Here’s how a global asset shopper gets under the radar by hewing close to China’s state policy

A Chinese energy company founded 15 years ago by an entrepreneur in his mid twenties had been quietly gobbling up energy assets across central Asia and eastern Europe for the past two years.

Unlike Anbang Group, Dalian Wanda Group, Fosun Group and the HNA Group, which have come under close regulatory scrutiny since April for their global acquisitions, CEFC China Energy has largely stayed out of the spotlight.

The Shanghai company spent at least US$1.7 billion since 2015 buying energy-related businesses in Romania, the United Arab Emirates, Russia, and even Chad, and another US$1.2 billion buying financial services in the Czech Republic and the United States.

What differs between CEFC and its better known -- and larger -- peers is that its acquisitions have hewed close to state policies, in particular Chinese President Xi Jinping’s Belt & Road Initiative, which connects China’s market and products all the way to Europe and Africa along a modern iteration of the Silk Road.

In so doing, CEFC not only escaped the wrath of state regulators wary of wayward asset buyers, it’s also manage to secure government funding for the lion’s share of its purchases.

“Beijing’s main concern with so-called irrational overseas acquisition is that they may be dressed up as deals in line with the state’s policy to encourage corporations to expand abroad, but are in reality transactions to facilitate capital outflow,” said Junyang Securities chief executive Kenny Tang Sing-hing.

After working briefly as an enforcement officer with the forestry department, he earned his first pot of gold helping to extricate a Hong Kong businessman from financial strife and complete a real estate transaction, according to Depth-paper, a Chinese news portal.

From there, he bought at auction the oil businesses that the government had confiscated from Xiamen’s smuggling kingpin Lai Changxing, using loans from state banks, as well as investors in Hong Kong and Fujian to finance his purchase, he told Fortune in an interview.

By 2015, Ye had built up a business empire with 263 billion yuan (US$39 billion) in revenue, 60 per cent of which was from the trading of oil and gas. CEFC then embarked on an overseas shopping spree, starting with a US$680 million purchase of a majority in the overseas unit of Kazakhstan’s state oil company. Subsequent acquisitions extended across eastern Europe, the Middle East and Africa, mostly in oil and gas.

“We can also use it as a springboard to develop business relations with Western Europe.”

After Xi Jinping, a self-professed football fan, ascended to China’s presidency in 2012, scores of Chinese companies rushed to buy European football teams, star players and coaches, seeking to import foreign talent to improve the moribund Chinese national team.

CEFC wasn’t spared from the faze, buying the Czech football club Slavia Praha. Along the way, it bought the five-star Mandarin Oriental hotel in Prague, a 50 per cent stake in the Czech-Slovak financial firm J&T Finance for US$1.1 billion, as well as stakes in the largest Czech airline and the country’s largest online travel agency.

By last year, Ye was no longer completely under the radar. He was second place on Fortune magazine’s “40 Under 40” list of the world’s most influential young people, two spots ahead of French president Emmanuel Macron. A 2016 Fortune interview described him as a “mysterious tycoon” and “a rare powerful private player aligned with the Chinese government”.

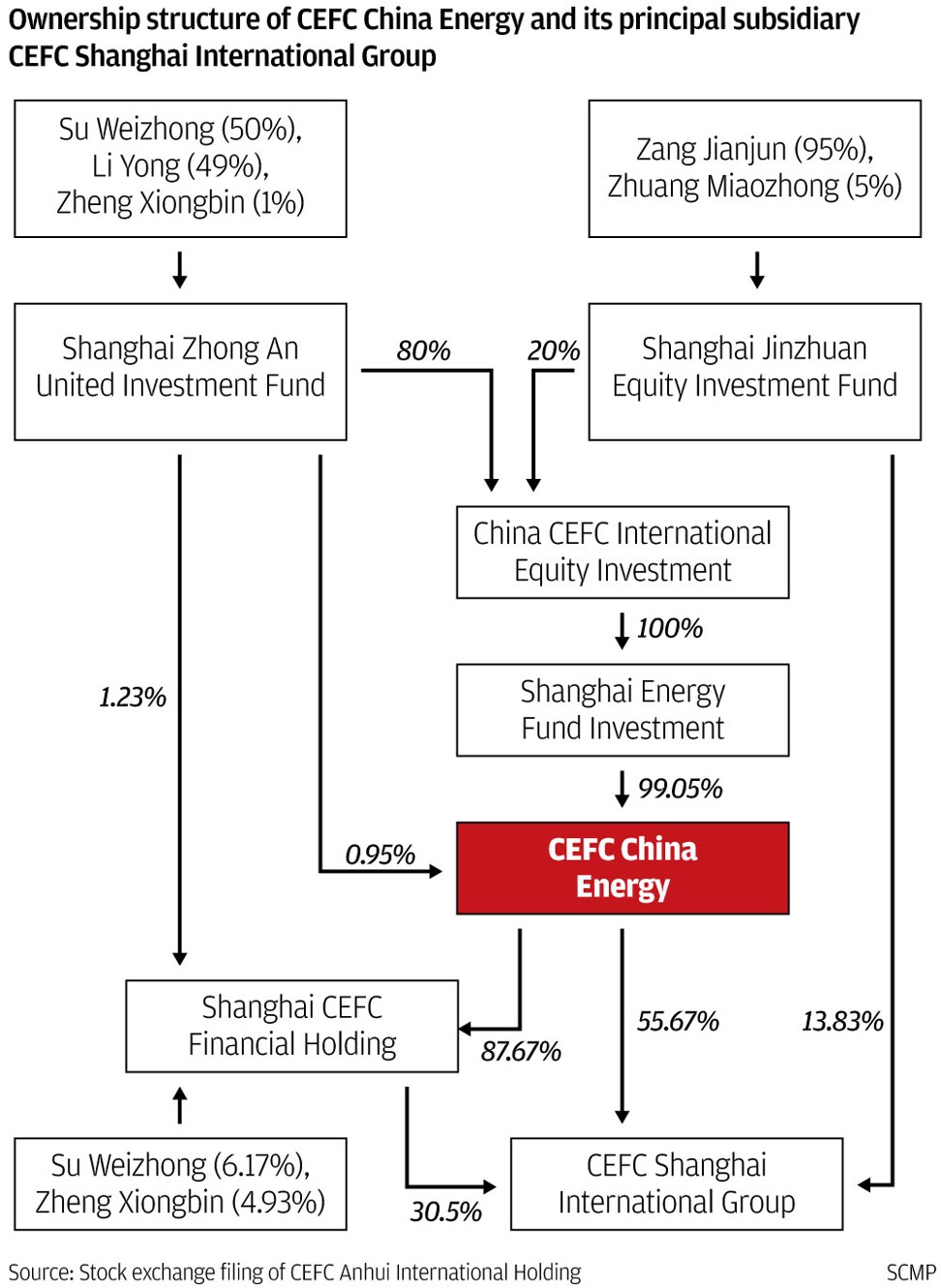

Ye is listed as CEFC’s founder and chairman, but doesn’t appear anywhere on the shareholders list. Instead, the company is split between five shareholders who are all senior executives within the company’s corporate structure.

CEFC’s Shanghai spokesman declined to say why Ye is not listed as a shareholder.

Still, its shareholding structure didn’t hinder CEFC’s financing, as the company boasts of what it calls a “full suite” of operating licenses in the financial industry, including securities dealing, trust, futures, banking, insurance, leasing and asset management. It also set up global buyout funds with domestic and major overseas financial institution partners, CEFC said.

CEFC had 44.4 billion yuan of credit line as of March 2016, drawing down 83 per cent of that available financing.

China Development Bank, the country’s main policy lender, was CEFC’s biggest creditor, extending 32.3 billion yuan of loans, or 87.5 per cent of total bank borrowings, according to the September 2016 bond prospectus of its principal subsidiary CEFC Shanghai International Group.

CEFC Shanghai recorded 3.1 billion yuan of net profit on 206.6 billion yuan of revenue in 2015, contributing the lion’s share of the company’s total earnings.

With debt at 70 per cent of assets at the end of 2015, CEFC expanded its financing channels including some in Hong Kong to help finance its investment spree.

Besides pursuing Hong Kong-listed Runway Global as a fund-raising platform, CEFC’s main unit obtained a HK$600 million loan facility from Huarong Internatioal Financial in February to fund a US$175 million oil and gas acquisition in Abu Dhabi.

The subsidiary also raised HK$900 million last month by issuing preference shares to Huarong International, convertible into common shares if its Hong Kong unit is listed on the city’s bourse.

Citic CLSA late last year also helped the principal subsidiary raise US$250 million via a bond issuance in Hong Kong.

“Some mainland enterprises are privately-owned on the surface but are actually agents for the government and state agencies,” said Tang. “They are packaged as private firms for making overseas acquisitions that would otherwise be politically more sensitive if conducted by state enterprises.”

CEFC’s spokesman rejected any suggestion that the company’s founder gets any preferential treatment from the Chinese government.

“I can responsibly tell you that he has no special background,” he said.