Key rates are poised to rise in the first quarter, but what does this mean for Hong Kong borrowers?

Hibor is rising but analysts do not expect banks to raise prime rates until 2018

Interest rates in Hong Kong are rising for the first time since they were slashed following the global financial crisis. The benchmark Hong Kong interbank offered rate (Hibor) hit nine-year highs last week, and analysts expect commercial banks will change their prime rates for the first time since 2008 in the first quarter next year.

Over the past two years, Hong Kong government officials have issued warnings about the potential risks of higher interest rates for homeowners and companies.

Banks kept their best lending rates absolutely flat and Hibor, a benchmark, remained at low levels even though the Hong Kong Monetary Authority, the city’s de facto central bank, has raised interest rates four times since December 2015, following the US Federal Reserve. Now prime rates and Hibor are rising, and it remains to be seen whether the officials’ concerns were justified.

It is not bad news for everyone, however. Savers, long accustomed to anaemic rates of return on their savings, will see a slight pick up, and an increase in the cost of mortgages could see prices fall, making it easier for first-time buyers to get on to the housing ladder.

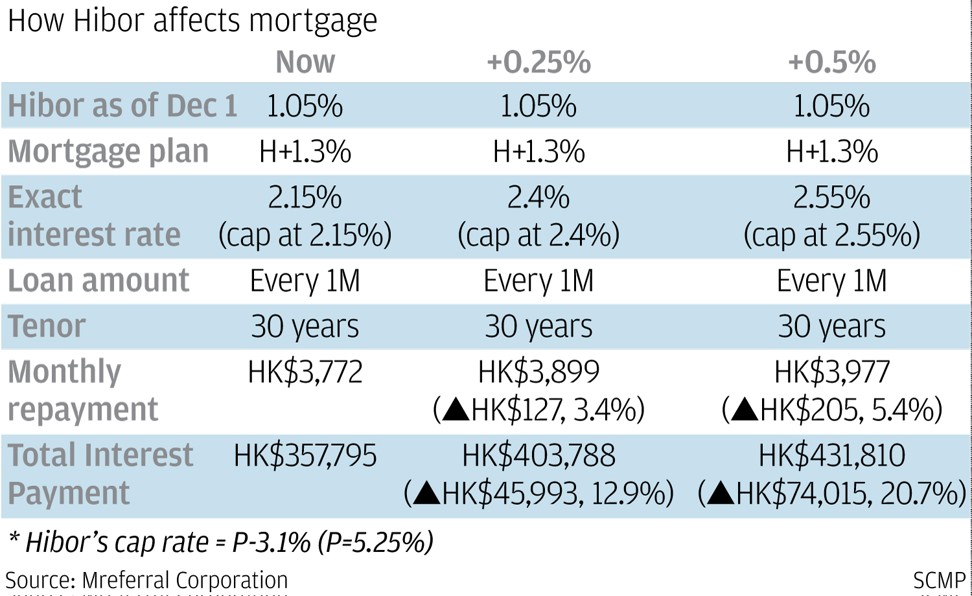

An increase in Hibor will also lead to a rise in the cost of borrowing for individuals and companies. Interest rates on non-fixed mortgages are either set a certain percentage above Hibor, 1.4 per cent for Hong Kong’s largest banks, or a percentage below the prime rate, normally 2.7 per cent.

Commercial banks’ prime rates are currently set at 5 per cent (for example, HSBC, Bank of China Hong Kong and Hang Seng Bank), or 5.25 per cent (for example, Standard Chartered and Bank of East Asia). The two rates are connected.

“The main consideration for a commercial bank such as HSBC, when setting the prime rate, is the level of Hibor as that sets the cost of funding,” said George Leung, an adviser at HSBC Asia-Pacific. “Of course, banks get money from other sources, such as savings. But if Hibor rises then the banks that get money from the market will have pressure to raise rates.”

“I expect banks to raise their prime rate towards the end of the first quarter next year,” said Helen Chan, the head of treasury, OCBC Wing Hang.

With both rates rising, the cost of mortgage repayments will too – something officials have been warning about.

“I completely understand that, for many Hongkongers, buying a house is the most important lifetime investment decision,” Paul Chan Mo-po, the Financial Secretary, wrote in a blog in March. “But the basic market conditions have fundamentally changed, and homebuyers should pay extra attention to all kinds of risks before any decision is made.”

HSBC’s Leung, however, said an uptick in interest rates would not have a significant effect on borrowers’ ability to repay. “Banks carry out substantial risk assessments on their borrowers, so a rise of one or two percentage points shouldn’t make a big difference,” he said.

OCBC’s Chan said there were two factors influencing the banks’ decision to raise their prime rate, the level of Hibor and the banks’ loan-to-deposit ratios.

Both have been rising in the second half of this year.

If banks have much more cash in deposits (on which they pay very low interest rates) than they can lend in loans, then they can lend cheaply. According to HKMA data, the banks’ Hong Kong dollar loan-to-deposit ratio in September was 78.8 per cent, up from 75.7 per cent in February.

“The main reasons for the recent rise in Hibor were actions taken by the HKMA, which removed HK$80 billion in liquidity from the market between July and October, and tighter liquidity on the mainland, which also affects Hong Kong,” said Irene Chow, senior China and Hong Kong equity analyst at Julius Baer. “The HKMA seems to have been concerned about the gap between the US dollar Libor and Hibor, and so took action. If this gap remains, I imagine that it will take further action.”

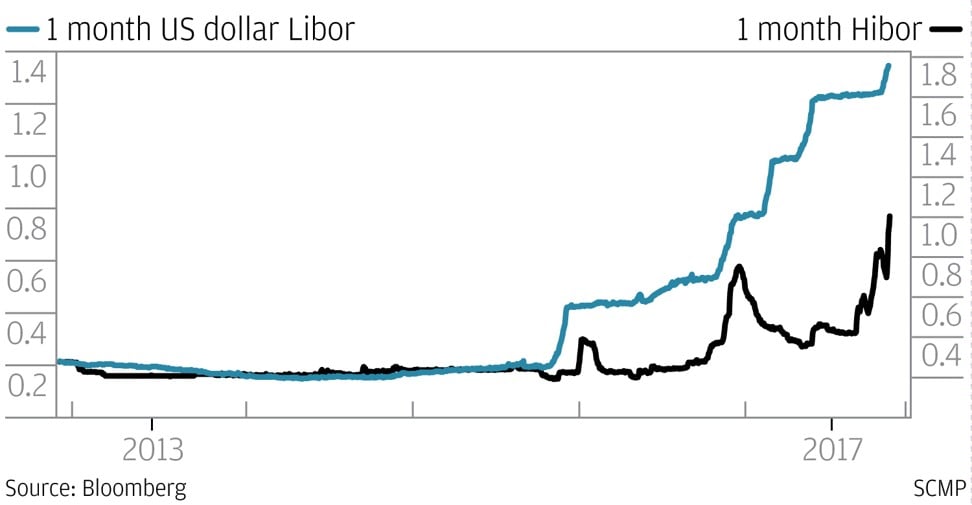

Libor, or the London interbank offered rate, is a benchmark for the US dollar, and has risen in stages as the Federal Reserve has raised rates.

Hibor, however, has lagged behind and only started to tick up in the autumn. “Hibor barely moved until October. But the 3-month Hibor, despite being at a multiyear high, is still lower than the 3-month Libor, so I believe there’s still room for the Hibor to move higher,” said Ben Luk, a global macro strategist at State Street Global Markets.

Analysts expect that banks will wait until early next year to raise rates, rather than doing so after the expected increase by the Federal Reserve – and hence, the HKMA – this month.

“There are two factors that will impact [the Hong Kong] banks’ decision – the spread between Hibor and Libor as well as the aggregate balance that the HKMA controls when it comes to liquidity,” said State Street’s Luk.

The aggregate balance is the amount of money banks have in clearing accounts with the HKMA.

“This is now half of the liquidity compared to the peak, but at HK$184 billion it is still quite hefty,” said Luk. “There’s growing concern that banks will raise prime lending rates in the short term, but there’s really no rush for them to raise rates and follow the Fed’s normalisation path given the still ample liquidity in the banking system.”

OCBC’s Chan said that other reasons for the spike in Hibor were the recent large IPOs in Hong Kong, which had driven demand for Hong Kong dollars, and usual tightening at the end of the year. “I would expect liquidity will ease slightly in the new year, with fewer IPOs planned, and so banks will raise their prime rates towards the end of the first quarter rather than early in the year,” she said.

Anil Agarwal, the head of banks research at Morgan Stanley, agreed, but for slightly different reasons.

“We think it will probably be difficult for banks to raise prime rates without increasing savings deposit rates, as it is unlikely this would be well received by the general public and retail depositors,” he wrote in a note to clients.

“Based on this, we think it is unlikely that Hong Kong banks will increase prime rates after the December FOMC meeting – unless banks become concerned about losing savings deposits. We assume that the first prime rate hike is likely to be after the first Fed hike in 2018.”

The first rate increase by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), the body in the US that sets the base rate, is expected in the first quarter.

HSBC’s Leung said it might take even longer. “It is possible, but I do not think banks will raise their prime rates as early as the first quarter next year,” he said.

“In the last interest rate rising cycle, before the global financial crisis, banks tried to keep a spread between Hibor and the prime rate of 200 to 300 basis points. This time, it is harder to say what the level will be, as banks’ costs are higher than in the past, but competition will add pressure to keep rates down, so it might be similar. If so, we still have further to go as the gap between prime rates and Hibor is around 400 basis points.”

Nonetheless, in a sign that access to funding may be becoming a bit tighter, banks are now starting to raise interest rates on savings. Last week, BEA increased its highest fixed interest rate for Hong Kong dollar savings accounts by 20 basis points to 1.27 per cent.

“[BEA] takes into account a number of factors, including the movement of Hibor, competitors’ rate and bank strategy, in determining our fixed deposit rates. Due to the said factors, we have slightly increased Hong Kong dollar fixed deposit rates recently,” said a spokeswoman for the bank.