Hong Kong must not sacrifice the public interest in deals with landowners

Regina Ip says while public-private partnerships have worked in the past to spur Hong Kong housing development, the circumstances were different. Any deals today with landowners must be 100 per cent transparent, with every sum scrutinised

Watch: Mei Foo Sun Chuen, Hong Kong’s first private housing estate

The land supply task force was right in pointing out in its consultation document that public-private partnership is not entirely new to Hong Kong. It cited the government-business partnership in the development of Sha Tin new town in the 1970s as an example.

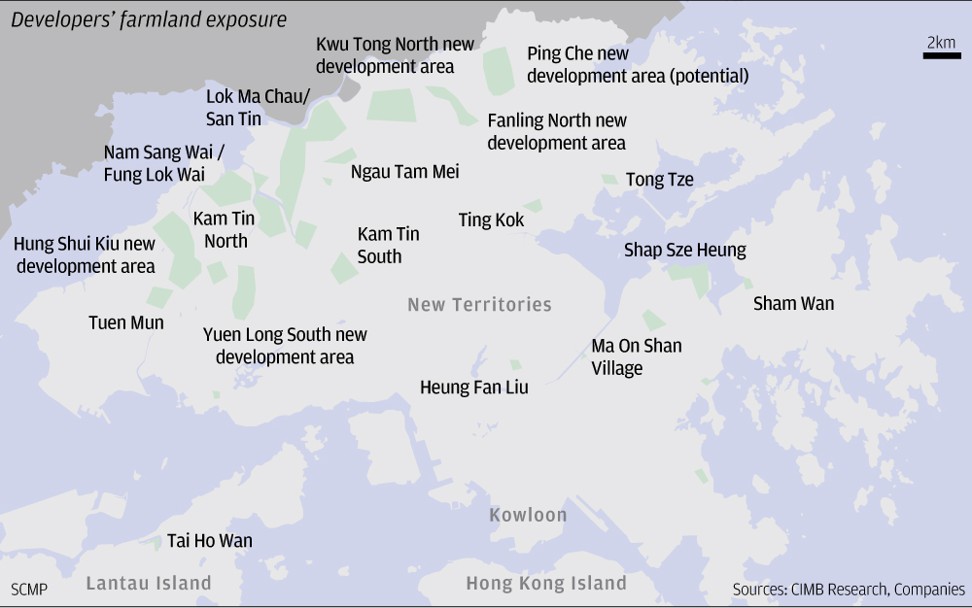

Private developers were invited to form a joint venture to reclaim land to form a site of roughly 56 hectares. Upon completion, 70 per cent of land was passed to the government for the construction of public housing while the remainder was kept by developers for a major private housing estate, City One Shatin. So why not do another deal with developers by rewarding those who would supply land with extra plot ratios or reduced premiums for lease or land use modifications?

Former senior officials involved in the Sha Tin new town development point out, however, that the government-business partnership did not take the form of rewarding developers for the land they gave up. In the 1970s, the developers had no land bank; nor did the government have the hefty fiscal reserves it sits on today.

In accordance with the Sha Tin Outline Zoning Plan approved by the governor in council in 1967, the government invited the developers to reclaim the fish ponds and approved public-private housing distribution on a 70:30 ratio to ensure mixed housing development.

There are no lack of precedents of government rewarding developers with extra plot ratios for building elevated pedestrian walkways or tunnels that benefit the public.

The Land and Development Advisory Committee, chaired by Greg Wong and comprising representatives of professions engaged in real estate development, has been advising the government on “specific development proposals and projects initiated by non-government organisations or private-sector proponents which carry broader economic or social merits”, among other issues. So the government could be forgiven for toying with the idea that this committee could be used to advise on the concessions that could be offered to developers in cutting deals involving the New Territories agricultural land.

Deals involving New Territories land would be of a much grander scale, involving many more billions of dollars, than the projects deliberated on by the Land and Development Advisory Committee. None of the non-official members, including Wong, are “public servants” who are subject to the Prevention of Bribery Ordinance or liable to prosecution for misconduct in public office under the common law.

In working out deals with developers under the rubric of “public-private partnership”, the process must be 100 per cent transparent, so that the public could closely scrutinise whether the balance has been tipped in favour of private-sector proponents. Indeed, given that negotiations with developers have all along been tightly regulated under the law, and the large sums of money involved in mega land deals, any departure from the existing statutory framework risks opening up opportunities for shady deals which would do long-term damage to Hong Kong’s public administration systems.

The government has had the wool pulled over its eyes before, and that could happen again

If developers seek a partnership with government so the latter would help by resuming nearby tso (ancestral) or tong (clan) lands, or by spending large sums on supporting infrastructure, the numbers must be meticulously crunched to ensure that the government, and by extension the public, does not end up getting the short end of the stick.

The government has had the wool pulled over its eyes before, and that could happen again. As the English proverb warns: Beware of Greeks bearing gifts. The government is well advised to beware of the private sector proposing a partnership where it suits them.

Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee is a lawmaker and chairwoman of the New People’s Party