Advertisement

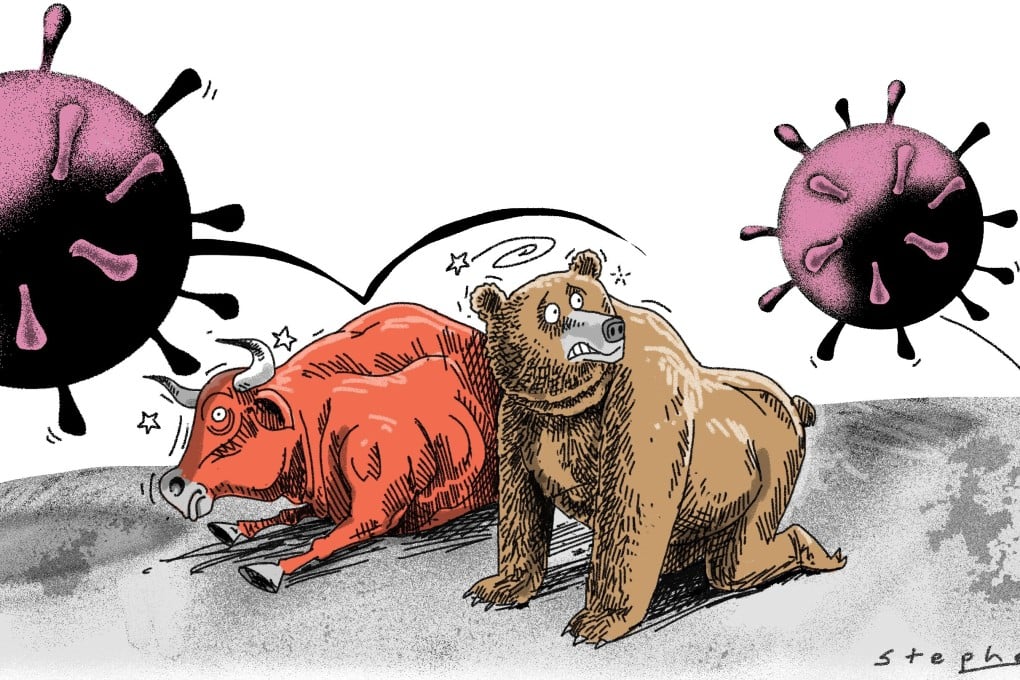

Opinion | Why dreams of easy coronavirus recovery crumble in face of reality

- The first wave of the global pandemic is not yet over but politicians worldwide are declaring victory and rushing to reopen their economies

- Instead of channelling taxpayer money into corporate welfare schemes and bailouts, governments should be sustaining households and small businesses

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

As social restrictions from months of coronavirus isolation ease around the world, there’s growing optimism that perhaps the worst of the Covid-19 pandemic is over. Maybe all this talk of a dreaded global recession was just the fever dream of pessimistic economists.

Hope springs eternal, but it doesn’t pay the bills. If the United States and other countries had actually taken steps to stem the spread of the virus, perhaps employers could resume hiring and consumers would get back to spending.

Half of the world’s 10 largest economies are still trying to get the virus under control – the US, Britain, India, Brazil and Canada. In countries where the virus had been tamped down, including South Korea, new outbreaks have been reported. The first wave isn’t even over and politicians worldwide are declaring victory and rushing to reopen.

Advertisement

Add geopolitical risks to the equation and the situation looks even more grim. The US and China, which together represent roughly 40 per cent of global gross domestic product, are still the twin engines of world growth. They are mired in a trade war, an ideological political battle and increasingly an economic unwinding that will diminish trade and investment for years to come.

04:58

Can globalisation survive coronavirus or will the pandemic kill it?

Can globalisation survive coronavirus or will the pandemic kill it?

Without these two economies growing robustly, the whole world is going to experience a slowdown unlike others in recent history. During the last major recession in 2008-09, China’s economy was still the envy of growth. These days the government is unlikely to even broadcast dwindling economic targets.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x