How the US Fed’s reassurances on inflation fears are triggering a 1970s flashback

- Now as then, the Fed sees recent increases in the prices of food and other essential goods as transitory, believing they will stabilise with post-pandemic normalisation

- But the biggest parallel may be another policy blunder – as before, the Fed is keeping real interest rates depressed, which in the 1970s only fuelled inflation

They centre on the Fed’s legendary chairman at the time, Arthur F. Burns, who brought a unique perspective to the US central bank as an expert on the business cycle. Yet he lacked an analytical framework to assess the interplay between the real economy and inflation, and how that relationship was connected to monetary policy.

As a data junkie, he was prone to segment the problems he faced as a policymaker, especially the emergence of what would soon become the Great Inflation. He believed price trends were, like business cycles, heavily influenced by idiosyncratic, or exogenous, factors – “noise” that had nothing to do with monetary policy.

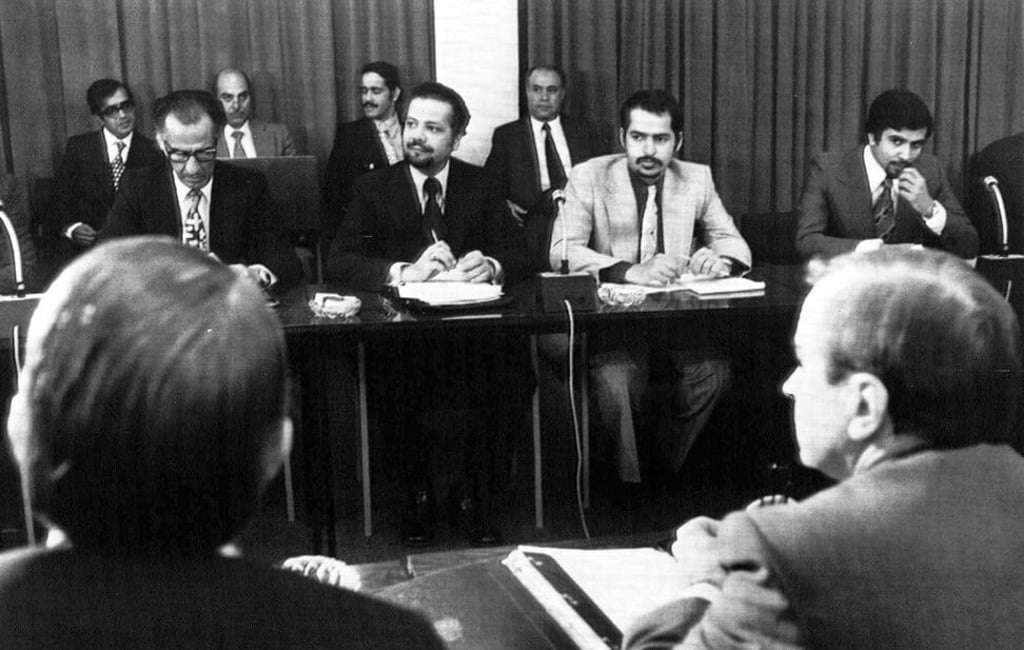

This was a blunder of epic proportions. When US oil prices quadrupled following the Opec oil embargo in 1973, Burns argued that, since this had nothing to do with monetary policy, the Fed should exclude oil and energy-related products (such as home heating oil and electricity) from the consumer price index.

Staff protested, arguing that it made no sense to ignore such important items, especially because they had a weight of over 11 per cent in the consumer price index. Burns was adamant.