Letters | Sex education in Hong Kong: one city, no system

- A flexible school-based approach to sex education results in uneven implementation across Hong Kong classrooms

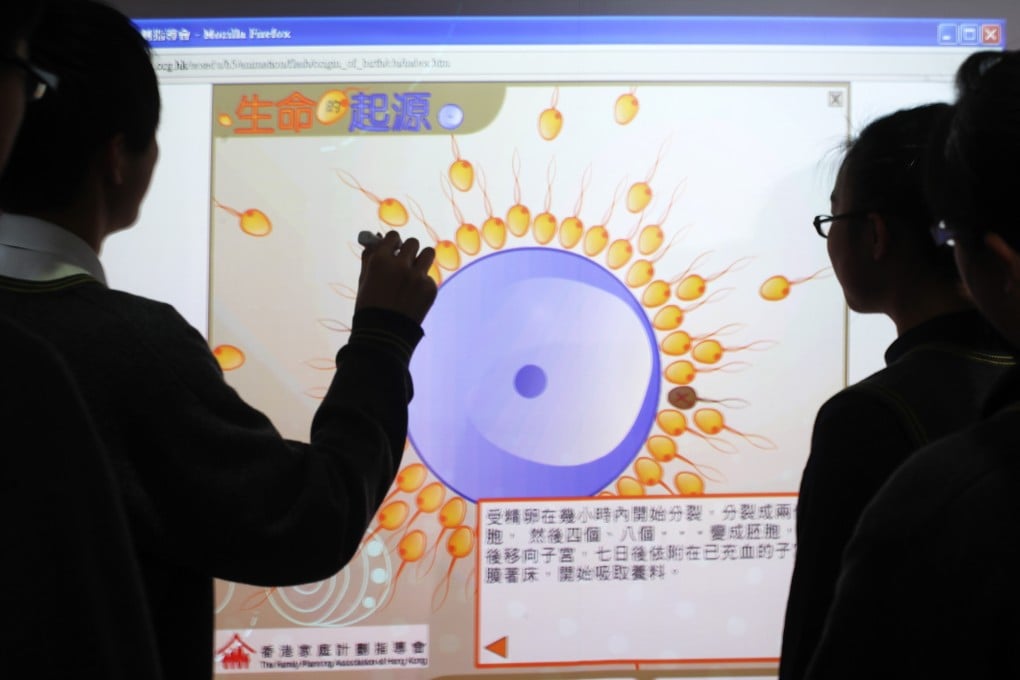

In 1997, Hong Kong’s then Education Department prepared its Guidelines on Sex Education in Schools, focusing on sexuality in the context of relationship responsibilities and a fruitful adult life. The introduction of the guidelines was aimed at inculcating knowledge and values to tackle issues like unlawful sexual intercourse and unwanted pregnancy that had been brought about by inappropriate attitudes and behaviour among the increasingly sexually active younger generation.

Although some schools integrate sex education into their formal cross-curriculum programmes, the dedicated hours and content remain inadequate and scattered as they are subject to the discretion of individual subject teachers who may not have the skills or motivation to impart sex education, especially when academic achievements are prioritised over whole-person development. Moreover, the government is not aware of how effectively sex education is implemented across schools, as it is not rigorously assessed or reviewed.

Some politicians criticise the guidelines as outdated and biased, and having led to the stagnant development of sex education here. Many attempts at sex education have failed to equip students with the necessary knowledge and moral attitudes in an evolving world of technology and sexual mores. Nonetheless, the government regards the guidelines as a historical document, and sees no need to introduce sex education as a mandatory and independent subject, especially when different aspects of it are embedded in key learning areas and school subjects.