Coronavirus has sparked an ‘infodemic,’ with stock markets battered by news spreading panic via smartphones and tablets, say analysts

- People are hard-wired to be cautious and watch the herd. But by the time they react, markets usually have already fallen, says behavioural economist

- China plays a bigger role in the global economy now – meaning what happens in China is magnified around the world

Feeling spooked yet?

If so, you belong to a rapidly growing crowd around the world reacting strongly to the coronavirus outbreak. The respiratory illness that began in mainland China has upended global stock markets, supply chains, company earnings and investors’ portfolios.

China’s bigger role in the global economy – it accounted for 4.3 per cent of the world’s GDP in 2003 during the Sars outbreak versus 16.5 per cent now – is part of the reason the coronavirus is causing so much turmoil. Global heavy hitters from Apple to Starbucks have raised alarms about the virus’ impact on revenue tied to China.

Meanwhile, global stocks were on track for their worst week since the financial crisis in 2008. Hong Kong stocks – as well as those on the mainland – fell hard on Friday.

That all means that what happens in China doesn’t stay in China any more.

But the huge amount of time we all spend on smartphones, tablets and desktops gathering the latest scary headlines is also a factor in what happens to stock prices, according to markets data provider Refinitiv, which this week put out a report on fear cycles over time.

It found spikes in words like “infectious disease” and specific countries on internet websites and on social media were followed later by drops in stock prices.

Worse than financial crisis, deadlier than Sars: coronavirus to push Hong Kong bankruptcies to decade high

The coronavirus outbreak is the first “infodemic,” its analysts say, because of how much more we are all glued to online news.

Reacting strongly to fear signals is hard-wired into humans. Our adrenaline surges. Our heart rates shoot up. Our vision becomes focused.

“It’s irrational and it’s fear, but it’s important in financial markets because it changes economic behaviour,” said behavioural economist Richard Peterson, the CEO of MarketPsych and author of Inside the Investor’s Brain: The Power of Mind over Money.

“[Markets] … are driven by information flow and opinion and speculation. That is what we are getting with the virus. The virus is still spreading, so we are not at the bottom yet, necessarily. Once it stabilises a bit, you will see the bottom process.”

It usually takes about a week for markets to react to news, Peterson told the South China Morning Post. Diseases differ from other market-moving events in that they are entirely based on fear of the damage they cause to such things as travel, workplaces and supply chains, he said.

Coronavirus puts global economy at risk of worst year since 2009 crisis as hopes fade, stocks plunge

“There is a psychological impact from the uncertainty and future forecasting that is greater versus a tangible news release like a Chinese economic slowdown or bad winter in the US that is quickly stale news. Diseases are prolonged and very speculative,” he explained.

So can mom and pop investors take advantage of these fear cycles? That’s not the best idea, says Peterson, who stresses he is not a stock adviser. Charting moves based on technical analysis is best left to the professionals, he said. Such trading has been likened to trying to catch a falling knife.

Some of the information swirling around on the internet isn’t even accurate – or is intentionally fabricated. The World Health Organisation’s director general, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, has called on countries to push back against the “infodemic” of such fake news, which he said was equally dangerous.

WHO has been working with Google “to make sure people searching for information about the new coronavirus see WHO information at the top of their search results,” he said.

Another reason the coronavirus will play out differently than Sars is because markets in 2002-2003 were at a low, unlike recently, notes Stephen Innes, Asia-Pacific market strategist at AxiTrader, an online foreign exchange trading platform.

Coronavirus: how the WHO is leading the social media fight against misinformation

“Will things come back? Yes, for sure. But the fire sale on the equity market is not nearly cheap enough for my tastes. I think once we see a concerted G20 fiscal pump, the first thing to jump into will be growth and tech stocks and then timing the travel ban reversal will be a considerable boon for tourism and luxury. But when that happens is anyone guesses,” Innes said.

China is not pumping in adequate stimulus, Innes warns.

“The biggest threat to the global economy is not just because the disease spreads quickly across countries through networks related to global travel,” he added.

“But also because any economic shock to China’s colossal industrial and consumption engines will spread rapidly to other countries through the increased trade and financial linkages associated with globalisation.”

“Mainland regulators will not let this virus snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, so I expect them to use everything in their tool kit, including the kitchen sink, to right the economic ship. Hopefully, they don’t wait too long as they can’t possibly take the chance for this thing to get worse,” Innes added.

Since Sars, China has transformed into a global powerhouse and become deeply embedded in the world’s supply chains. Worldwide economies emerged relatively unscathed from the last epidemic.

With China’s slice of the world GDP about four times what it was in 2003, the coronavirus poses a huge risk to already slowing global trade as manufacturers from Europe to America depend on Chinese factories that have not yet fully returned to production during the virus.

Disruptions have been felt as far away as France, with finance minister Bruno Le Maire saying the epidemic would knock 0.1 points off growth, highlighting the European country’s reliance on China.

And the country’s increased integration with South Korea and Japan – themselves reporting growing numbers of Covid-19 cases – only worsens shock waves being felt worldwide.

The three Asian countries contribute about 24 per cent of the world’s economy, with a combined yearly trading volume of over US$720 billion, making up one of the most integrated international economic blocs in the world.

“If the epidemic spreads in Japan and South Korea, it will bring a second blow to the global industrial chain and impact downstream companies in China,” said Song Xuetao, an economist at Tianfeng Securities.

Factory shutdowns in China and South Korea have caused a significant decline in shipping, with 46 per cent of scheduled shipments between Asia and northern Europe cancelled, according to ocean freight data firm Alphaliner.

Many Chinese manufacturers cannot run at full capacity, with shortages of supplies like masks, and staff unable to return to work. IHS says the lifting of all travel restrictions and full resumption of operations are unlikely unless there are no new cases nationwide for at least two weeks.

Meanwhile shipments have stopped coming to China, home to seven of the world’s 10 largest container ports including Hong Kong, for fear of contagion. Container throughput in China is estimated to drop by 20 per cent to 30 per cent in February, according to shipping research company Clarksons.

Chinese President Xi Jinping said, “priority should be given to ensure leading companies that are important in the global supply chain restore production and supply, maintaining the stability of the supply chain.”

To be sure, earlier diseases saw drops in stock prices, as well, on fear.

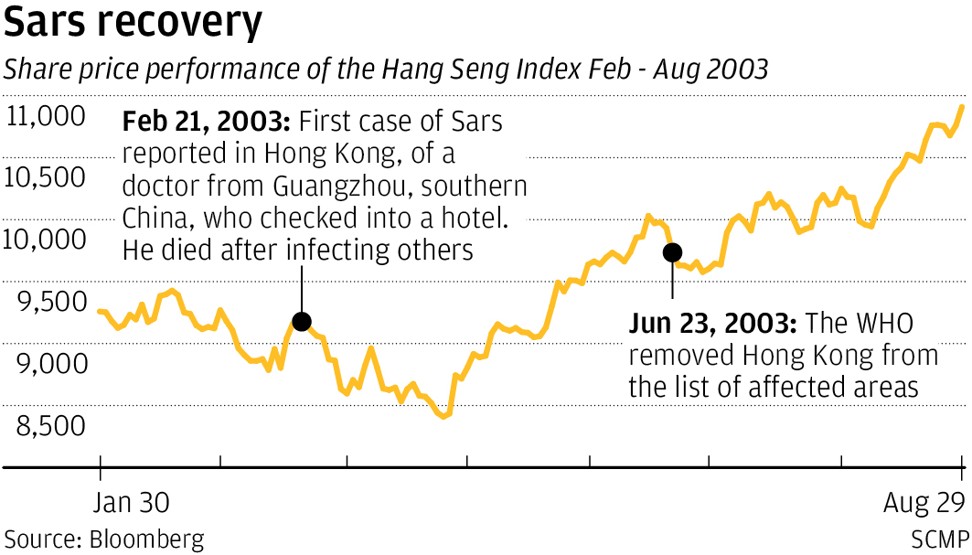

Stocks fell during Sars in 2002-2003. The Hang Seng Index, for instance, lost 14.8 per cent to its lowest point on April 25 from its high on January 15 that year.

This week, the Hang Seng fell 4.3 per cent. It has fallen 6.5 per cent since January 24, as the coronavirus epidemic escalated over the Lunar New Year holiday.

Airlines, property firms, retailers, restaurants, cars, beers and other consumer product stocks have been hit over the past two days in Hong Kong.

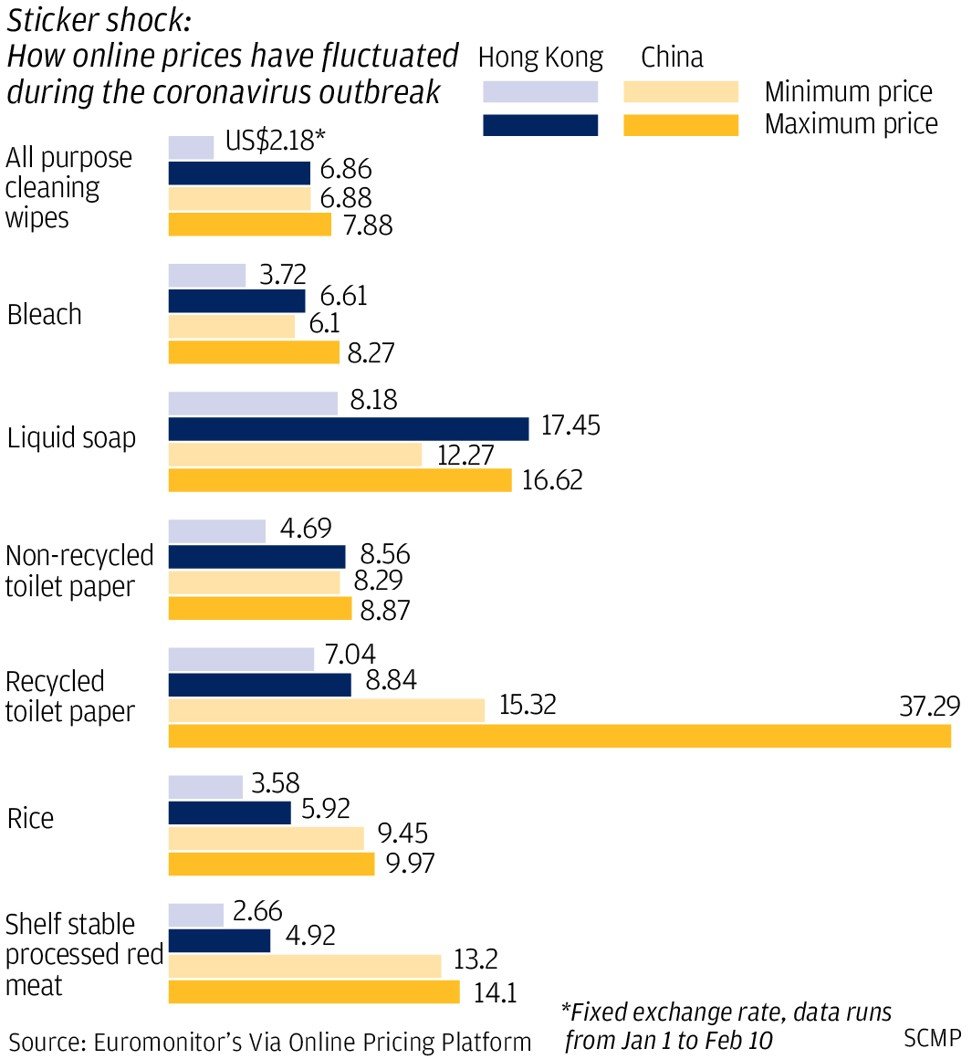

But since January 24, online health care stocks have advanced, as cities in lockdown relied on their services for supplies.

PingAn Good Doctor, China’s largest online health care platform, jumped 9 per cent over the period. AliHealth, an online pharmacy backed by Alibaba, the owner of the South China Morning Post, surged 38.8 per cent.

The Shanghai Composite Index has declined 3.2 per cent since January 23, the last day of trading before the Lunar New Year holiday. But this week, it fell 5.2 per cent, as fears mount that the virus could turn into a pandemic as cases rise beyond mainland China.

A-shares of airline stocks have tumbled since China imposed city lockdowns, while foreign countries also imposed travel and visa restrictions to and from China.

Between January 23 and Friday, Air China tumbled 9.6 per cent, China Southern Airlines dropped 10.4 per cent and China Eastern Airlines plunged nearly 11 per cent.

Over the same period, medical-related stocks bucked the trend. Shenzhen Mindray Bio-Medical Electronics, China’s largest hospital devices maker, surged nearly 27 per cent. Shanghai-listed Zhende Medical, jumped 37.1 per cent.

While stocks have fallen in previous disease outbreaks, coronavirus may end up being more pronounced, said behavioural economist Peterson.

“The fear and monitoring of the virus is so much more acute than it was in the past, that much more detailed,” he said.