Have we really entered a new age of a perpetual bull market for stocks? The current rally in the S&P 500 is the longest on record, with another high notched up last week. Will the

central banks finally spoil the party or will they continue to lead the rally as they have since the darkest days of the 2008 crash? With global monetary policy becoming blurred, investors can probably count on the central banks to extend their blessings a while longer.

It’s a far cry from 1996 when then United States Federal Reserve chair Alan Greenspan railed against overvalued stock markets, warning of the dangers of “

irrational exuberance” unduly ramping up asset values relative to risk. These days, it seems just as important for central bankers to keep a keen eye on stock market performance as to do their usual job of helping maintain the best conditions for sustainable, non-inflationary economic growth and job creation.

The central banks did a great job of building the rally out of the debris of the crash, by plying the global economy with endless supplies of

easy money, cheap credit and institutional support. This was aimed at rescuing hard-pressed consumers, businesses and financial markets from the brink of disaster, but it ended up providing an unparalleled windfall for global investors, laying the foundation for a 333 per cent rally in the S&P 500 since the post-crash lows 10 years ago.

Which begs the question: what should the central banks be doing now? The world economy is back on its feet, with global growth expected at

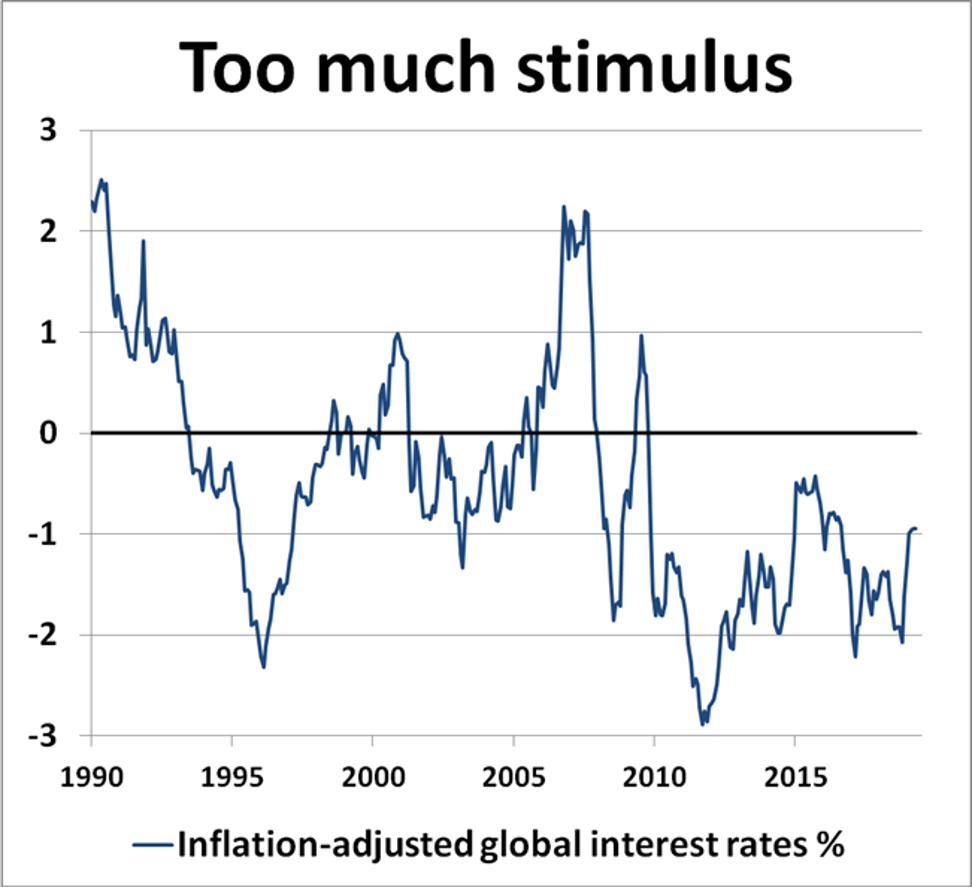

3.3 per cent this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. Does it still warrant global interest rates running at low, super-stimulus levels? Should robust economic recovery coupled with 2 per cent inflation be the main priority, or is it more important to keep global markets fired up on cheap and easy money?

At a time when prudential monetary management should be the dominant theme, central banks have ended up dancing to the stock market’s tune. Economic, consumer and business confidence is so closely linked to stock market sentiment that policymakers seem reluctant to rock the boat in any way. Investors have become so reliant on the free flow of cheap credit that it will be an uphill struggle to reverse it. In essence, the central banks are aiding and abetting the longest bull market in history.

Global monetary policy is marooned. The Fed has

stalled interest rate tightening, emphasising patience, which is nothing more than a euphemism for sitting on the fence. The

European Central Bank is in the same boat, stranded on future rate policy. Meanwhile, the People’s Bank of China shows no inclination to tighten or loosen policy either way. Conflicted growth and inflation data may be to blame, but there is also a tacit need for global policymakers to maintain a steady calm for markets.

The problem is unlikely to be resolved in the short term. The central banks are on the defensive and steering away from policies which might upset market sensibilities. The Fed tried to move US interest rates back to more neutral levels but gave up in the face of anticipated market reaction. The risk of another “

taper tantrum” has been a sobering influence on tightening intentions more generally.

Markets cannot defy gravity forever and it will be interesting to see how central banks cope when the equity rally finally fizzles out and gloom descends again over global economic confidence. Although critics believe that central banks have run out of rope, there are still options to fall back on.

Official interest rates can be eased again, quantitative easing programmes can be rebooted and market liquidity provisions boosted to meet new needs. The Fed has a better base to cut interest rates from again. The ECB can push rates deeper into negative territory. The

PBOC has plenty of scope to cut rates, ease bank reserve requirement ratios and add liquidity to promote recovery.

If the world has entered a new age of low interest rates, benign inflation and extended stock market euphoria, it’s a mixed blessing. The challenge for policymakers is easing investors off the highs without triggering another global hard landing.

David Brown is chief executive of New View Economics