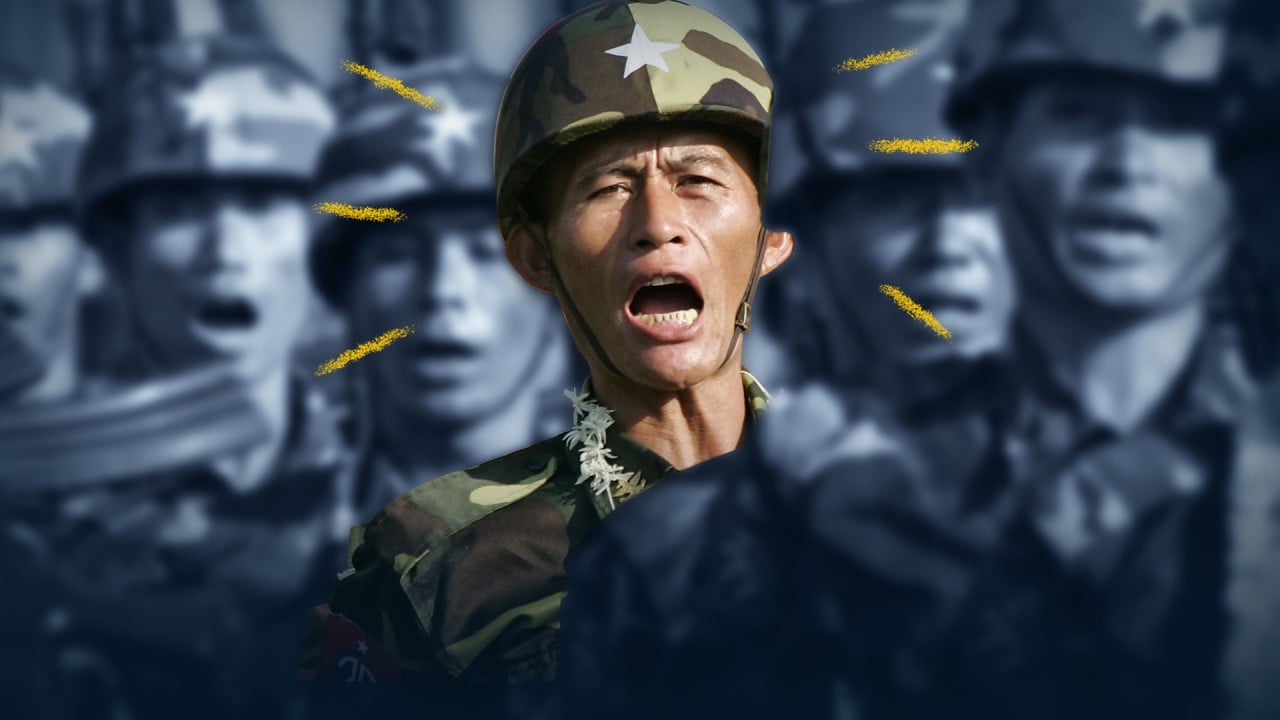

A critical juncture in the China-US contest in Southeast Asia

- Celebrations for the Fourth of July in the US and the Chinese Communist Party’s centenary will intensify the clash of narratives among the competing powers seeking greater regional engagement

- In high-level diplomacy, Covid-19 vaccine supply, infrastructure and trade, China has made much headway

Washington will renew confidence in its democratic values. Beijing will fete the achievements of its governance and economic model. For Southeast Asia, this clash of narratives epitomises the widening gulf between two key partners, and demands more astute hedging.

Even her hastily arranged visits are seen more as an effort to make up for the embarrassing technical glitch at Secretary of State Antony Blinken’s virtual conference with Asean leaders. The cancellation of this year’s Shangri-La Dialogue in Singapore due to the pandemic also foiled US Defence Secretary Lloyd Austin’s debut trip to the region.

Why Biden has been a disappointment to Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia is a major beneficiary of Beijing’s vaccine diplomacy. Millions of donated and government-procured doses from China have gone to the region. Indonesia, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and the Philippines began their mass inoculation programmes using Chinese vaccines.

The higher efficacy rates of US vaccines and high demand for them give Washington avenues to enter the game late. In light of new Covid-19 strains that are more lethal and contagious, US intervention can still make a big difference. For one thing, America can put its surplus vaccine stocks to good use before they expire.

G7 summit shows China is still setting the agenda

Still, the contrast between state-backed finance and private capital could not be starker. China offers flexibility, a greater risk appetite, massive industrial capacity and a growing pipeline of overseas projects. The US and its partners, on the other hand, portray their counter-offer as more sustainable, transparent, and with higher social and environmental standards.

But such an attitude may cede more ground to Beijing. Asean is also wary of the US inclination towards minilaterals as this may undermine its centrality. It is likewise apprehensive about calls for democratic renewal, given the region’s tradition of non-interference in domestic affairs.

With America’s Fourth of July celebrations and the centennial of China’s Communist Party, it is timely for the great powers to review their engagement with the region. Southeast Asia has grown and changed much, and so too should China and the US’ approach to it.

Lucio Blanco Pitlo III is a research fellow at the Asia-Pacific Pathways to Progress Foundation