Opinion | To win the ‘battle for Hong Kong’, Beijing must stop treating it as just another Chinese city

- Hongkongers will not stand for the routine style of mainland governance. There is enough flexibility in the ‘one country, two systems’ model for peaceful relations, as long as the central government can loosen its grip

Beijing achingly wanted Hong Kong and, more than two decades ago, it got what it wanted. But is it that happy with its prize today? As the saying goes: be careful what you wish for in life, because you might actually get it.

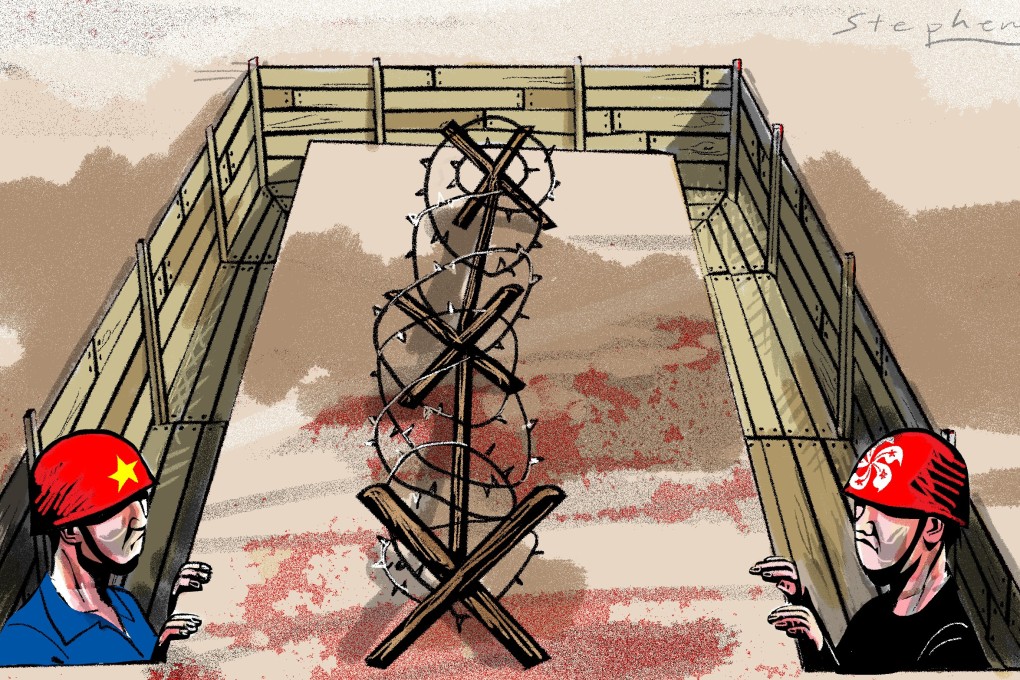

One way or the other, one of the most significant political events in years and potentially one of the most historic will be known as the “Battle for Hong Kong”. And it is anything but played out.

The gut resentment over the perceived entitlement mentality of “snooty” Hongkongers is no secret; there may be more love in Kansas for New Yorkers. Beijing could remind everyone that little Hong Kong contributes to China a world of established cosmopolitanism, not to mention major sector utility in banking and finance. But governing Hong Kong was never going to be a simple matter.