Why China and Japan will continue to be frenemies despite Abe’s visit signalling warmer ties

- Cary Huang says trade war has pushed China and Japan closer together, but the Japanese PM’s trip to Beijing did not address countries’ fundamental differences

- Tensions over history, territory, regional ambitions and geopolitical strategy mean the long-term outlook for China-Japan relations remains challenging

China’s rolling out the red carpet to welcome its most “unwelcome” foreign leader, Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, has highlighted the extreme flexibility and pragmatism of Chinese diplomacy.

China-Japan relations have been a roller-coaster ride in the decades since diplomatic ties were established in 1972 – from a golden age marked by friendship that spanned from the 1980s to the mid-1990s, with both Beijing and Tokyo acclaiming their historic bond and geographic proximity, to the recent low under Abe’s watch.

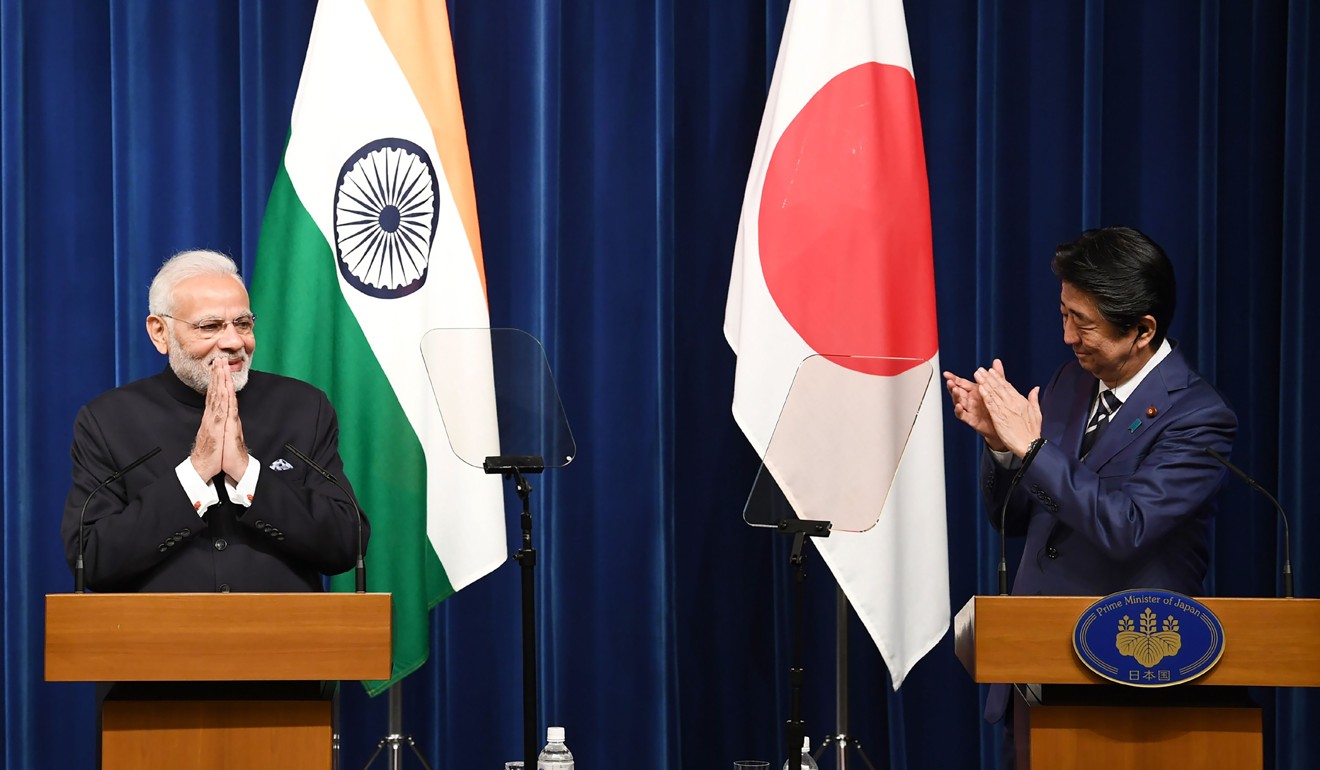

No foreign leader in recent memory has ever received harsher rebukes from the Chinese media than Abe, who was called a “political hooligan” and the “most unwelcome” foreign leader. Abe’s China trip last week was the first by a Japanese prime minister since 2011.

Watch: US-China trade war – 105 days and counting

Although Tokyo and Beijing hailed Abe’s visit as marking a “turning point” in bilateral relations, they failed to address their fundamental disagreement on a series of critical fronts – history, territory, security and geopolitics.

While Abe’s visit gave new momentum to reducing long-standing tensions, the long-term outlook for China-Japan relations remains challenging due to the clash of basic national interests, political views and security strategy.

First, China and Japan’s rivalry for regional dominance and global influence will only intensify amid Beijing’s increasing assertiveness in diplomacy and security policy. For instance, China’s overtaking of Japan as the world’s second-largest economy in 2010 effectively ended the golden years of a relationship in which Japan, as an industrial power, played a critical role in China’s economic modernisation.

Second, both countries are at odds over Japan’s occupation of China during the second world war. With the need for rising nationalism to promote the legitimacy of communist rule, Beijing has frequently used anti-Japanese sentiment to deflect criticism.

Tokyo will not befriend a frenemy at the risk of upsetting its most trustworthy ally

In 2014, Beijing introduced two anti-Japanese public holidays, to mark the Nanjing massacre and Japan’s defeat in the second world war, which exacerbated the ill feeling between the citizens of both countries.

Public opinion surveys conducted in both Japan and China showed an overwhelming number of respondents saying they have a “bad” impression of the other country, sometimes topping 90 per cent mark on both sides.

Watch: How China makes its anti-Japan war dramas

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, China and Japan are political adversaries and strategic rivals due to their conflicting ideological views and geopolitical inclinations. Japan is a member of the US-led global alliance of free democracies and Washington’s key ally in Asia, while China is the world’s last major communist-ruled nation.

Beijing also viewed Japan’s joining of the US and the European Union in pushing back against “non-market economies” as evidence of Tokyo’s attempt to join a US-led alliance of free economies to economically isolate China.

The best hope is that Abe’s trip might inspire restraint from Tokyo in supporting US efforts to isolate China and lead to Beijing backing down from its assertive diplomatic and security posture.

While Abe’s visit might mark a significant improvement in ties, it does not signal a return to the state of relations before the escalation of the Diaoyu Islands dispute in 2012 or to their heyday between the 1980s and mid-1990s. As a direct participant in a turbulent US-China relationship, Tokyo will not befriend a frenemy at the risk of upsetting its most trustworthy ally.

While diplomacy is the trade-off of national interests, sustainable friendship between nations also requires idealism – shared language, sentiments, values and philosophy.

Indian leader Mahatma Gandhi once said, “Relationships are based on four principles: respect, understanding, acceptance and appreciation.” These are exactly what China and Japan lack and sorely need to build a lasting bilateral friendship.

Cary Huang, a senior writer with the South China Morning Post, has been a China affairs columnist since early 1990s