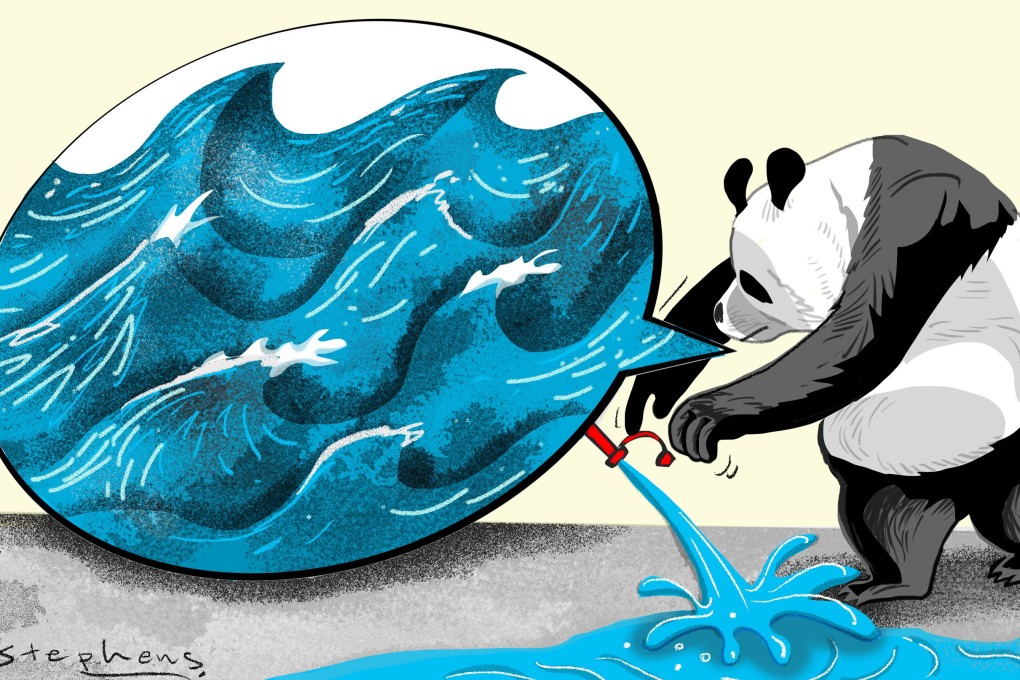

Opinion | To prevail over the US in the South China Sea, Beijing must be less ambiguous and more diplomatic

- Many of China’s claims to the South China Sea are defensible, but its spokespersons have been too vague in stating and defending them

- Beijing must learn to win by persuasion, and refine its claims so they are compatible with the international order

In 1954, when Zhou Enlai was both premier and foreign minister of the new China, he famously put his spin on Clausewitz’s dictum on war and said: “All diplomacy is a continuation of war by other means.”

Given that China is engaged in a long-term struggle with others for control of the South China Sea, it needs to greatly improve its relevant public diplomacy in both tenor and tone. Although many of China’s criticised positions are actually defensible, its public relations spokespersons are vague in stating its claims and defending them. This needs to be corrected.

But China’s Foreign Ministry spokesperson Geng Shuang’s response was over the top. He declared: “The so-called award of the South China Sea arbitration is illegal, null and void and we have long made it clear that China neither accepts nor recognises it. The Chinese side firmly opposes any country, organisation or individual using the invalid arbitration award to hurt China's interests.”

Moreover, it drew unnecessary attention to China’s controversial refusal to accept the verdict of a tribunal set up under a treaty to which it is a party. This just played right into the American narrative that China is defying the existing international order and bent on bullying the region into submission.