Advertisement

Letters | A few questions about Hong Kong’s historic ‘right of abode’ case

- Twenty years ago, the Court of Final Appeal made its landmark judgment in the ‘right of abode’ case, but its power to overturn existing laws is questionable

Reading Time:2 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

0

Pursuant to the remarks Chief Justice Geoffrey Ma Tao-li made during the opening of the 2019 legal year, that criticism of the courts is always welcome if it is informed or constructive, I would appreciate it if I could be enlightened on why the court can invalidate statutes.

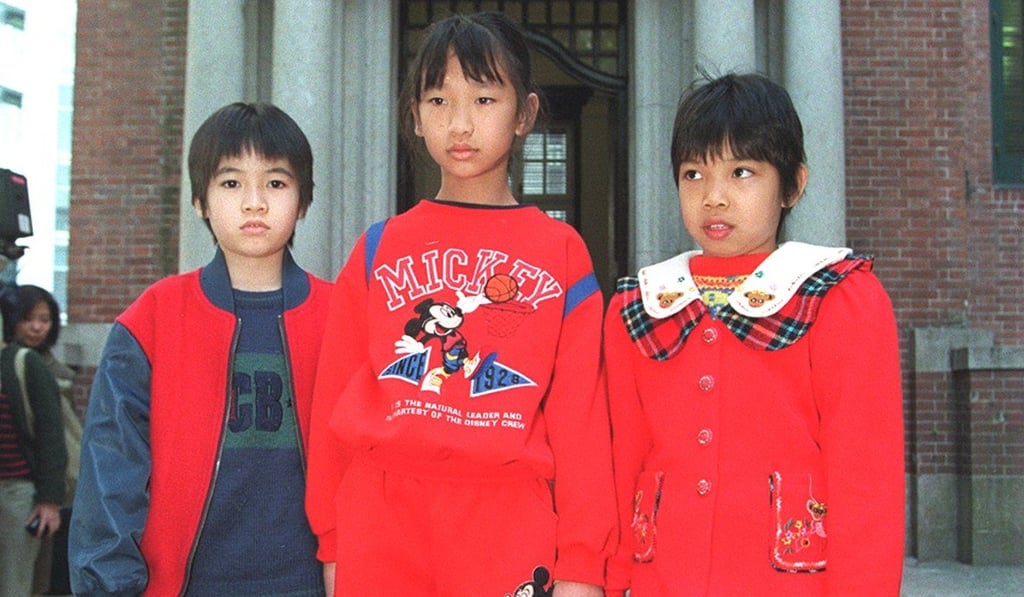

In 1999, in the “right of abode” case (Ng ka-ling vs Director of Immigration), the Court of Final Appeal founded the power to invalidate statutes, after giving an extraordinary interpretation to Article 19(2) of the Basic Law. That article states that the power of the courts in the Hong Kong special administrative region cannot exceed the power the courts had during the colonial era.

Except for the last few years of colonial rule when the 1991 Bill of Rights could be invoked to invalidate statutes considered inconsistent with human rights, the courts in the pre-1997 period had to follow the tradition in England where courts are prohibited from invalidating statutes due to parliamentary supremacy.

The Basic Law, in its Instrument 16, removes the courts’ power to invoke the Bill of Rights to invalidate laws. But, in 1999, the Court of Final Appeal interpreted Article 19(2) in such a way that was contrary to its original purpose, thereby invalidating some provisions of the Immigration (Amendment) Ordinance.

If I am too humble to query the court’s wisdom in interpreting Article 19(2), I turn to common sense. In the 1999 case, the Court of Final Appeal acknowledged it had no power to interpret Article 22 (4) because this article falls under the heading of the relationship between the central government and Hong Kong. Article 19(2) is also under this same heading – why did the court cross the line and interpret Article 19(2) in the first place?

Advertisement