Donald Trump is putting global cooperation to a stress test. And the world may be better for it

- The spirit of international cooperation that emerged from the ashes of World War II is under threat, after decades of global economic growth. As the US abandons multilateralism, will other nations step forward as new spiritual leaders?

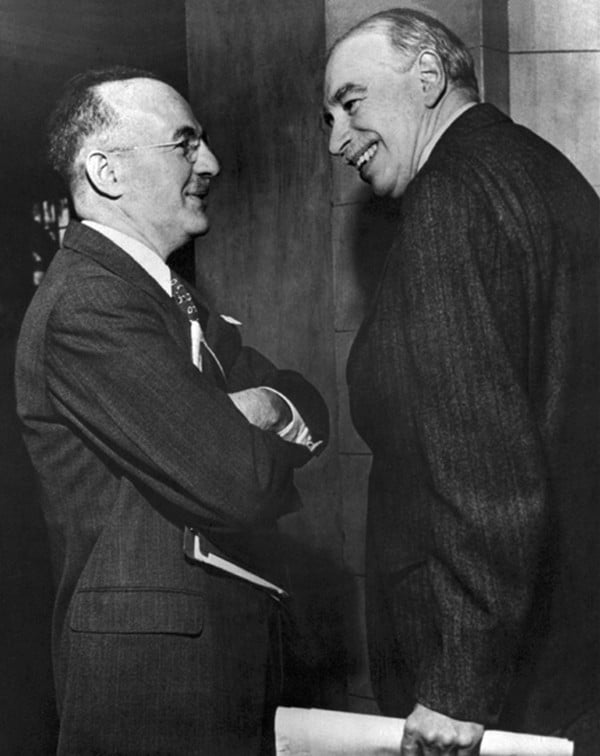

The world was still at war when for three remarkable weeks from July 1 to 22, 1944, deep in the countryside of New Hampshire, US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau and British economist John Maynard Keynes arm-wrestled with representatives from 44 governments over the reconstruction of the entire global economy.

The conference was a precursor to the United Nations (in fact, the meetings at The Mount Washington hotel were formally known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference). It laid the foundations for the Marshall Plan, which was proposed at Harvard two years later by US state secretary George C. Marshall and which provided more than US$12 billion (US$100 billion in present-day dollars) for the post-war reconstruction of Europe.

The spirit of Bretton Woods was clearly expressed as Morgenthau closed the meeting: “We have come to recognise that the wisest and most effective way to protect our national interests is through international cooperation – that is to say, through united effort for the attainment of common goals.”

As Martin Wolf at the Financial Times noted last week, on the back of this cooperation, global income per capita has grown fourfold as the population has grown threefold. World trade has expanded explosively, by 39 times. The share of the world’s population living below the World Bank’s US$2-a-day poverty line has fallen sharply, from 75 per cent in 1950 to 10 per cent in 2015.

Why the West ignores China’s success in poverty reduction

But the US’ abandonment of the spirit of Bretton Woods is particularly harmful to the global economic system, and to international cooperation – at a time when the world needs to work together in battling climate change and managing technological change as well as the financial system’s stresses that have persisted right up to today.

The success of the Bretton Woods institutions has rested not just on a spirit of cooperation, but also on meticulous negotiation and a universal commitment to compromise. It has rested on the trust that agreements, once reached, are lived up to. The erosion of trust after three years of the Trump administration has undermined faith in the willingness of the US, as the architect of the Bretton Woods institutions, to ensure they continue to function as successfully as they have for the past 75 years.

As US disentangles multilateral order, Asia and Europe spin new narrative

And the good news is that even as the stress test continues, the great majority of members of the IMF, World Bank and WTO still believe the organisations have delivered, and continue to deliver, net benefits.

From this vantage point, the US is at an important crossroads. As other nations begin to step forward as champions of the multilateralism at the heart of a globally interconnected economy, is the US’ spiritual leadership set to decline? Will new leadership come from the European Union, Japan – or even China?

The lessons of the past 75 years tell us that Morgenthau and Keynes were right, and that Trump and his acolytes are wrong. International cooperation is still the most effective way to protect our respective national interests.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view