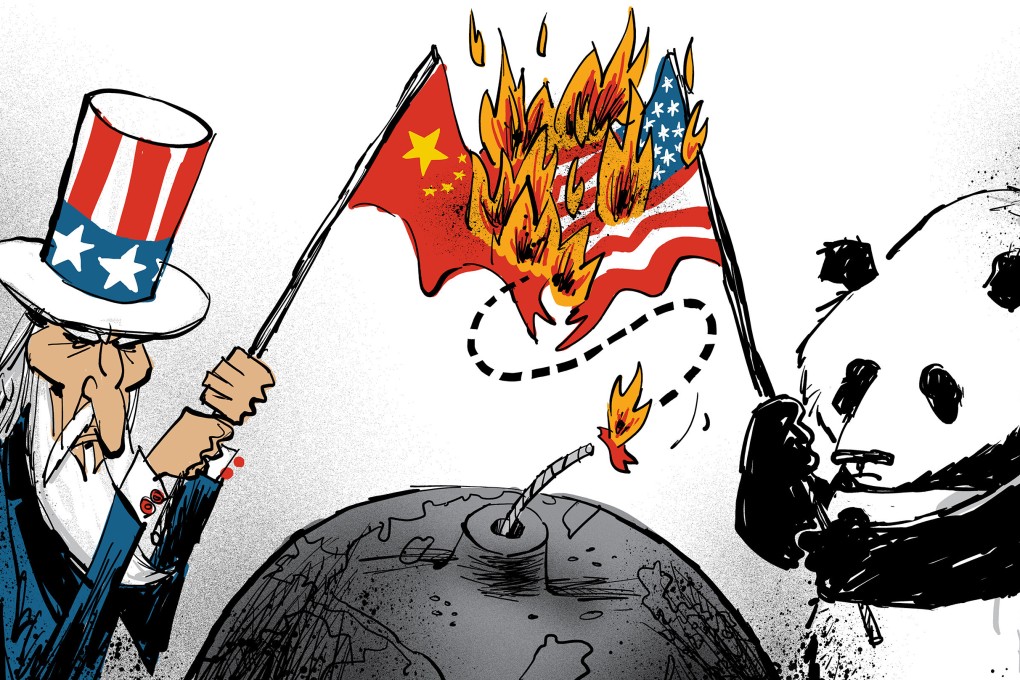

Opinion | Amid US-China brinkmanship, have relations reached the point of no return?

- There are three areas where unilateral action could trigger war – Taiwan, the East China Sea and South China Sea

- The danger in the South China Sea is that the red lines are ambiguous, leaving the US and China stuck in a circle of geopolitical and military gamesmanship

War may not be inevitable but it is increasingly likely. China and United States are on a collision course driven by competing ideologies, ambitions and visions of international order. Compromise and coexistence would require China to abandon some core interests or the US to accommodate some of them. Neither seems inclined to do so.

He says autocracies such as China and Russia bet their systems will outcompete democracies in addressing the enormous and increasingly complex challenges of the 21st century. He says they think democracies, with their Byzantine systems of checks and balances, will neither be efficient nor effective enough to meet these challenges and people’s expectations.

But the differences are more fundamental. The late Lee Kuan Yew hit the nail on the head: “For America to be displaced [ …] in the western Pacific, by an Asian people long despised and dismissed with contempt [ …] is emotionally very difficult to accept. The sense of cultural supremacy of the Americans will make this adjustment most difficult.”