The View | Jury’s out on central banks’ resolve to face down markets

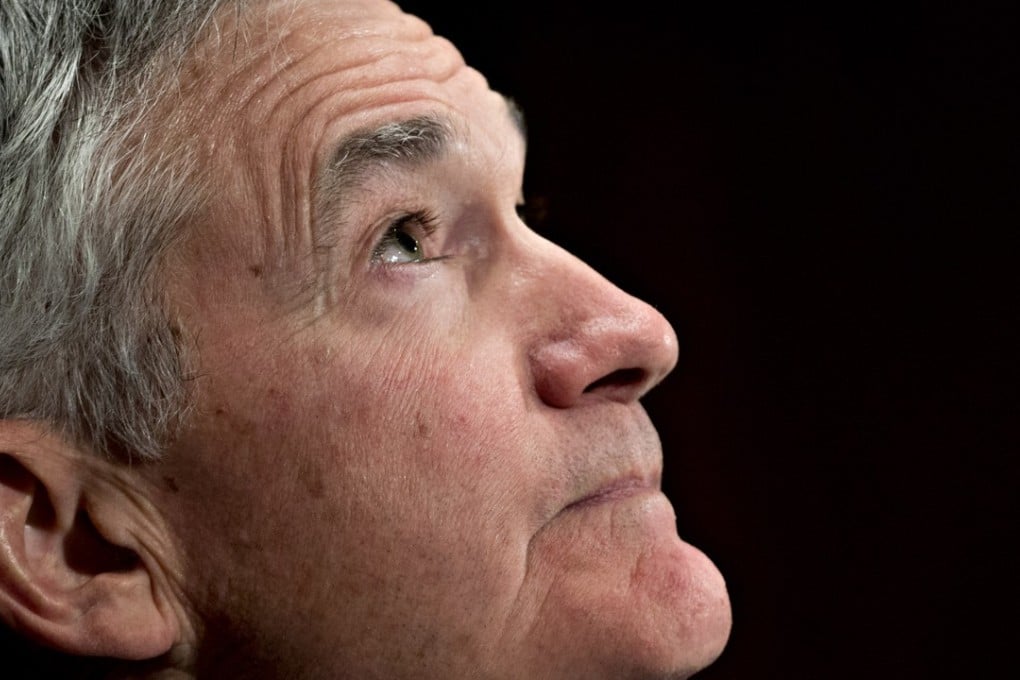

Is the new US Federal Reserve chairman Powell the bold policymaker long sought by the Bank for International Settlements?

For the last several years, the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), the so-called central bankers’ bank, has repeatedly warned the world’s main central banks of the dangers of delaying their exit from years of ultra-loose monetary policy.

As far back as June 2014, the BIS said central banks were being too “hesitant” to remove stimulus “out of concerns about disrupting [financial] markets” and that “the risk of normalising [policy] too late and too gradually should not be underestimated.”

The ‘Powell effect’ is already palpable in the Fed Funds futures market, contracts that reflect market views of where US rates will be at the time the contracts expire

Last week, Jerome Powell – the bold new chairman of the US Federal Reserve – who unlike the last three chairs is not an academic economist and has extensive experience working in the private sector, gave the strongest hint yet by a leading central banker that rising volatility in markets is not a sufficient reason to refrain from withdrawing stimulus.

Indeed not only did the new Fed chair strike a distinctly hawkish tone in his testimony to Congress last Tuesday, he signalled that stronger data on growth and inflation strengthen the case for a faster pace of interest rate rises than markets are currently pricing in.

The “Powell effect” is already palpable in the Fed Funds futures market, contracts that reflect market views of where US rates will be at the time the contracts expire.

The odds of four or more rate rises this year – one more than the Fed currently anticipates – has shot up to 35 per cent, its highest level on record.