Macroscope | Great Game between China and US alive and well

This week three “great powers” have big stories at home – and almost no one in the rest of the world is taking any notice.

In the UK today (okay, arguably no longer a great power) a historic, perhaps game-changing election is riveting the nation – alongside the birth of Princess Charlotte.

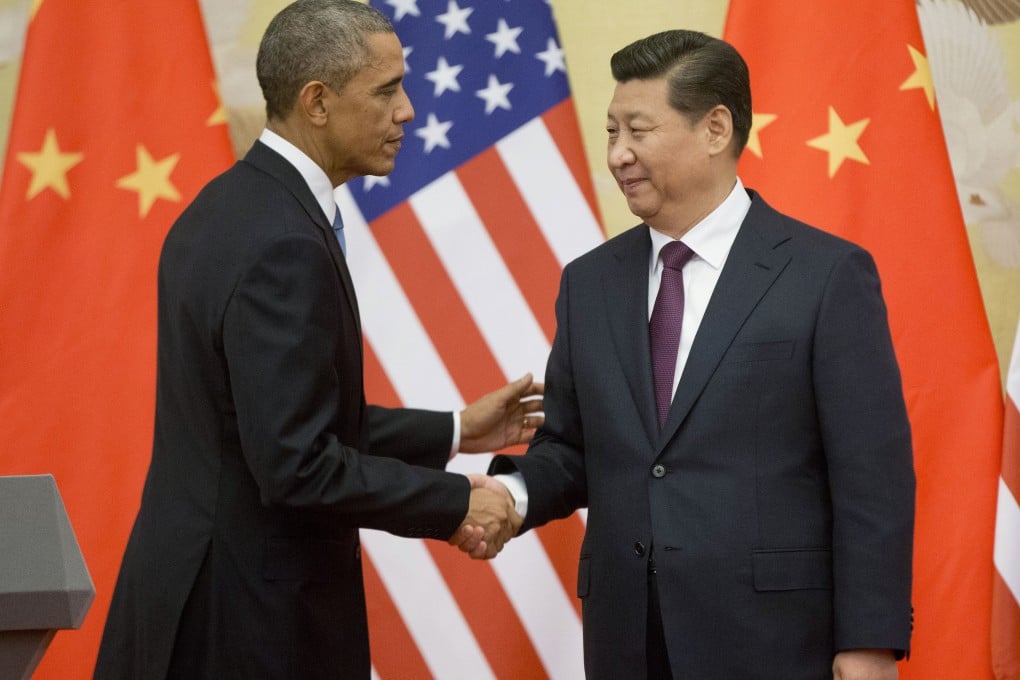

In the US, President Barack Obama is at last girding his loins to fight for the “fast track” negotiating authority that will enable him to get the world’s biggest free trade agreement – the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – past the finishing line.

And in China, Xi Jinping prepares to visit Russia and two of its satellites.

In diplomatic terms, the “great game” continues to be played as it was 100 years ago – and the same old proverb applies - the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

I sense a great indifference in Hong Kong to Britain’s Lilliputian election – though it provides a marvelous example of how even the most time-honoured democracies find themselves sullied by tawdry, unprincipled compromises with political enemies in the cynical quest for power.