South China Sea should top the list for US-China ‘guardrails’

- The road to agreement on this needed safeguard to prevent a clash will be long and tortuous, but worthwhile

- In particular, an agreement over incidents at sea similar to the US-Soviet pact reached during the Cold War should be pursued

According to US National Security Adviser Jake Sullivan, the US wants to “ensure that there are guardrails around the US-China competition”. However, he went on to say that the US and its partners want to “write the rules of the road for the 21st century in a way that advances our interests, reflects our values”.

The two countries could moderate the tone and tenor of their rhetoric.

The US probably has its own set of guardrails in mind, such as no attack or threat of the use of force against Taiwan; no attack or threats on its allies or their military assets; and, no interference with commercial navigation.

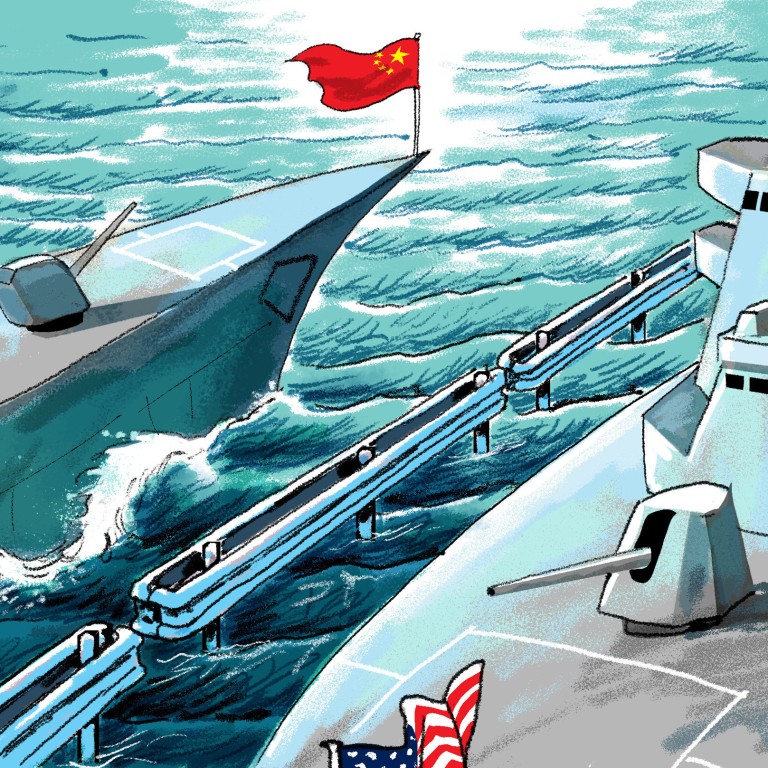

There is a particular need for guardrails for their interactions in the South China Sea, where their military forces come into frequent contact.

China would like to see a reduction, if not cessation, of what it considers threatening US behaviour like its close-in intelligence probes, freedom of navigation operations and provocative displays of power.

Thus, even if both can agree on mutual guardrails, they will probably disagree on definitions. For example, both say the other is behaving like a “bully” in the South China Sea. The US, and others, say China is bullying its rival claimants. But China thinks that US deployment of its most formidable symbol of power – its aircraft carrier strike groups – to the South China Sea is “bullying”. So bullying is in the eye of the bullied.

Then there is the more serious “threat of use of force”, which, according to the Law Insider site, means “a coercive attempt to compel another state to take or not take a certain specific action, or an action that is directed against the territorial integrity or political independence of that state”.

The US does not recognise China’s claims, while China thinks such operations are threatening its claimed territorial integrity. Perhaps this is why Biden reportedly assured Xi that the US would “stay outside of their territorial waters” for the time being.

Absence of face-to-face meetings with Xi puts Beijing’s ambitions in question

China’s body politic has become increasingly nationalistic and any public national loss of face and resultant loss of respect for its leadership could be a red line. This could include a confrontation involving military assets.

Thus, China may have an interest in an incidents-at-sea agreement with the US, similar to the one reached between the US and the Soviet Union in 1972, in the wake of several dangerous incidents between the US and Soviet navies.

The agreement provides for steps for warships to avoid collisions and includes prohibitions on interfering with each other’s “formations” and simulating attacks on the other party’s warships.

It also requires surveillance ships to maintain a safe distance from the object of investigation so as to avoid “embarrassing or endangering the ships under surveillance” and informing vessels when submarines are exercising near them.

It is time for the US and Chinese navies to consider an incidents-at-sea agreement. The two are adherents to the non-binding Code for Unplanned Encounters at Sea, reached at the 2014 Western Pacific Naval Symposium.

However, it has been ineffective in curbing incidents between the US and China, mainly because they do not stem from “unplanned” encounters. A higher-level bilateral agreement is needed.

They also say that US and Chinese interpretations of freedom of navigation are so different that they cannot be reconciled. Moreover, according to them, an incidents-at-sea agreement is a navy-to-navy agreement, but most Chinese “enforcement” activities are carried out by its coastguard and even civilian vessels.

There are also those who say China is not a responsible state actor and would violate any such agreement anyway. But all these objections can be mitigated by good faith on both sides.

Mark J. Valencia is an adjunct senior scholar at the National Institute for South China Sea Studies, Haikou, China