Macroscope | Why fears over slowing global Covid-19 recovery are premature

- Setbacks in the recovery are always possible, and news on the Delta variant and Chinese economic momentum will need to be closely watched

- But looking at economic fundamentals, this time it seems likely that it is bond markets that have got carried away with a gloomy world view

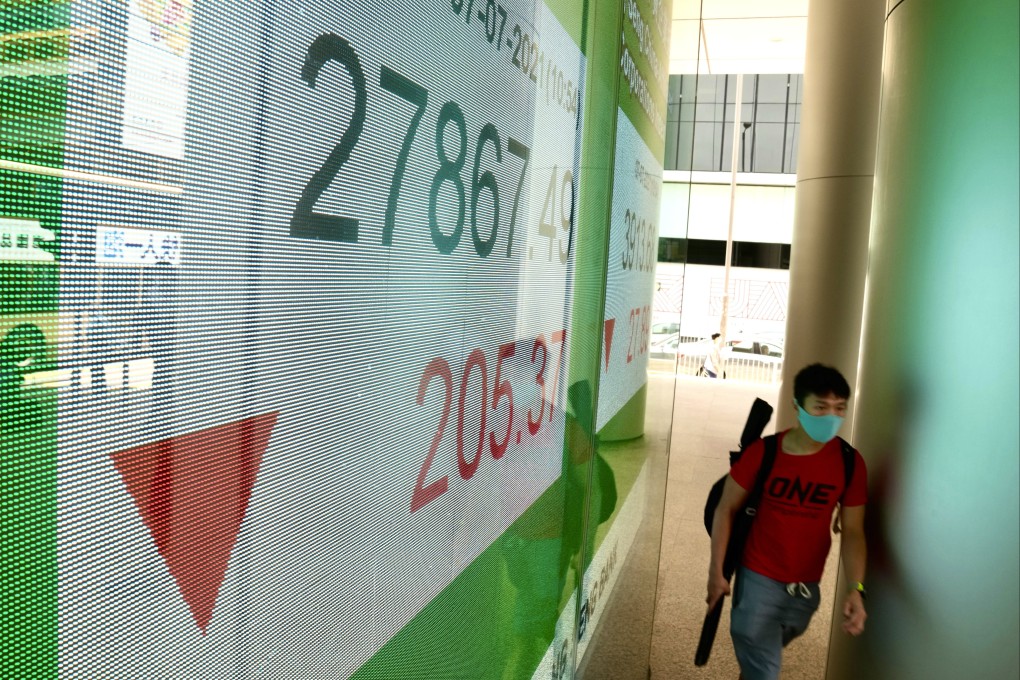

As we pass the halfway mark of 2021, investor worries about the growth outlook have once again begun to stir. The main trigger for this has been the recent fall in longer-term government bond yields, first and foremost in the United States but also in other parts of the world such as Europe and China.

The key global benchmark 10-year US Treasury interest rate plunged as low as 1.3 per cent last week from a high of 1.75 per cent at the end of March. Meanwhile, the Chinese 10-year government bond yield broke below 3 per cent for the first time in a year.

At first, the fall in bond yields was not necessarily bad news as it signalled fading concern that inflation might be more stubborn and persistent. However, this has broadened out into worries that global economic growth might not be as strong or long-lasting as had been expected.