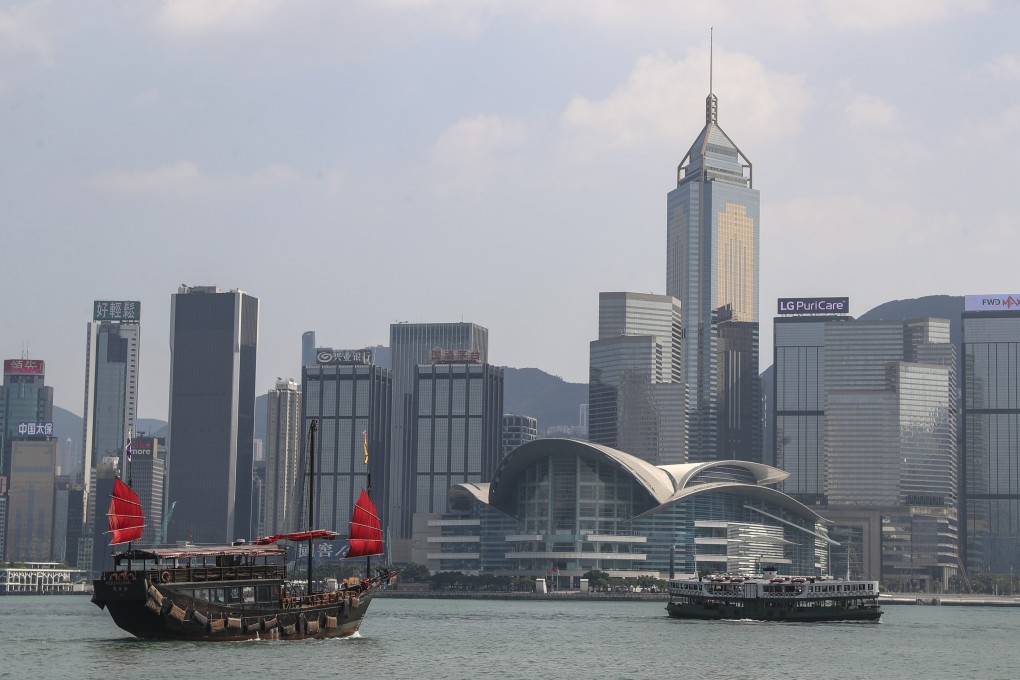

Letters | What Hong Kong can agree on in divided times: the need to protect its uniqueness

- There is consensus that Hong Kong’s uniqueness arises from its amalgamation of the Western system, traditional Chinese society and Lingnan culture. Preserving this would benefit both the city and the nation

I used to work at a local youth think tank, where it was my role as a facilitator to attempt to resolve conflicts across generations and the social spectrum.

While there was diversity in political belief, most people agreed that the uniqueness of Hong Kong arose from the intersection of the Western system, traditional Chinese society and Lingnan culture. Notably, another narrative shared by people from both elite and grass-root communities was that the key to maintaining Hong Kong’s prosperity and competitiveness was to preserve our fundamental system, nothing more, nothing less.

How would pushing for reform help reconciliation in Hong Kong? A dialogue between neoconservatism and neoliberalism, written by mainland scholar Yang Ji-kai, might offer a clue. He points out that reform is the result of incremental change and respect for the historical continuity of traditional values.