Advertisement

Opinion | Déjà vu as Carrie Lam backs plan to let Hongkongers on mainland vote in Legco elections

- Any controversy or objection would appear to have been swiftly brushed aside as the chief executive announces broad support for the initiative with little time to waste. Does any of this sound familiar?

3-MIN READ3-MIN

When politicians want to test public reaction to a policy initiative, they sometimes send up a “trial balloon”. The idea is floated in public, often non-attributable, to see if it meets applause or derision. Depending on the reaction, the plan can then be confidently implemented, amended or quietly abandoned.

Earlier this month, the media suddenly filled with stories that Chief Executive Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor was poised to announce that Hong Kong citizens living in southern China might be allowed to vote in the next Legislative Council elections, now postponed to the autumn of 2021. More than 500,000 former Hong Kong residents are thought to live there.

The leak, timed less than a week before the annual policy address was originally due, immediately sparked interest and speculation. There were queries about whether the arrangement would apply only to the Greater Bay Area, or Guangdong province or even all of mainland China. Some wondered if Taiwan would be included.

Advertisement

Once the genie was out of the bottle, the debate moved in many directions. If the principle was that people who held a Hong Kong identity card and maintained links with the city should not lose the right to vote, some argued, then many other places with sizeable Hong Kong communities should be included. If Shenzhen, Dongguan and Guangzhou were in, then why not Toronto, Vancouver and Sydney?

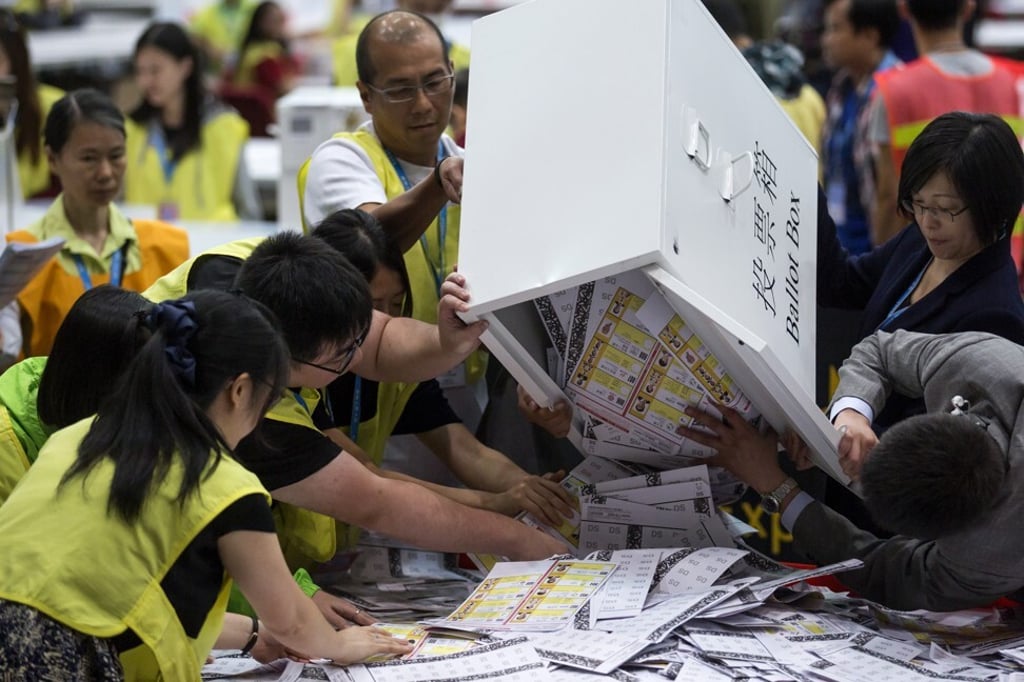

There have also been many comments on purely logistical issues. Among the queries raised were: would ballot boxes be distributed widely outside Hong Kong, and who would be responsible for securing them; would location be restricted to Hong Kong Economic and Trade Offices; would votes be counted in those locations and reported, or would the boxes be escorted back to the city and the votes counted along with those cast locally.

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Select Speed

1.00x