Advertisement

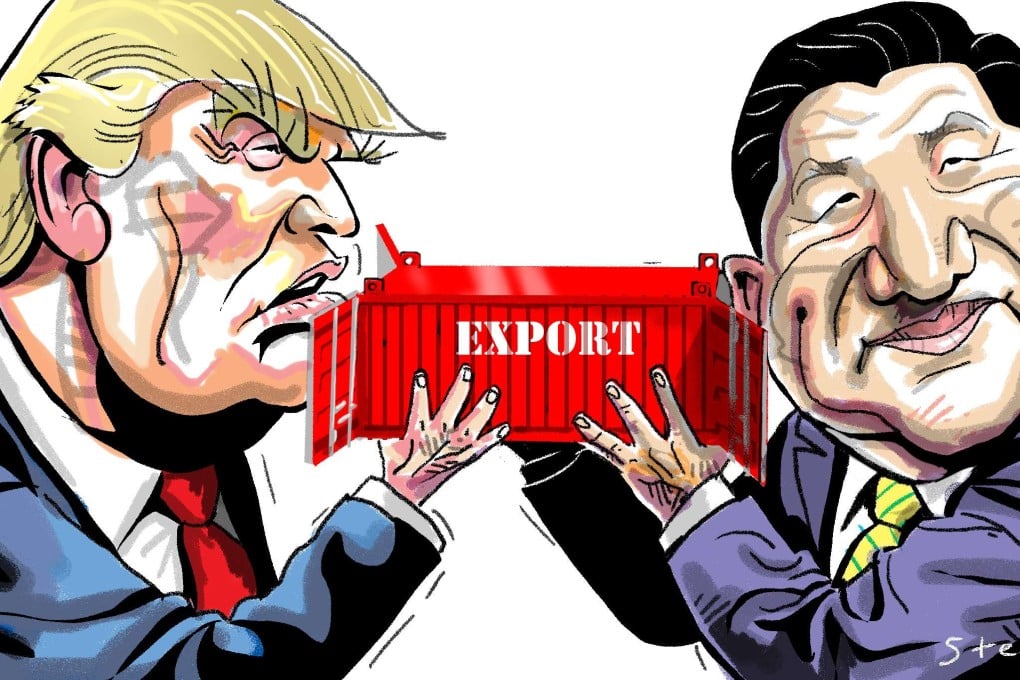

China and the US must narrow the trade gap by boosting trade, rather than curbing it

John Gong and Yabin Wu say the 100-day negotiation aimed at reducing the US trade deficit must work on increasing American exports to China, instead of reducing Chinese imports to America

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

This time round, at the meeting in Florida, although US President Donald Trump does not have a figure as slim as Obama’s, the fundamental basis of the Sino-US relationship remains solid. US policy towards China, and for that matter China’s towards the US, is unlikely to change much from the days of the Obama administration, no matter how much rhetorical bluff Trump had tweeted before (and after) the election. Both countries, after all, share many common interests in tackling global issues like North Korea, nuclear non-proliferation and climate change.

The timing of Xi’s visit could not have been better.

Advertisement

On the day Trump welcomed him at the Mar-a-Lago estate, tomahawk missiles were hitting targets in Syria, in response to the Syrian government’s alleged use of chemical weapons in the country’s civil war. All of a sudden, speculation about the Trump campaign’s connections to Russia subsided in Washington. And, all of a sudden, Trump was boasting about his rapport with Xi on TV.

Indeed, reports of the Xi-Trump summit suggest rosy days ahead between the two countries.

Advertisement

It appears that some kind of agreement has been reached on a range of issues. Most important to the US is China’s commitment to cooperate on the North Korea nuclear issue. Hence, Beijing’s orders to turn back North Korean ships loaded with coal. In turn, the Trump team appears to have calmed down over its two major complaints against China during Trump’s presidential campaign: the White House now says it will not label China a currency manipulator, and there has been no more mention of punitive tariffs on Chinese exports to the US.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x