September could be an important inflection point for global markets

Central bankers face difficult policy choices amid growing inflation risks

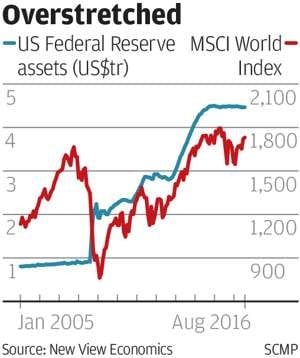

There is an ominous sense of déjà vu about the state of the world economy right now. Global growth looking very tired, buoyant stock markets increasingly divorced from underlying fundamentals and global policymakers struggling to contain burgeoning financial risks. We have seen it all before and it would be a disaster to see the return of a new storm.

We saw a similar build-up in the run-up to the 2008 global financial crash and we are seeing parallel trends once again. In the years leading up to the crash, an explosion of global credit, untamed financial engineering, the proliferation of exotic investment products and excessive exuberance by investors, ended up in a disaster of epic proportions.

Should they start to put the brake on super-stimulus long before inflation risks begin to break higher and stock market sentiment starts to fold?

The collapse of the subprime mortgage market in 2008, catapulted the global economy into recession, deflation, doom and gloom from which the world is still trying to recover. The consequences are still being felt in the shape of the brave new world of monetary invention the central banks have created with quantitative easing programmes and zero interest rates intended to put the world economy back on the road to recovery.

However, it is becoming increasingly clear these tools for recovery are not without their risks. Global financial markets are becoming far too pumped up by the central banks’ derivative money glut. The subsequent return of excessive speculation, leverage and risk are leaving investors and the global economy seriously exposed to the chances of a new crash. Next time round there may be no more effective policy tools left to deal with any new disorder.

The worry for policymakers is this vast pool of engineered central bank money is becoming less effective on helping the real economy – what economists call diminishing marginal returns. If QE and zero interest rates are doing nothing more than pumping up irrational exuberance and excessive speculation in financial markets, it poses a big dilemma for policymakers. Should they start to put the brake on super-stimulus long before inflation risks begin to break higher and stock market sentiment starts to fold?

Global central banks are trapped between a rock and a hard place. Once they begin the process of withdrawal it will be like waving a red flag at a bull. Stock market zeal could go into very sharp retreat. It is the reason why the US Federal Reserve has been so reluctant to tighten interest rates too dramatically and strenuously avoided downsizing its US$4.7 trillion pile of QE assets.

For the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan, there is no easy way back either. Europe and Japan are hooked on this massive credit creation, knowing any hint of hesitation could put markets into a dramatic tail-spin. For the time being, it is a question of grin and bear it and hope for an easy way out at some stage. Central banks are trapped in a vortex of their own making.

The potential risks to global financial stability are not going unnoticed. Market surveys show that mainstream investment funds are starting to get much more circumspect about the deteriorating investment climate. So far in 2016, they have cut their equity market exposure to multi-year lows and built up greater protection in safe haven government bonds like German bunds and US Treasuries.

If mainstream investment funds are becoming more risk averse, it means leveraged, speculative and proprietary money is doing most of the ramping up in equity markets. This leaves risk sentiment dangerously exposed in the event of a downturn in confidence. If the going gets tough, this fast money is guaranteed to hit the exits very hard, risking a market panic in the process.

The cardinal error is that the central banks rushed headlong into a policy labyrinth from which there is no easy way out. If they rock the boat now they risk upsetting global financial markets with consequences which could be even more dire than the 2008 crash.

They have two alternatives. The easy option is the central banks stick with the white knuckle ride and hope it has a happy ending. This is not a likely outcome considering the dangerous build up of global credit and debt in recent years. Inaction is more likely to end in tears.

The tougher option is that the central banks call it a day and gradually begin to rein in the excessive monetary stimulus. Later this month, the Fed can take the next step towards policy normalisation with its next rate rise. It is time to put its money where its mouth is.

David Brown is chief executive of New View Economics