Advertisement

Joe Biden’s push for sustainable trade will be a delicate balancing act

- The president-elect is under pressure from Democratic Party progressives to adopt more stringent policies but must avoid erecting so many barriers for less-developed countries that trade liberalisation is stymied

Reading Time:4 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

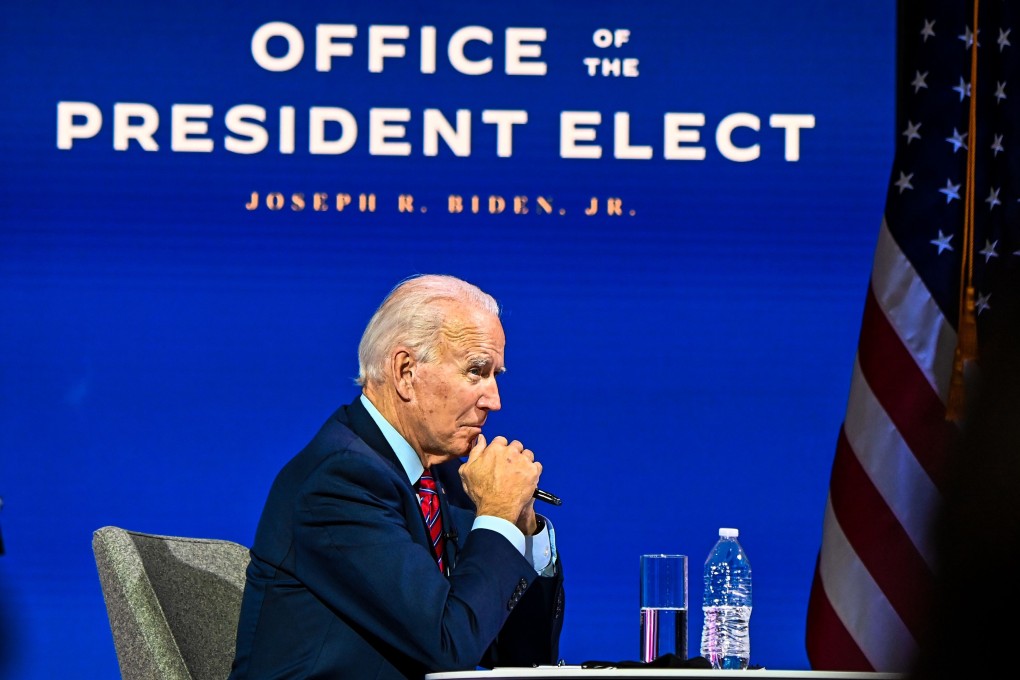

Based on what United States President-elect Joe Biden has said about his approach to trade, and what policies we know his party’s progressive wing will push him to adopt, it is reasonable to wonder: will Biden be the first sustainable trade president?

Sustainable trade stipulates that trade needs to be pursued not only on the basis of economic gains; it must also strengthen social capital – for example, by ensuring high labour standards – and bolster environmental stewardship.

Biden’s position clearly tilts towards greater sustainability in trade policy. He is considering, for instance, imposing a carbon border fee on imports from countries deemed to have insufficiently robust climate policies. The potential scale and scope of what would essentially be a carbon tariff would be an unprecedented fusion of trade and environmental policy.

Advertisement

Biden administration negotiators would also apparently seek to embed emission reduction commitments into trade agreements. Countries that fail to live up to their climate obligations could be subject to trade sanctions. Again, an unprecedented move.

Of potentially greater importance, however, are the more stringent policies Biden will be under pressure to adopt from progressive elements within his party.

04:35

‘Welcome back America’: world leaders react to Joe Biden’s victory in US elections

‘Welcome back America’: world leaders react to Joe Biden’s victory in US elections

There is a battle for pre-eminence within the Democratic Party between the more traditional centrist wing and the energised progressive wing. The desire to defeat Donald Trump was so strong that this battle was suspended to unify behind Biden, who was judged to have the best shot.

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x