Why China is right to try to end its bubble addiction

Andy Xie says China has recognised that tightening the money supply is the way to rein in the excesses of the past, and, along with curbing corruption, is good for long-term economic health

China's economy is slowing. It is good news. It reflects that China's economy is finally ending its bubble addiction. Even better, the central government remains calm over the slowing news. All signs point to China's new leadership taking the plunge to digest the excesses from sometimes crazy stimulus policy under the previous government.

From 2004, China pursued a bubbly path by refusing to rein in monetary growth despite inflationary pressure and an emerging labour shortage. The bubbly path was amplified by a slow but steady appreciation of the renminbi against the dollar.

The perception of a sure winner enticed a huge amount of hot money to flood into China. The resulting liquidity orgy caused one asset bubble after another.

After China joined the World Trade Organisation, it became the factory for the world. The success is due to the competitiveness of Chinese workers. China's wealth is created at factories and construction sites by workers who are as productive as their counterparts in the West but paid one-eighth to one-tenth as much.

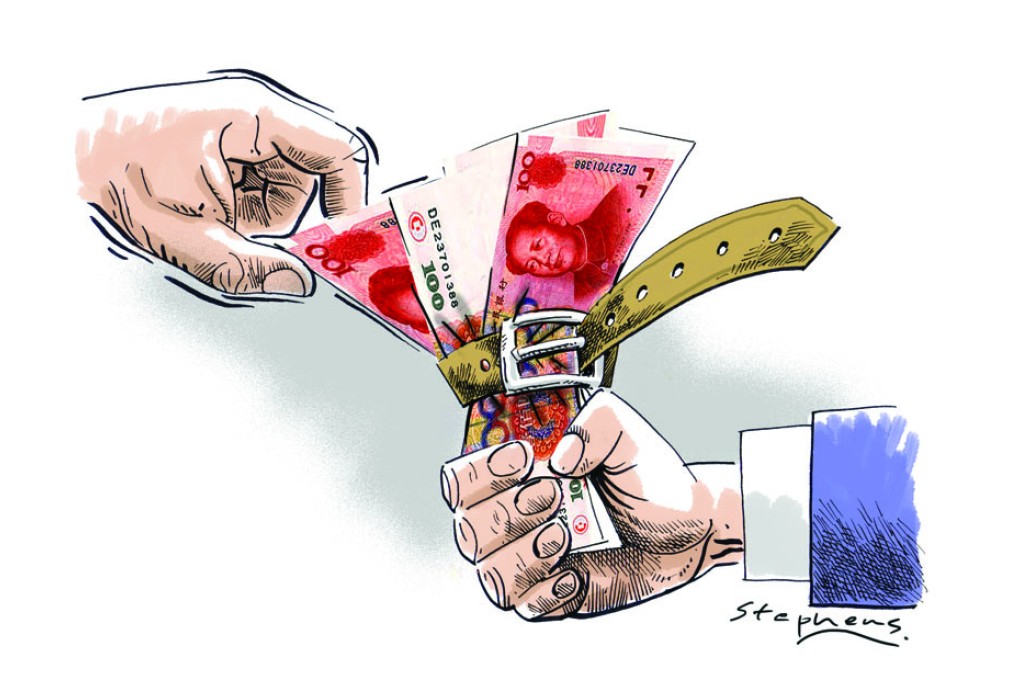

A consequence of China's bubbly path is wealth redistribution to the vested interests, who can line their pockets from negative real interest rates. As the credit bubble lasts, the credit-to-GDP ratio has surged. China's credit is twice its gross domestic product.

The real interest rate should be equal to total factor productivity. In China's case, it should be 4-5 per cent. Instead, if one uses a GDP deflator as the real gauge for inflation, China's real interest rate is about minus 5 per cent. The macro policy redistributes a percentage of GDP from the people to vested interests. This is the biggest reason that China's household consumption is one-third of GDP instead of a normal 50 per cent for such an emerging economy.