How will China walk the tightrope between stimulating growth and the need to rein in debt?

Nicholas Spiro says the recent strains on China’s economy have not entirely spooked investors, but the country has a tough economic balancing act to perform

The renewed nervousness about China’s economy, which stems partly from fears about the impact of a trade war with America, also contributed to a sharp sell-off in the commodity sector, affecting particularly the prices of industrial metals. The Bloomberg Commodity Index, a leading gauge of raw materials prices, has dropped by more than 7 per cent since the end of May.

Yet for a variety of reasons, some of them domestic but most of them external, international investors are downplaying the recent strains on China’s economy and markets, easing some of the pressure on policymakers.

The clearest indication of this lies in the strong performance of global equity markets, particularly US stocks, which suffered steep declines during the previous sell-off. The MSCI World Index, a leading gauge of shares in advanced economies, is up by more than 3.5 per cent over the past three months while the benchmark S&P 500 index has shot up by more than 7 per cent and has recouped nearly all its losses since suffering a correction in early February.

Equity markets remain buoyant partly because global growth is on a much firmer footing than in 2015

Equity markets remain buoyant partly because global growth is on a much firmer footing than in 2015. Monthly purchasing managers’ index (PMI) surveys for the manufacturing and services sectors, which in early 2016 were close to levels that pointed to a contraction in output, reveal that the world economy, although slowing, is expanding at its briskest pace in 3½ years. Data published last Friday showed the US economy grew at an annual rate of 4.1 per cent in the second quarter, its fastest clip since 2014.

During the previous China-led sell-off, the most crowded trade was an overweight position in the dollar, which put further strain on Chinese and emerging market assets.

Watch: Baidu’s AI adventure

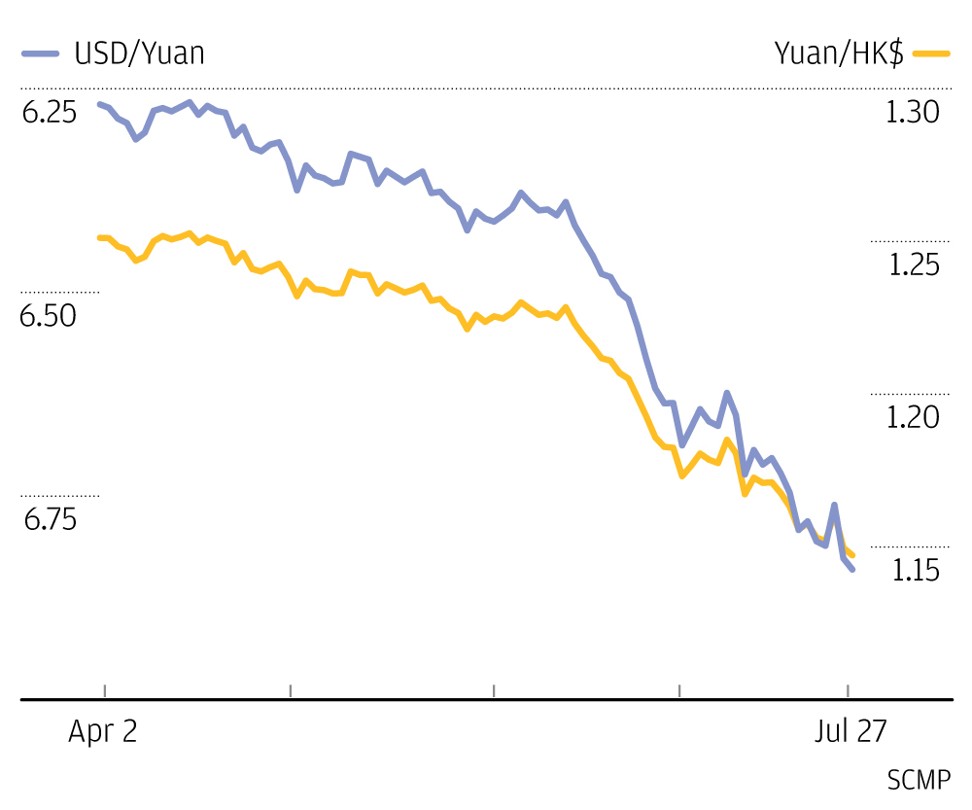

Still, a Chinese stimulus-induced rally carries significant risks, particularly as it is being propelled partly by the depreciation of the renminbi which, if sustained, could lead to the resumption of large capital outflows.

Chinese policymakers are still hoping they can achieve both of these objectives simultaneously. Investors are playing along. How long markets will remain on China’s side, however, is another matter.

Nicholas Spiro is a partner at Lauressa Advisory