Why US-China decoupling is a dangerous mistake and tantamount to self-harm

- The World Bank expects Covid-19 to impact commodities like oil and platinum, and even the Opec cartel itself

- Its report shows how central China is to commodity trade, and why the US would inflict more harm on itself by decoupling

Over recent weeks, as we obsess daily about the unfolding of the Covid-19 pandemic worldwide and its economic impact, a series of reports from the world’s leading multilateral agencies have shed valuable light on the short-term and long-term implications. None of them make comfortable reading.

Last week, the World Bank joined this symphony of distress with its half-yearly Commodity Markets Outlook, warning that “the impact of Covid-19 has already been larger than most previous events and may lead to long-term shifts in global commodity demand and supply”.

Perhaps inevitably, the report gives priority to the crash in oil and gas prices, which the World Bank authors predict will persist at low levels well into 2021.

The pandemic crash has inflicted much more serious harm on oil than gas, because of the disruption to the transport sector, which accounts for two-thirds of all demand for oil. Natural gas and coal, much more heavily used in the energy sector and domestic heating, have been soft but steadier.

The US in particular faces acute challenges, because the shale oil wells and fracking technologies its oil producers rely on require constant new investments, with each new well needing a price of at least US$48 a barrel to break even.

The World Bank authors believe that air and road transport will be impacted for a long period by the pandemic, reducing demand for cars and therefore transport-related commodities like platinum (40 per cent of global demand comes from catalytic converters in vehicles) and rubber (two-thirds of demand comes from tyre production), whose prices are down about 20 per cent and 25 per cent respectively.

Counselling against the use of import and export controls as a means of ensuring secure supplies of food and medical goods, the report echoes the view of the UN’s Food and Agriculture Organisation, whose chief economist recently asserted that export restrictions are “a mistake” and “will only exacerbate the situation”.

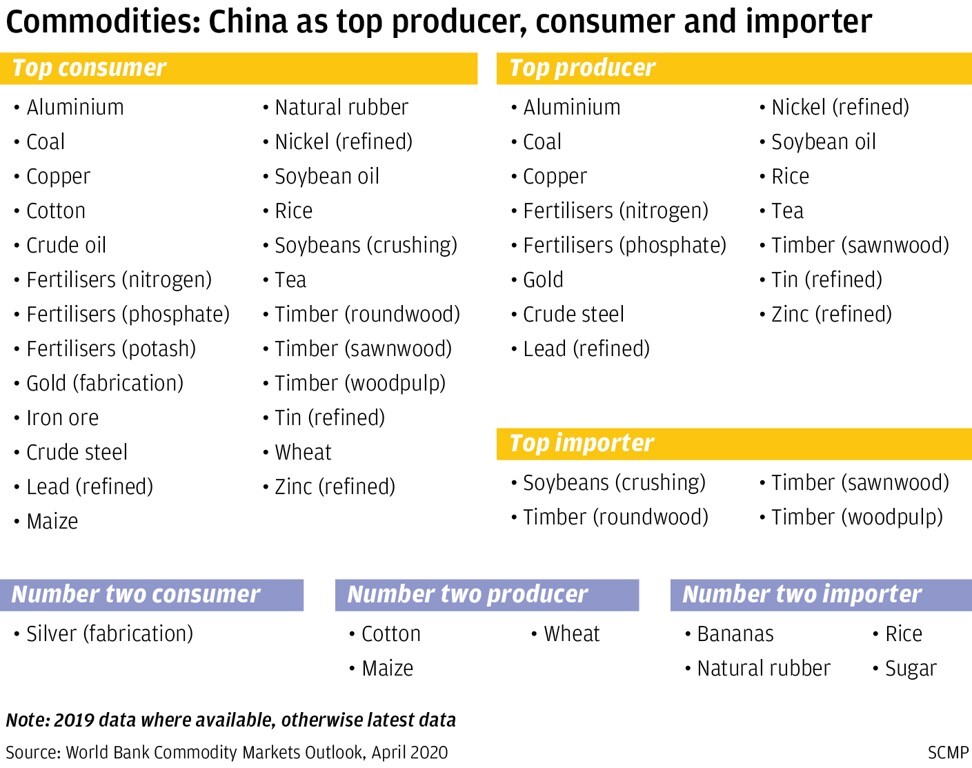

The picture of China’s centrality to the world’s trade in commodities is less clear from the text of the report than from the tables that make up more than half the report. China is the leading source of global demand for the great majority of commodities worldwide, less to underpin export manufacturing than to underpin demand from inside its own huge economy.

Many economies worldwide – particularly those in Africa and Asia that have engaged intensively with China over recent decades – would be excruciatingly conflicted and harmed if forced to make a choice between the US and China.

Perhaps the key lesson from the pandemic for the world’s commodity markets, and the global economy as a whole, is that we are all integrally interconnected, and have been for the better part of the past two centuries. The challenges we face are best tackled together, cooperatively, whether they are a pandemic, climate change or more routine international economic matters.

Let’s hope our leaders have the common sense to recognise this before even more harm is inflicted than already visited on us by Covid-19.

David Dodwell researches and writes about global, regional and Hong Kong challenges from a Hong Kong point of view

Help us understand what you are interested in so that we can improve SCMP and provide a better experience for you. We would like to invite you to take this five-minute survey on how you engage with SCMP and the news.