Advertisement

Macroscope | Climate debate must confront the burning coal issues or risk catastrophic failure

- Big Coal polluters are increasing investment in coal-fired power stations despite public pledges to the contrary

- Vast sums spent on counteracting global warming would be better invested in technology to capture carbon at source, before it enters the atmosphere

Reading Time:3 minutes

Why you can trust SCMP

4

Is the green movement little more than a muddle-headed attempt to solve a problem of a much darker hue whose solution is hiding in plain sight? It is hard to avoid this conclusion once the elephant in the room – coal burning and carbon-belching power stations – is acknowledged.

Climate change has dominated the news this year with International Monetary Fund managing director Kristalina Georgieva calling it “a greater threat” than Covid-19, but few have questioned the notion that green policies and sustainable investment are the best weapons against global warming.

Yet, green policies cannot prevail against black coal, whose role in climate change is coming under increasing scrutiny everywhere from China to Britain. Debate seems certain to intensify and controversy to increase in the run-up to the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in November.

This debate is almost certain to also raise fundamental questions about whether channelling trillions of dollars into green projects and sustainable investment represents the most effective way of tackling climate change.

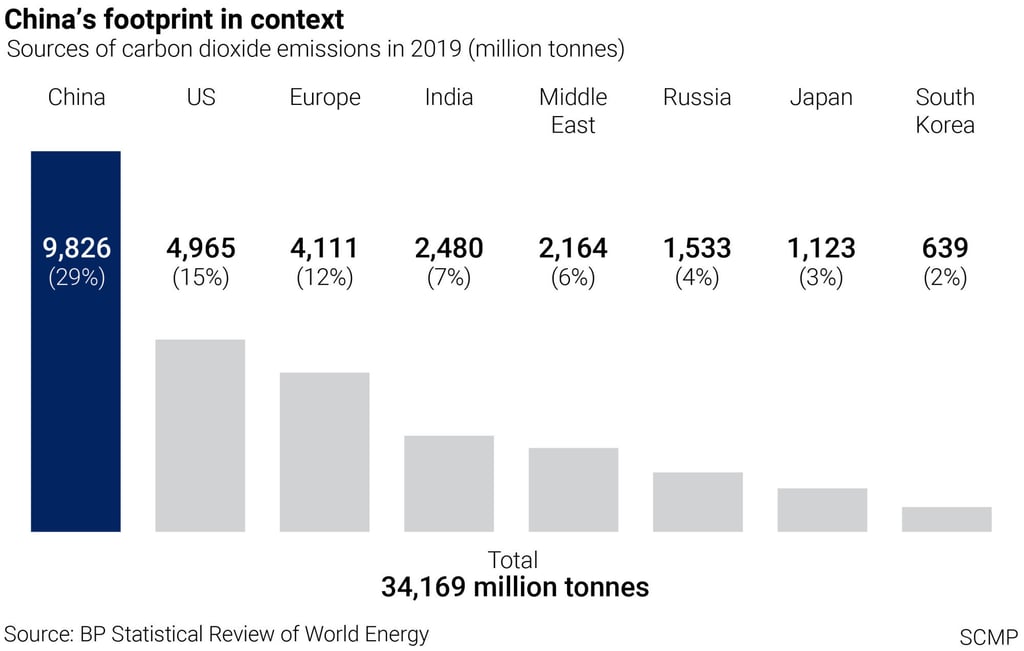

“Coal is a major contributor to pollution and climate change, accounting for 44 per cent of global CO2 emissions,” said the IMF recently, noting that “emerging markets account for 76.8 per cent of global coal consumption, with China contributing about one half”.

Yet, green policies cannot prevail against black coal, whose role in climate change is coming under increasing scrutiny everywhere from China to Britain. Debate seems certain to intensify and controversy to increase in the run-up to the UN Climate Change Conference (COP 26) in November.

This debate is almost certain to also raise fundamental questions about whether channelling trillions of dollars into green projects and sustainable investment represents the most effective way of tackling climate change.

“Coal is a major contributor to pollution and climate change, accounting for 44 per cent of global CO2 emissions,” said the IMF recently, noting that “emerging markets account for 76.8 per cent of global coal consumption, with China contributing about one half”.

China’s intensive use of coal to power its rapid economic growth is also generating debate in and beyond the world’s second-largest economy. This seems certain to spread to other big coal “offenders”, including India, Indonesia, Russia and even the United States and Japan.

Based on his experience as energy minister in a former British government (and his analysis of official and other data), British peer Lord David Howell argues that the world’s biggest polluters are unable or unwilling to meet pledged targets for reducing carbon emissions and global warming.

The essence of his argument is simple but powerful. The Big Coal polluters are increasing, rather than decreasing, their investment in coal-fired power stations and, for valid economic and social reasons, they are set to continue despite public pledges to the contrary.

“The basic problem is that, while 64 countries have been reducing emissions, at least 130 have been increasing them, leading to a worldwide rise when global totals should be falling substantially each year from now on,” Howell said.

Based on his experience as energy minister in a former British government (and his analysis of official and other data), British peer Lord David Howell argues that the world’s biggest polluters are unable or unwilling to meet pledged targets for reducing carbon emissions and global warming.

The essence of his argument is simple but powerful. The Big Coal polluters are increasing, rather than decreasing, their investment in coal-fired power stations and, for valid economic and social reasons, they are set to continue despite public pledges to the contrary.

“The basic problem is that, while 64 countries have been reducing emissions, at least 130 have been increasing them, leading to a worldwide rise when global totals should be falling substantially each year from now on,” Howell said.

Unless we focus on this, catastrophic failure in the climate battle is certain. “The economic shock from Covid-19 produced a drop in global output and a fall in CO2 emissions but they rose 16 per cent in the 10 years to 2019, taking them ever further away from the goals of the Paris Agreement,” he said.

To get back on the Paris path of a rise of no more than 2 degrees Celsius (and ideally 1.5 degrees) above pre-industrial levels by 2050, emissions would have to fall by at least 7.6 per cent a year for over the next 10 years. “This is not going to happen unless realities are faced,” said Howell.

If Howell and others, including the United Nations, International Energy Agency and IMF are right, the social, economic and financial consequences could be of enormous, even existential, importance.

In a nutshell, Howell argues that the green movement, however well-intentioned, is channelling vast sums into measures to counteract global warming when they need to be directed into the equally massive investment in carbon capture.

To get back on the Paris path of a rise of no more than 2 degrees Celsius (and ideally 1.5 degrees) above pre-industrial levels by 2050, emissions would have to fall by at least 7.6 per cent a year for over the next 10 years. “This is not going to happen unless realities are faced,” said Howell.

If Howell and others, including the United Nations, International Energy Agency and IMF are right, the social, economic and financial consequences could be of enormous, even existential, importance.

In a nutshell, Howell argues that the green movement, however well-intentioned, is channelling vast sums into measures to counteract global warming when they need to be directed into the equally massive investment in carbon capture.

Carbon capture involves trapping at source the carbon released by power plants. But the world’s mega polluters are either unable or unwilling to finance the research needed to capture carbon in sufficient quantities.

Something will have to give and it will be the Paris Agreement pledges that these and other major polluters have made, rather than national development targets.

Such warnings have gone largely unheeded and Howell fears this could again be the case at Glasgow COP26, a summit that is the main decision-making body of the UN Climate Change Framework Convention, to which nearly 200 countries belong.

Something will have to give and it will be the Paris Agreement pledges that these and other major polluters have made, rather than national development targets.

Such warnings have gone largely unheeded and Howell fears this could again be the case at Glasgow COP26, a summit that is the main decision-making body of the UN Climate Change Framework Convention, to which nearly 200 countries belong.

The obstacles to phasing out coal are big. “It took the United Kingdom 46 years to reduce coal consumption by 90 per cent from its peak in the 1970s,” the IMF noted. “Across a range of countries, coal use declined just 2.3 per cent annually during the period 1971 to 2017.”

It added that, “coal power plants are long-lived assets with a minimum design lifespan of 30 to 40 years. Once built, coal plants are here to stay unless there are dramatic changes in the costs of renewables or policymakers intervene.”

President Xi Jinping has pledged that China’s carbon emissions will peak before 2030 and the nation will achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. But, as The New York Times noted recently, “sharp debate has risen in China over how aggressively it should cut the use of coal”. That debate will resonate more widely.

Anthony Rowley is a veteran journalist specialising in Asian economic and financial affai

It added that, “coal power plants are long-lived assets with a minimum design lifespan of 30 to 40 years. Once built, coal plants are here to stay unless there are dramatic changes in the costs of renewables or policymakers intervene.”

President Xi Jinping has pledged that China’s carbon emissions will peak before 2030 and the nation will achieve carbon neutrality before 2060. But, as The New York Times noted recently, “sharp debate has risen in China over how aggressively it should cut the use of coal”. That debate will resonate more widely.

Anthony Rowley is a veteran journalist specialising in Asian economic and financial affai

Advertisement

Advertisement

Select Voice

Choose your listening speed

Get through articles 2x faster

1.25x

250 WPM

Slow

Average

Fast

1.25x