Why the US is not slipping into a recession, despite the inverted Treasury yield curve

- While an inverted yield curve could be taken as a sign that a recession is in the offing, US manufacturing activity and consumer sentiment remain robust. The inversion in US yields is more a by-product of excessively low yields in Europe and Japan

James Carville, a prominent American political consultant who played a key role in the successful presidential campaign of Bill Clinton in 1992, famously said: “I used to think that if there was reincarnation, I wanted to come back as the president or the pope or a .400 baseball hitter. But now I want to come back as the bond market. You can intimidate everybody.”

The pessimism has been most evident in the US Treasury yield curve.

The gloom in bond markets has put other asset classes under strain, particularly equities and emerging markets which have benefited significantly from this year’s dovish U-turn in US monetary policy. The benchmark S&P 500 index is down nearly 2 per cent since last Thursday while the MSCI Emerging Markets Index, the main gauge of stocks in developing economies, has lost just over 2 per cent.

A global growth scare – which contributed to the fierce sell-off in the final quarter of last year but receded in the last few months – threatens to put an end to this year’s blistering rally which, according to a report published by JPMorgan last Friday, has resulted in the best quarter for US stocks in a decade.

The question, however, is whether the worrying signals that bond markets are sending are an accurate barometer of economic sentiment, particularly in the US, given the inversion of a portion of the country’s yield curve.

There are strong grounds to believe they are not.

For starters, the inversion last Friday had little to do with the US economy and was mainly attributable to the publication of survey data showing that Germany’s manufacturing sector slid deeper into contraction territory this month, fuelling concerns about the euro zone’s largest economy and the broader slowdown across the bloc.

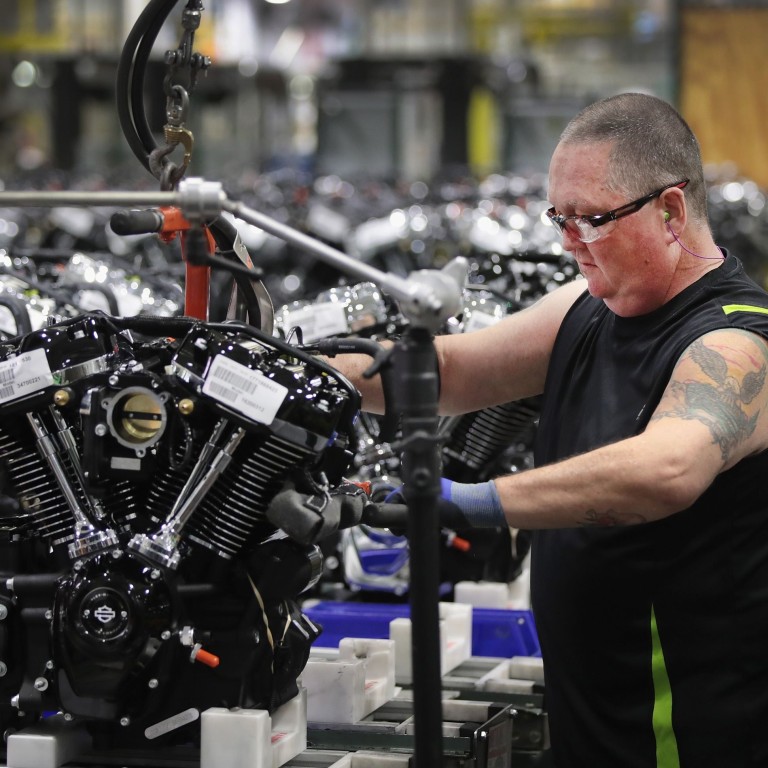

US manufacturing activity, by contrast, although slowing, is still firmly in expansion territory. What is more, consumer sentiment – a more important gauge given that household consumption accounts for 70 per cent of US economic activity – remains elevated, buoyed by the fastest growth in wages last month since 2009.

Make no mistake, America is not about to fall into recession.

Indeed, the scale and persistence of price distortions in global debt markets stemming from years of ultra-accommodative policy call into question the reliability of any signal from bond markets. In a sign of the extent of these distortions, the global stock of government and corporate bonds trading with a yield below zero surpassed the US$10 trillion level last week for the first time since September 2017 and now accounts for nearly a fifth of the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate Bond Index, a benchmark index.

Ultra-low bond yields in Japan and the euro zone are acting as an anchor, pulling Treasury yields down

That is not to say that the gloom in debt markets is entirely misplaced. A gauge of global manufacturing activity last month compiled by IHS Markit, a data provider, dropped to its lowest level since June 2016, with growth slowing in the US and contractions in the euro zone and Japan.

Yet as JPMorgan rightly notes, the realisation that “the major central banks are on sabbatical into 2020” is pushing down bond yields, amplifying moves in debt markets, particularly in America, the world’s most liquid bond market.

Investors should not be intimidated by a bond market whose signalling power says more about the actions of global central banks than it does about the direction of America’s economy.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory