US paranoia over Chinese heads of UN bodies fails to recognise China’s genuine desire for international engagement

- The American push against China’s candidate for the top job at the World Intellectual Property Organisation betrayed US disquiet over Chinese influence in international organisations

- China, however, sees this as part of its re-engagement with the international community and has worked hard to learn and comply with regulations

Wipo is one of at least 15 massive agencies set up by Western powers when the ashes of World War II were still warm, which set the rules for a range of economic activity. These United Nations-affiliated organisations include the World Bank, the International Monetary Fund, the World Trade Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), the International Civil Aviation Authority, the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) and the International Labour Organisation, Interpol and the International Court of Justice.

The UN’s revenue, which goes towards running these organisations and other programmes, was US$53 billion in 2017, with most funding coming from the UN’s 193 members. Wipo is an exception in that most of its funds come from the money companies pay to have their new ideas patented.

From the UN’s origins, Washington has taken a close interest in the family of UN organisations. Their regulations were largely moulded around a US model and the US provided most of their funding – about 22 per cent in 2017.

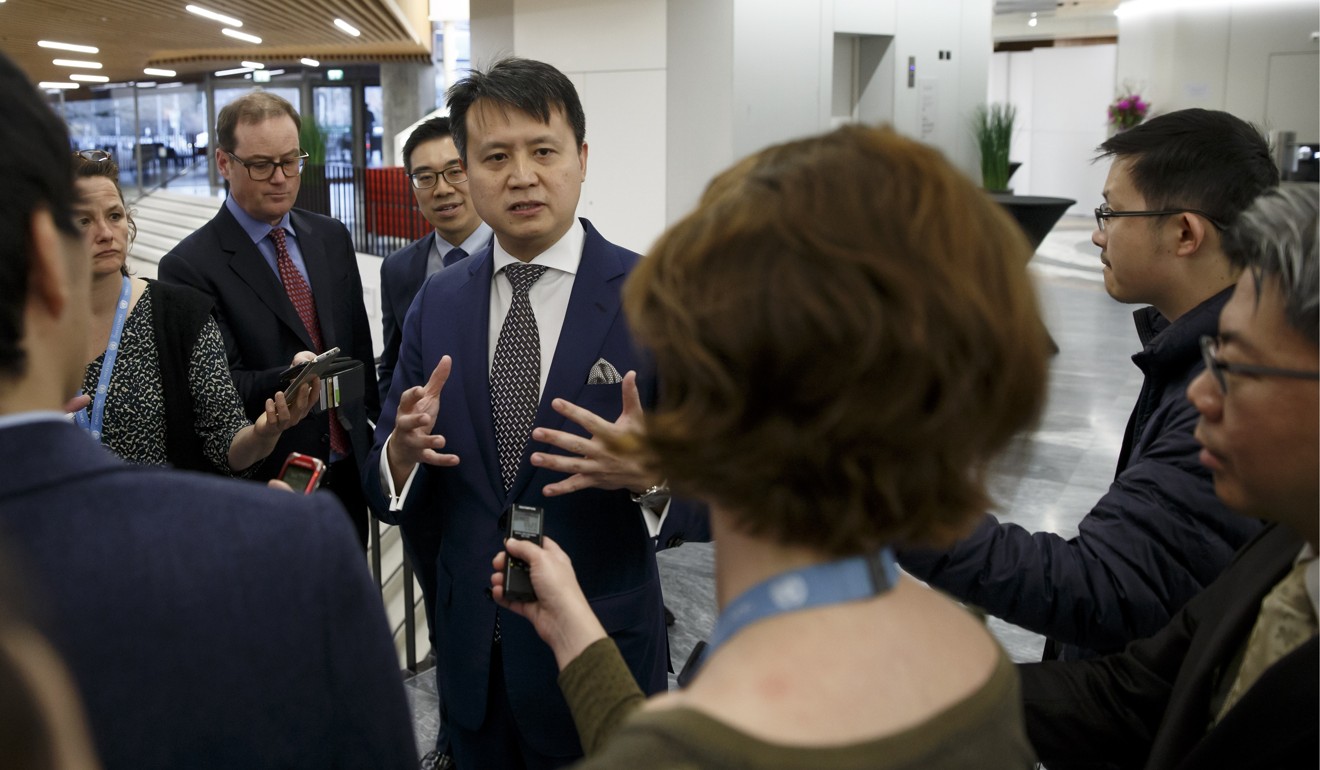

Fevered imaginations in Washington predicted that China would exploit Wang’s leadership to gain access to patent applications before they were published or to alter global IP rules in its favour.

There were also some better founded concerns. China already heads four UN agencies – the FAO, the ITU, the UN Industrial Development Organisation and the International Civil Aviation Organisation. No other UN member holds more than one leadership position among the UN’s 15 specialised agencies that deal with economic activity. Some believe China is making a grab for control of the world’s key regulatory institutions.

Whatever some in the US think about China’s agenda to reshape the world economy in its image by gaining control of its regulatory institutions, I hold a different view. Despite efforts at IP theft in the early decades of China’s re-engagement with the global economy, its behaviour in the past two decades has changed, largely under German tutelage.

Second, since it had played no part in setting the post-war regulations, Beijing believed learning the West’s rules and regulations as quickly and comprehensively as possible was an essential step to re-engagement. Getting engaged in regulatory organisations was part of this effort.

It is true that there could be no better way of subverting and controlling the global economy than by capturing its main regulatory bodies, and there are paranoid souls who believe this is Beijing’s intent. But the evidence of Beijing’s engagement over the past decades contradicts this. Chinese officials have learned the West’s rules well and have reinforced their application, even in sensitive areas like telecoms and technology standards.

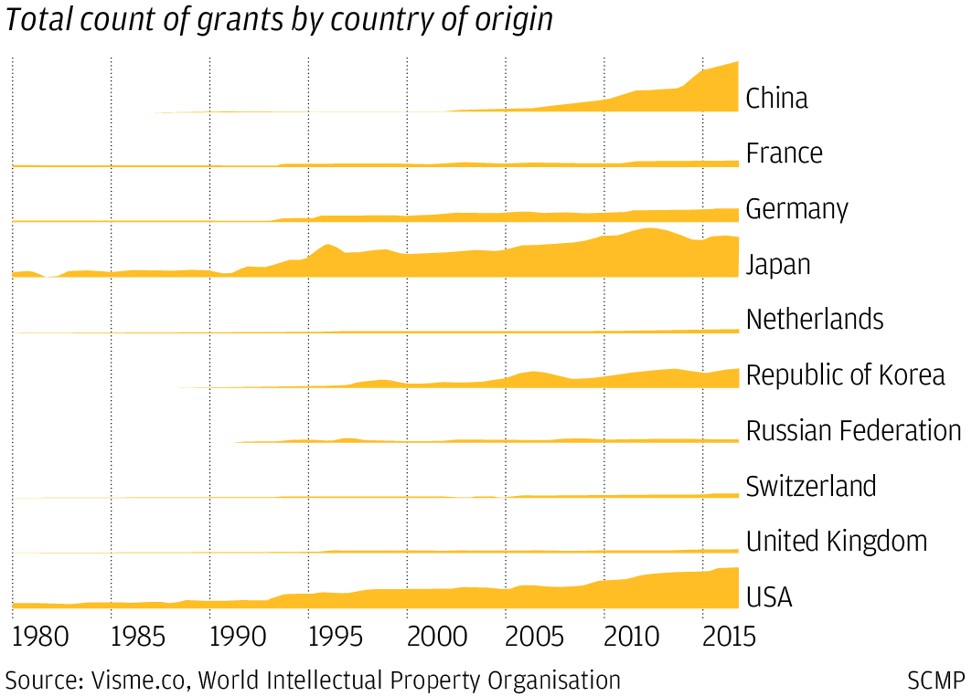

As Chinese companies have become progressively smarter at generating bright new patentable ideas, it should be no surprise that China wants to use Wipo rules and is keen to play a constructive role in developing them.

I am sure Daren Tang will do a fine job as the new Wipo head, but the storm in a teacup surrounding his appointment was paranoid and unneeded. On the bright side, at least it drew attention to some shadowy regulatory agencies that for the past seven decades have played a significant but uncelebrated role in helping us build today’s globally integrated economy.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view