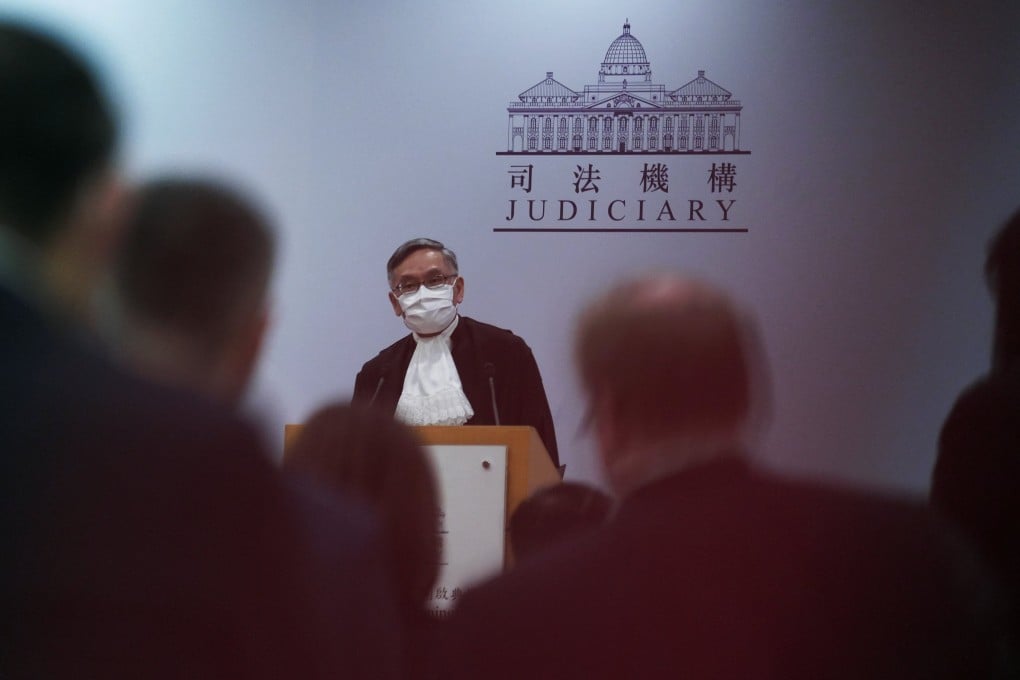

Letters | Two steps the Hong Kong judiciary can take to bolster public trust

- Readers discuss how to make judgments and hearings more accessible to Hongkongers, and what could help the city’s insurance brokers play a greater role in the Greater Bay Area

It is therefore crucial to enhance transparency and efficiency to restore public trust in the judiciary. My humble suggestion is to implement legal bilingualism for court rulings. Upon enactment of the Official Languages Ordinance in 1974, both Chinese and English were declared official languages with equal status. Government documents and those of public bodies are published in both languages, but not judgments.

Since Hong Kong adopts the English common law system, it is somehow more convenient to articulate legal principles in English, yet Chinese is the mother tongue of most Hongkongers. Without a readily available translation, ordinary Hongkongers would have to habitually rely on the press, which has not always been accurate in reporting the court’s reasoning, to understand recent judicial decisions.

Hong Kong should look into the Canadian experience with official bilingualism. All federal courts in Canada are required to render judgments in both English and French. While Canada routinely delivers bilingual judgments to cater to its French-speaking minority, Hong Kong has not catered for its Chinese-speaking majority.

Another recommendation is lifting the blanket ban on filming inside the courtroom, but such activities should remain carefully regulated. The rationale for the ban is to protect witnesses and jurors from intimidation, but neither are involved in appellate hearings of the High Court and the Court of Final Appeal. In recent years, the UK liberalised rules governing cameras in court, which has even been extended to verdict and sentencing, as long as the faces of the jurors are not captured.