If Britain’s grand post-Brexit budget doesn’t add up, markets may be in for a rough ride

- Boris Johnson is clearing the decks for a massive public spending binge to revitalise the economy. The cornerstone is a rail project that is running over budget and might involve the Chinese. Markets are wondering who will pick up the tab

Trade barriers will go up, the cost of doing business in Europe will rise for British firms and bilateral trade flows will decline, a no-win situation for both sides. It’s no wonder expectations are so downbeat for the British and European economies in the next few years.

Forecasts from the International Monetary Fund and the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development suggest Britain could be bogged down by years of economic stagnation, with growth averaging little more than 1 per cent per annum for the next few years.

Johnson’s post-Brexit Global Britain sounds good, but that’s about it

Johnson is harking back to a time when Britain’s industrial revolution was forged on the back of an explosive railway boom. He’s clearly hoping history will repeat itself.

It’s a shrewd move because Sunak will be rubber-stamping spending plans, while his family connections to the Indian IT industry could have positive spin-offs in trade relations between Britain and India.

Britain ignored US on Huawei. Canada can do same with Meng

It looks good on paper, but do the sums add up? Johnson is spending money like water and markets are quite rightly asking who will pick up the tab. Higher taxes are generally ruled out by Conservative Party orthodoxy so extra government borrowing has to bridge the gap.

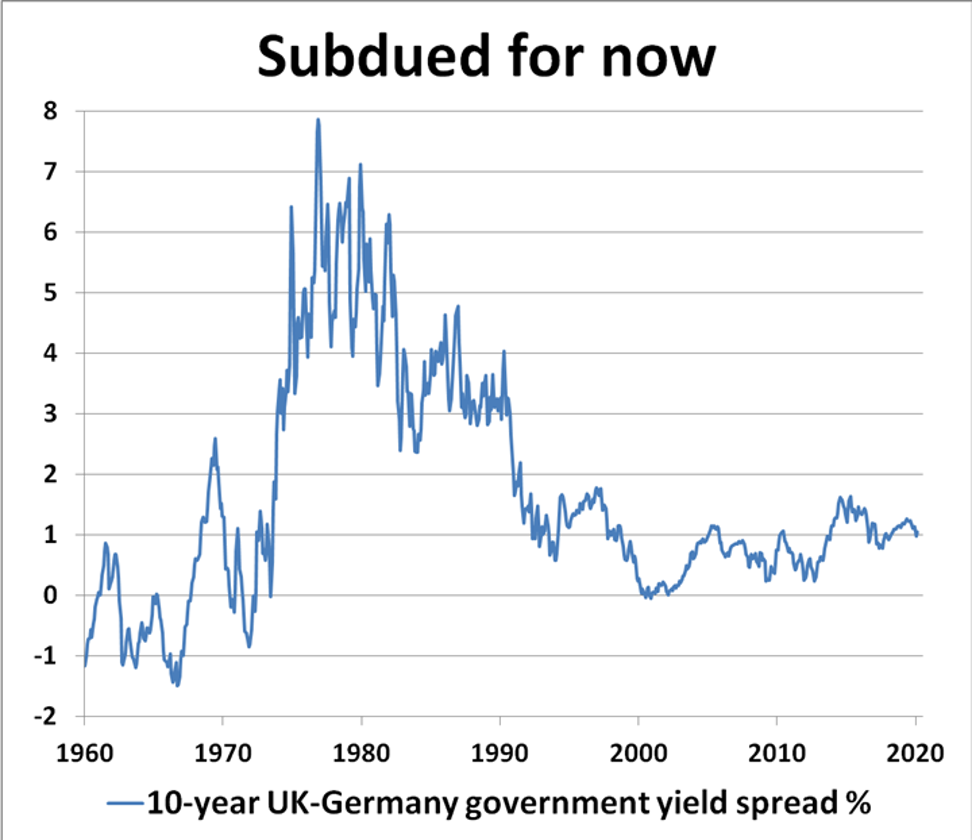

Painful austerity cutbacks reduced the British government’s deficit from 10.3 per cent of GDP in 2009 to around 2.5 per cent last year, but future widening looks more likely now. Stronger growth should be good for British stocks and the pound, but it will come at the cost of increased bond issuance, higher debt yields and rising short-term interest rates.

Johnson’s vision for Britain’s future is a bold one. If he wants an economic renaissance, it’s going to take a lot of money, ingenuity and time. The worry is that this is a pipe dream and next month’s budget could be a rude awakening for taxpayers, investors and markets.

David Brown is chief executive of New View Economics