Opinion | South China Sea: why report on Chinese boats dumping sewage doesn’t hold water

- The report concludes too much based on remote sensing, without confirming its findings with on-site observation

- The suggestion that damage to the coral threatens the food security of coastal states is based on unproven assumptions about the Spratlys as a genetic ‘savings bank’

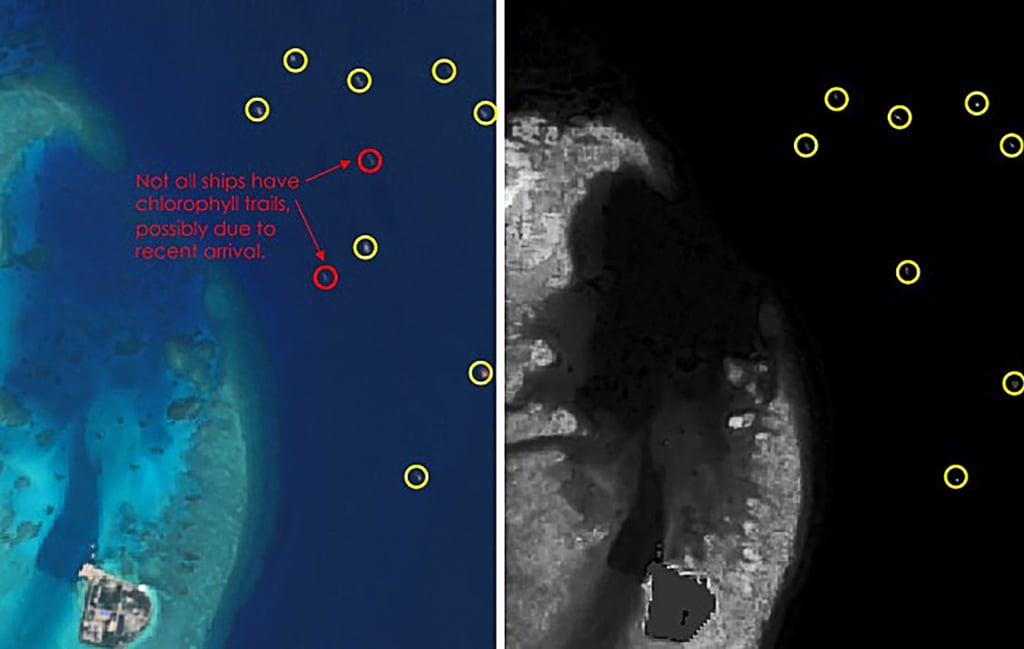

However, the allegations cry out for close examination. According to the report by US-based satellite spectral analysis firm Simularity, sewage from groups of anchored Chinese fishing boats in Philippine waters have caused algal blooms that damaged coral reefs and therefore endangered coastal states’ fisheries.

Liz Derr, a co-author of the study, said the team compared recent satellite images of the reefs with ones taken in 2016 and found a significant increase in areas that appeared white – those covered in chlorophyll-A – and a decrease in dark areas, which lacked chlorophyll.

Derr warned there could be a decline in fish stocks, an important regional food source, because schools of fish, including migratory tuna, breed in the affected reefs.

Philippine officials were sceptical. Referring to the report’s use of a 2014 photo from the Great Barrier Reef, Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin Jnr said the country “can’t and should not do foreign policy on the word of a liar in part who is likely a liar in whole. It is just not done.”