Outside In | As China seeks to boost its legal muscle, what should the West expect?

- The good news is that China is keen to continue supporting international institutions, using Western legal rules

- However, law firms currently dominated by US experts must brace themselves for fierce competition ahead

And for Western critics of China, who see the country’s emergence as an existential threat to the US-dominated global balance of power, there is good news, and bad.

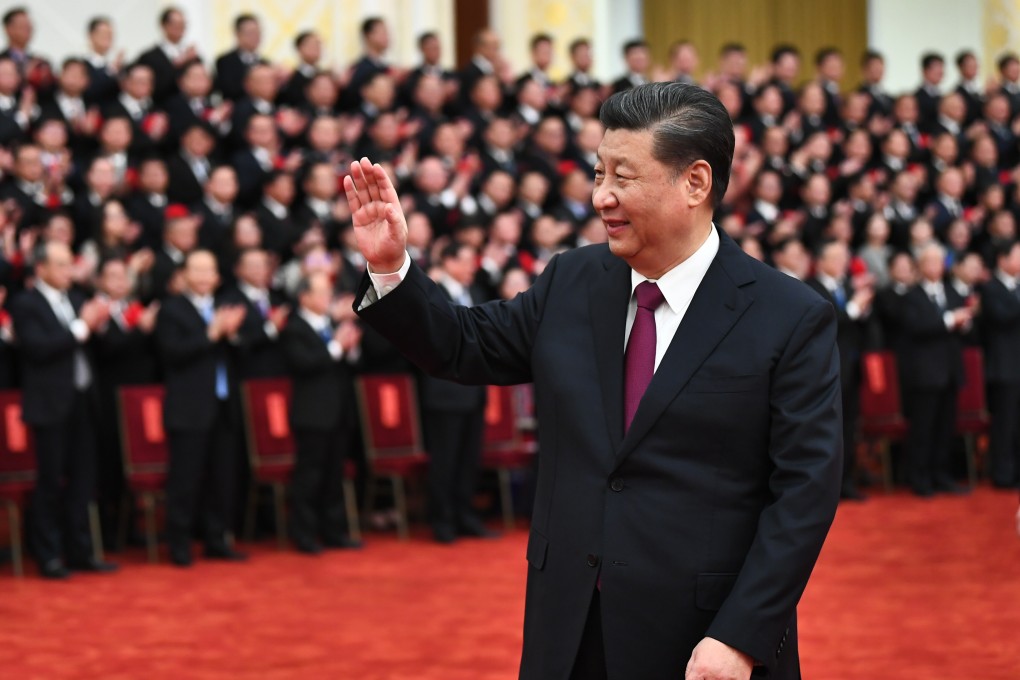

The good news is that Xi’s angst suggests China is keen to continue supporting international institutions, using Western legal rules, rather than subvert the international order with a new legal order of its own making.

The bad news is the same – because when China’s leaders home in on a weakness that they believe is putting in jeopardy their economic growth plans, they do something about it. The law firms so dominated by US legal experts can expect fierce competition ahead.

For sure, Beijing faces massive challenges. International law is predominantly conducted in the English language, and follows the common law rules that are used in the United States, the United Kingdom and former corners of the British colonial empire, leaving even European Union lawyers at a disadvantage.