Emerging markets’ dollar flight: the Fed is not to blame, and it knows it

Nicholas Spiro says domestic weaknesses bear the lion’s share of the blame for market turmoil in Argentina, Turkey, Brazil and South Africa, so don’t expect the Fed to adjust the pace of its rate increases to suit them

Every now and again, a prominent policymaker takes the bull by the horns and tackles a hot-button issue in financial markets.

Leaving aside the issue of whether the Fed should heed Patel’s warning, it is refreshing to hear a leading policymaker – especially one from a major developing nation – point out that the Fed’s interest rate policy is not to blame for the sell-off in emerging markets.

If Patel has a culprit in mind, it is Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress, whose reckless fiscal policies risk hoarding dollar liquidity, restricting capital flows to developing nations.

Yet, while Patel is right to argue that the sharp declines in emerging market asset prices have little to do with Fed rate increases – inflows into emerging market bond and equity funds reached a record high of almost US$200 billion last year despite three rate hikes – he fails to mention the role of domestic factors, which are more important than external ones in explaining much of the current selling pressure.

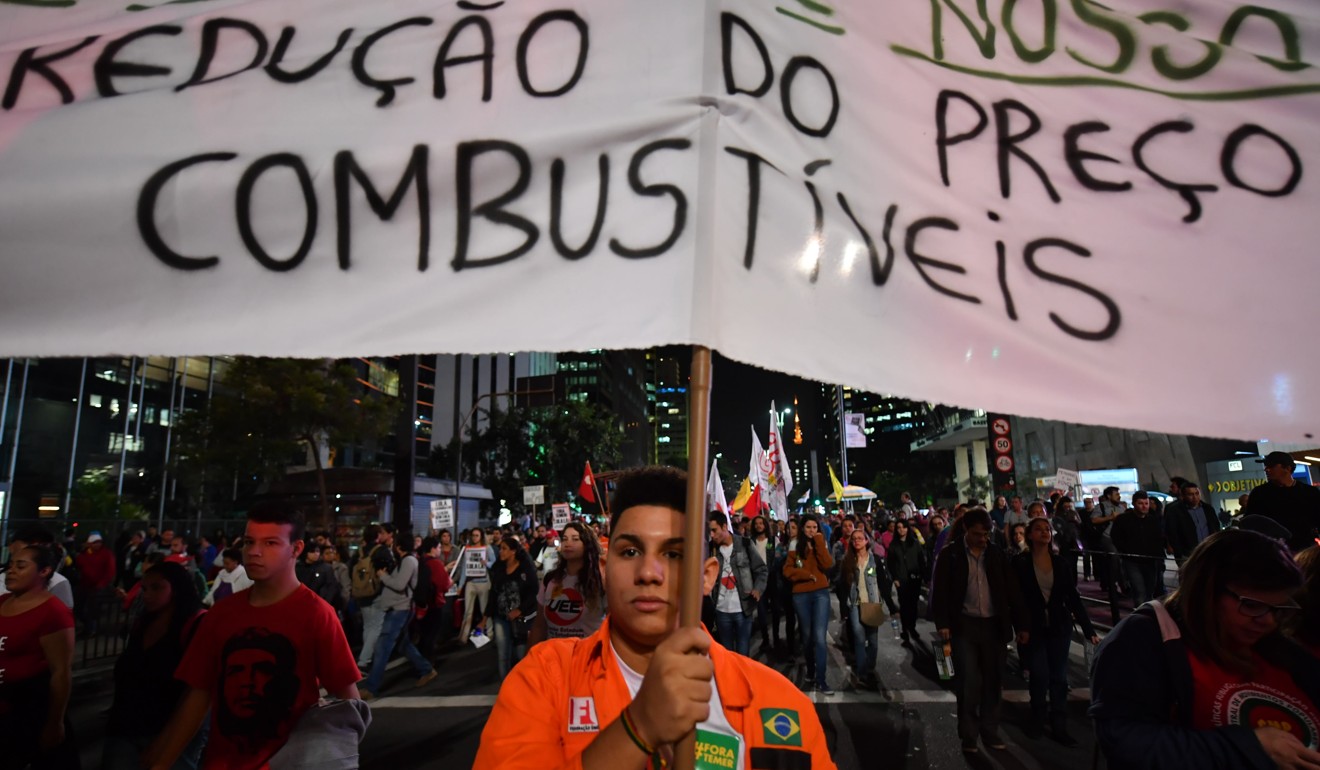

While this year’s surge in the dollar and Treasury yields may have triggered the turmoil in emerging markets, it is the common vulnerabilities in several leading developing economies which account for the bulk of the price declines in the past two months, causing the entire asset class to come under strain.

Moreover, vulnerabilities tend to beget more vulnerabilities, drawing attention to other areas of weakness in emerging markets.

These country-specific weaknesses have become more apparent as financial conditions begin to tighten. They also exonerate the Fed from most of the blame for the current turmoil in emerging markets, making it less likely that America’s central bank will feel compelled to delay the withdrawal of stimulus.

Jerome Powell, the new Fed chair, suggested as much in a speech in Zurich last month when he rightly noted that US monetary policy has not been the most important determinant of capital flows to emerging markets.

So on Wednesday, when the Fed is widely expected to raise rates for the second time this year, it is unlikely that the woes of developing economies will figure prominently in the central bank’s deliberations.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory