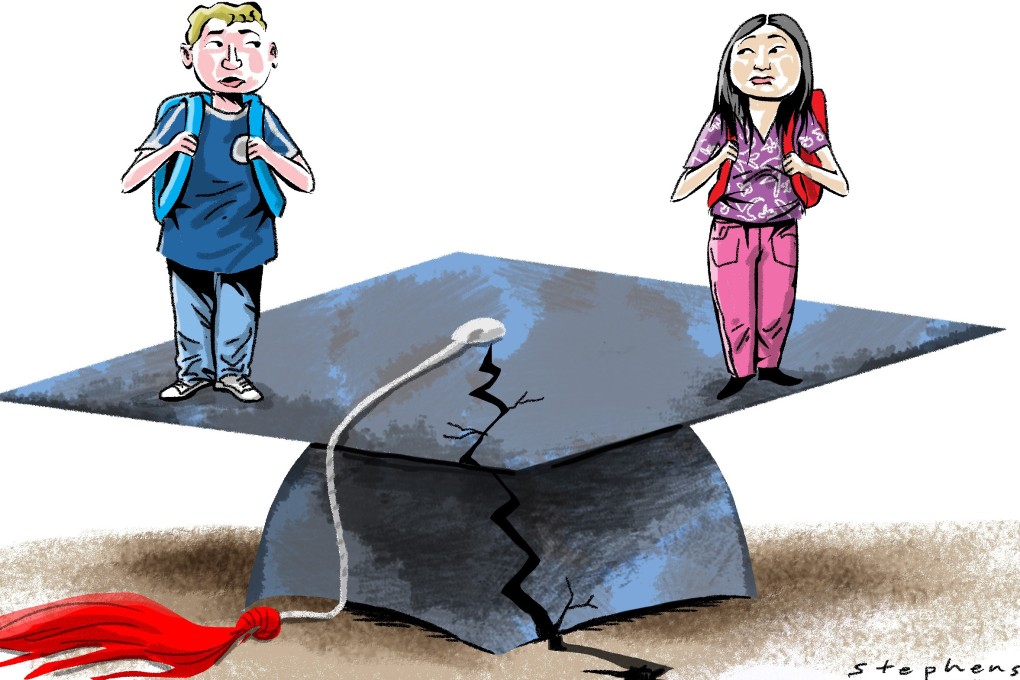

Opinion | How academic progress in China and the West will suffer as a result of growing mistrust

- Universities in the US and elsewhere have responded to growing suspicion of Chinese intentions by cutting joint programmes and restricting Chinese researchers

- It surely won’t be long before China begins to curtail student numbers abroad

Universities in major countries have come to rely on Chinese students for enrolment, dependent to some extent on them to balance budgets and, in some cases, fill empty seats. A significant number of postdoctoral researchers, necessary for staffing research laboratories and who sometimes teach, also come from China. But China’s global higher education role is about to change significantly – with implications for the rest of the world.

One-third of the 1.1 million international students in the US are from China. Similar proportions are found in some of the major receiving countries, such as Australia (38 per cent) and the UK (41 per cent of non-EU students). This has created an unsustainable situation of overdependence.

Within China, several important transformations are taking place. Demographic trends combined with the dramatic expansion of its higher-education system mean there are now more opportunities for study in the country. Billions have been spent upgrading the top 100 or more Chinese universities. Geographically mobile students will find China’s best universities more accessible than ever.