Advertisement

Inside Out | China must raise its soft power game, especially at a time Trump’s America is losing friends

- Donald ‘America First’ Trump has gifted China an extraordinary diplomatic opportunity, yet Beijing has so far squandered it with its muscular policies in the South China Sea, and on Taiwan and Hong Kong

4-MIN READ4-MIN

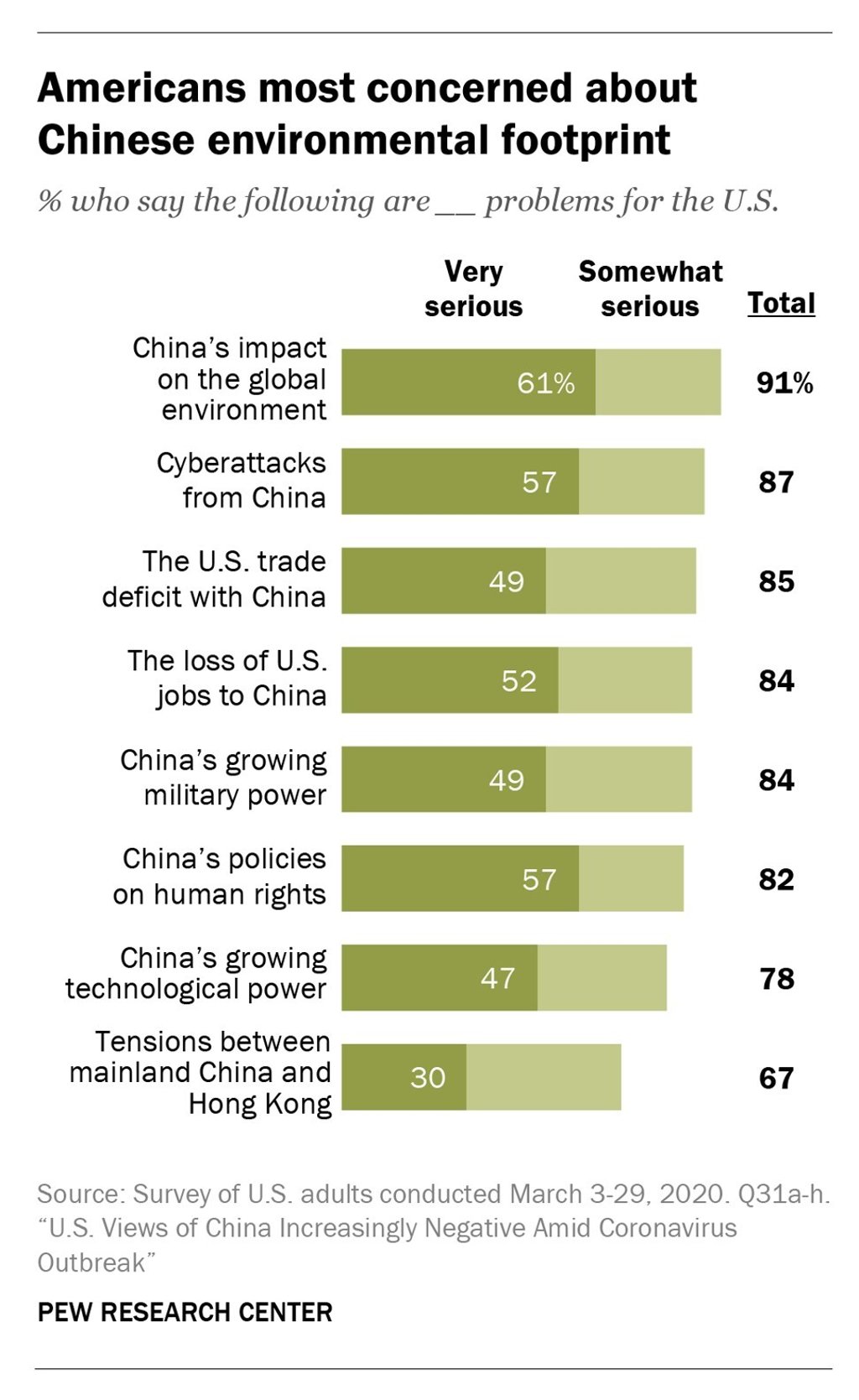

America’s Pew Research Centre is a steady source of fascinating, and often sobering, glimpses into global opinions and trends, so it should be no surprise that its new link-up with Germany’s Korber-Stiftung is already producing interesting work, not least on China.

Research published last week comparing American and German views on China, globalisation and international cooperation showed surprising differences: the number of Germans valuing close relations with the United States tumbled between 2019 and 2020 from 50 per cent to 37 per cent, an obvious casualty of the quixotic aggression of an “America first” White House. At the same time, Germans valuing close relations with China climbed from a meagre 24 per cent to 36 per cent – now equal to those valuing close links with the US. Are we seeing a shift in soft power?

While those in the US seeing globalisation as a good thing wavered at 47 per cent (compared with 44 per cent who believe it is bad), an emphatic 59 per cent of Germans see globalisation as a force for good (versus 30 per cent bad). Over 40 per cent of German respondents to the survey believed that we will emerge from Covid-19 committed to more international cooperation, not less, compared with 35 per cent of Americans.

Advertisement

That such a shift should be occurring at the heart of Europe at a time when the US and China appear to be sliding dangerously towards mutually destructive conflict is fascinating at this extraordinarily bleak time. Can we draw comfort from the fact that even traditionally strong allies of the US are deeply uncomfortable being pushed towards the precipice, and disagree with hardening US views that China constitutes some kind of systemic, existential threat?

Pew research confirms deepening antagonism inside the US towards China – with 66 per cent holding unfavourable views, compared with just 36 per cent in the years after the 2008 financial crash. It also shows mainly unfavourable views on China among the US’s traditional allies: Australia, with 57 per cent, and Britain, with 55 per cent.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x