Opinion | Why Japan should focus on making friends and money, not interfering in Taiwan

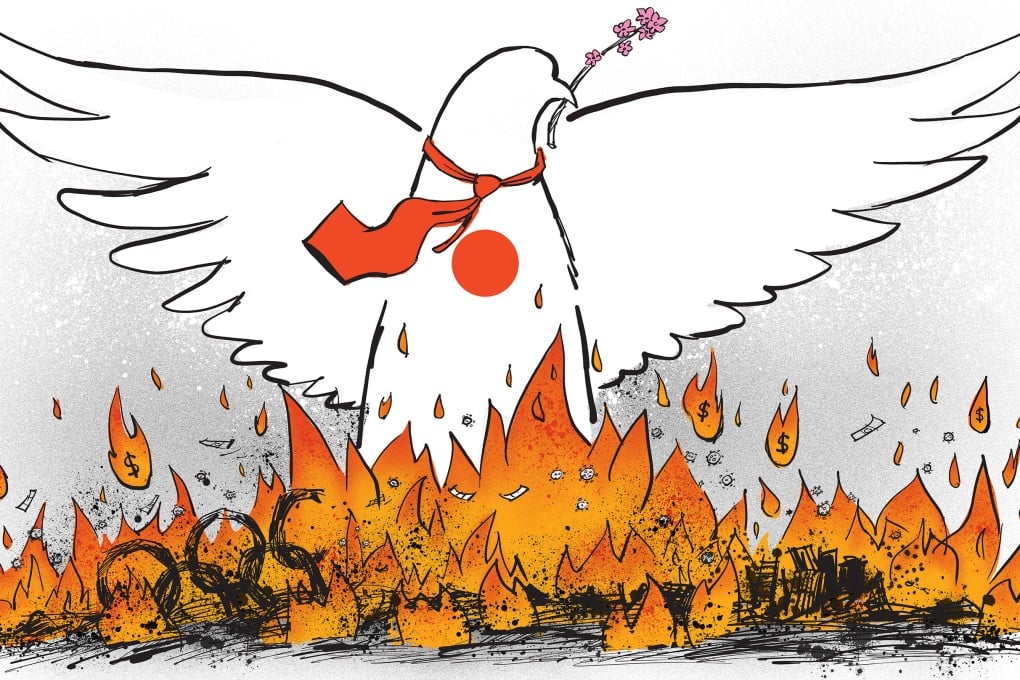

- Asia needs a progressive geo-economic evolution led by a friendlier, outward-looking Japan, not further remilitarisation

- Japan does best and offers neighbours its best when it keeps its military on a leash while unleashing its impressive entrepreneurial powers

There are always concerns about Japan, with its background of brilliant accomplishments and unforgettable aggression. Now that Japan is in the foreground again with the cheerless Olympics, who can be sure what is next?

By the 1980s, there were times when it seemed as if Japan could afford to buy almost anything anywhere. Across the East China Sea, not many Chinese seemed to have any money to buy much besides bags of rice.

Even though Japan’s economy is still the world’s third-largest, the sense of stasis is unsettling. Note the polished, centralised direction from Beijing and entrepreneurial decentralisation as China roars into the 21st century. In the economic regard, might Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party deserve less respect than China’s Communist Party?