votes to Wickremasinghe’s 134, with the new president’s main opponent Dullas Allahaperuma garnering 82. Allahaperuma was the candidate of the Rajapaksa’s Sri Lanka Freedom Alliance that has 145 seats in parliament and he was proposed by the leader of Samagi Jana Balawegaya, a UNP breakaway group that has 54 seats.

“The people on the ground are not reflected in the current parliament,” Dissanayake told MPs on Wednesday in a booming voice. “If anyone still believes that the people’s aspirations were fulfilled in parliament today, that is a myth. There is a huge gap between the people outside and those in the chamber.”

Dissanayake gave past examples of “MPs being traded from side to side” in 2015, 2018 and 2020 to support his assertion that Sri Lanka’s “MPs are sold like how teak trees are bid on in villages”. His call for an immediate general election to solve the issue is shared by the Aragalaya movement that brought down Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s presidency.

Outside the presidential offices in Colombo where about 200 Aragalaya protesters were still camped when the vote took place, the mood was sullen. “We lost – the whole country lost,” Damitha Abeyrathne, a prominent Sri Lankan actress and regular fixture at the protest site in recent months, told reporters. “The politicians are fighting for their power, they’re not fighting for the people. They have no feelings for the people who are suffering.”

The West, not China, bankrupt Sri Lanka

When Aragalaya started there was a lie spread around the world that Sri Lanka’s economic crisis was caused by a Chinese “debt trap” that was the result of the Rajapaksas’ close relationship with China. A close analysis shows it was, in fact, a Western debt trap that brought Sri Lanka to its knees and precipitated a regime change.

Only 10 per cent of Sri Lanka’s debts are owed to China, while 47 per cent are owed to mainly Western banks and financial agencies from which Colombo has had to borrow at high interest rates after those same agencies downgraded its credit rating. The country is a good example of how debts are being used for geopolitical battles.

Perhaps Sri Lanka needs Singaporean and Chinese experts to advise on how to run public companies efficiently and profitably

A narrative has built up both in the local and international media that Sri Lanka needs to go to the IMF because it will force economic discipline on the country, whereas the Chinese are happy to lend to “corrupt regimes” such as Rajapaksa’s.

Ironically, the privatisation of Sri Lanka’s lost-making public companies is believed to have been one of the recommendations made by an IMF team that visited the country last month to make an assessment. Perhaps Sri Lanka instead needs Singaporean and Chinese experts to advise on how to run public companies efficiently and profitably.

Dr Kalinga Seneviratne is a Sri Lanka born journalist, media analyst and international communication specialist currently based in Sydney.