Advertisement

Four reasons quantitative easing is not the solution to the global economy’s problems right now

- The damaging effects of the previous rounds of quantitative easing are still being felt in low bond yields, falls in European and US bank shares and increased income inequality

- Further monetary policy loosening might convince investors a recession is imminent while a market rally could encourage Trump in his trade war

3-MIN READ3-MIN

One of the reasons why financial markets had such an abysmal 2018 was the fear among investors that quantitative easing – the extra cash pumped into the financial system by the world’s leading central banks to cope with the fallout from the global financial crisis – was giving way to quantitative tightening.

According to data from Bloomberg, the collective balance sheet of the US Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank (ECB) and the Bank of Japan peaked in March last year and began shrinking in October. As recently as last December, investors were fretting about an excessive tightening in US monetary policy as the Fed – which raised interest rates four times in 2018 – downplayed the dramatic sell-off in stocks and signalled two further interest rate hikes this year.

These worries are now a distant memory. The Fed’s abrupt decision last January to shelve its rate increases because of mounting threats to the global economy sparked a dovish shift in global monetary policy that has gathered steam since US President Donald Trump revived his trade offensive against China last month.

Advertisement

Fed policymakers are dropping heavy hints that rates will be cut if trade tensions intensify – bond markets now anticipate at least two reductions by the end of this year – while the ECB is considering relaunching its quantitative easing programme, which it halted last December.

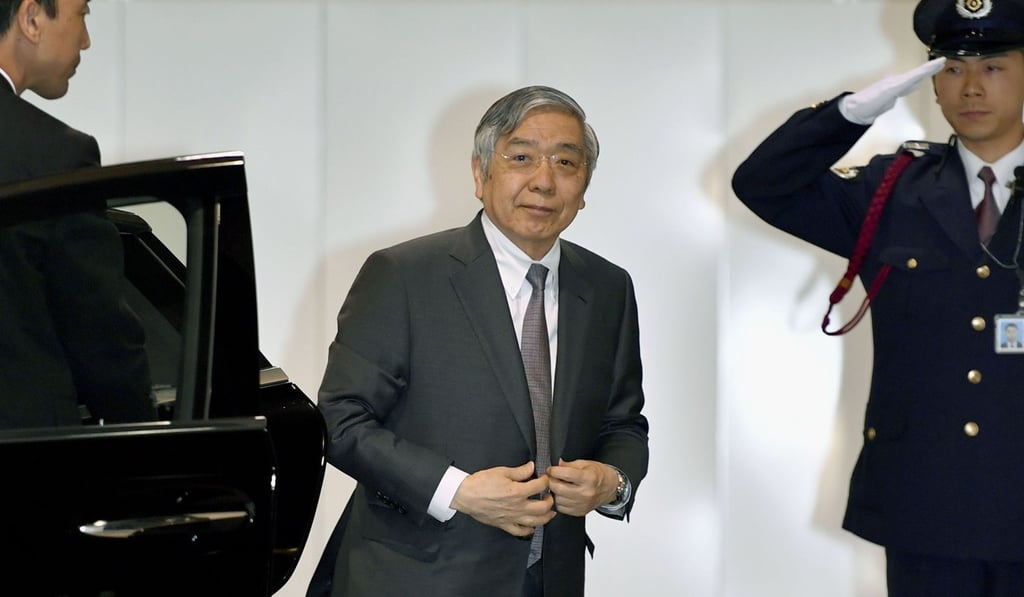

The BOJ, which is still pursuing quantitative easing, has just pledged additional easing measures if inflation falls further below its 2 per cent target. Meanwhile, Australia’s central bank cut rates last week for the first time in three years, partly because of China’s economic slowdown, while several emerging market economies, including Malaysia and the Philippines, have reduced borrowing costs in the past month.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x