By painting its contest with China as a ‘good versus evil’ struggle, the US misses the mark

- A recently released study revealing that Chinese citizens’ satisfaction with their government has increased since 2003 sits awkwardly against the US picture of China as a tyrannical state

For many, life feels easier if it is painted in black and white. Choices are easier if they are simply between good and evil. A world of shades of grey is messier, less convenient and tougher to navigate.

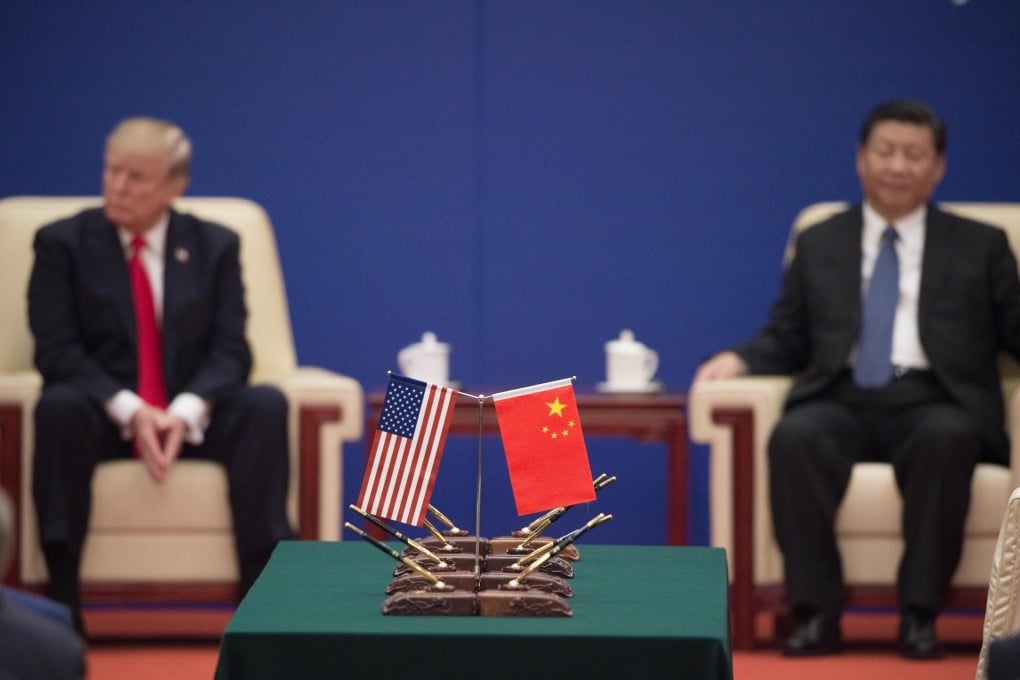

In this vein, US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo last week spoke of the “new tyranny” in China and called for a new alliance of democracies that must choose sides between freedom and tyranny: “If the free world doesn’t change Communist China, Communist China will change us.”

As Pompeo called the free world to arms to fight this “mission of our time” against a ruthless, hegemonic China, I am reminded that this simple “good versus evil” conviction at the heart of the current US administration runs deep and has a long history.

Its roots can be traced back to the Iranian prophet Mani, who around 1,900 years ago developed his Manichaean belief system of a world in constant struggle between the good spiritual world of light and an evil material world of darkness.

This narrative is doubtless seductive in many parts of fundamentalist America, but it sits uncomfortably with the real world. And it conveniently ignores any information or insights that point to a world of many shades of grey.