Outside In | What do Trump’s base, China’s National People’s Congress and Hong Kong’s protest movement have in common? A human tendency towards bias

- Conflicts over race issues in the US and a national security law in Hong Kong are no less distressing for proving what we know – that humans are hard-wired to be biased

- Bias has chance of surviving in a multilateral world of information sharing, cooperation and compromise

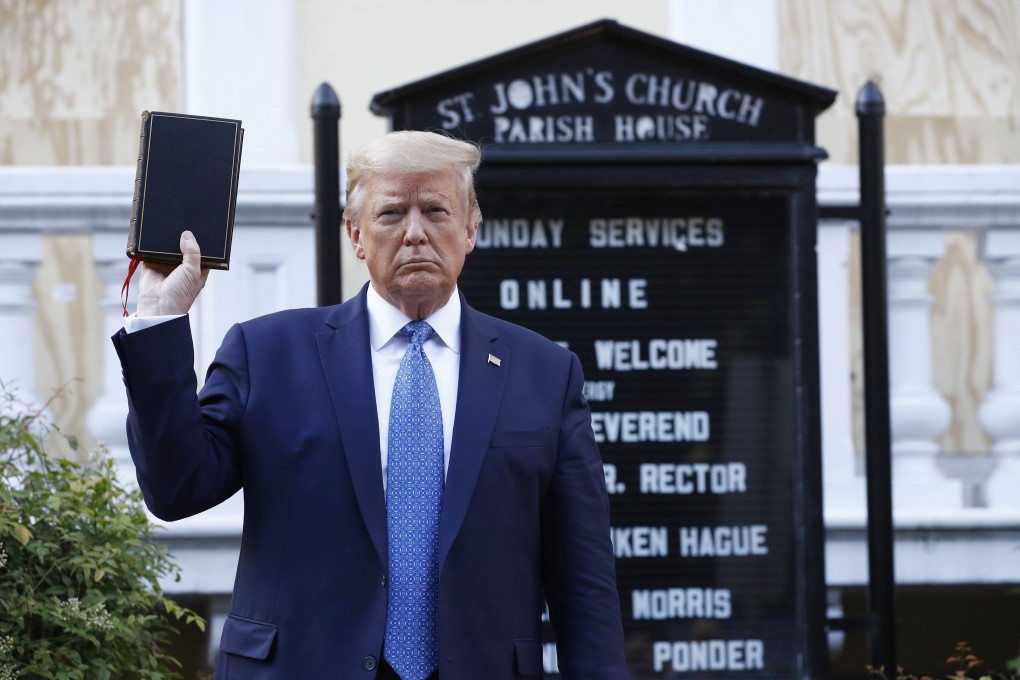

The experience is surreal. How can intelligent, well-educated people watch the same events, absorb the same information, and yet reach such radically opposite conclusions? How can one man’s crisis of police brutality and racial discrimination be another man’s law and order problem?

How can one person claim a steady erosion of personal freedom in Hong Kong since 1997, and another speak with equal conviction about Beijing’s steadfast respect for the autonomy built into Hong Kong’s “one country, two systems”? When relevant evidence remains insufficient, how can so many confidently draw such firm conclusions?

I am reminded of an exploration a couple of years ago by the Financial Times’ Tim Harford of the roots of bias, and how we seem hard-wired for it. Harford said at the time that all of us have a built-in belief that we are seeing the world as it truly is, without bias or error: “This is such a powerful illusion that whenever we meet someone whose views conflict with our own, we instinctively believe we’ve met someone who is deluded.”

Anyone who agrees with us is thinking rationally and “paying attention to facts”, while those who disagree are ignoring important facts, being politically correct, or “seeking peer approval”.

03:56

Unrest spreads across the US fuelled by outrage over police killing of George Floyd

This reminds me of a statement by Bertrand Russell, who a friend pointed me to a couple of days ago: “Man is a rational animal – so at least I have been told. Throughout a long life, I have looked diligently for evidence in favour of this statement, but so far I have not had the good fortune to come across it, though I have searched in many countries spread over three continents.”